Comparative Education - Higher Education Commission

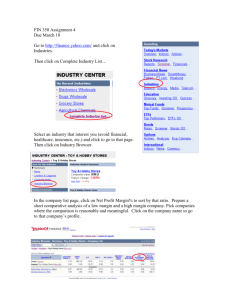

advertisement