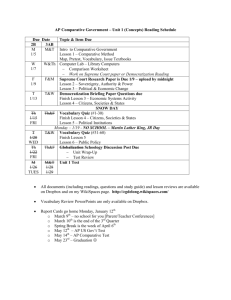

here - wcces

advertisement