Instructional Designer's Cheat Sheet

advertisement

Instructional Designer’s Cheat Sheet

Compiled by Suzanne Alexander, 2014

Contents

HPT Framework

3

Gilbert, Thomas

Leisurely Theorem 1: Worthy Performance

Leisurely Theorem 2: PIP (gap)

Leisurely Theorem 3: BEM

Why Chevalier’s version?

Chevalier-Gilbert Comparison

Leisurely Theorem 4: (Comprehensive) Value of Accomplishment

4

4

4

4

6

6

7

Harless’ Front End Analysis (FEA)

8

13 Smart Questions

Performance Analysis:

Cause Analysis:

Intervention Selection:

8

8

9

9

Kaufman’s Organizational Elements Model (OEM)

9

Mager & Pipe Performance Analysis

[1] What’s the problem?

[2] Is it worth solving?

[3] Can we apply fast fixes?

[4] Are consequences appropriate?

[5] Do they already know how?

[6] Are there more clues?

[7] Select and implement solutions:

10

10

10

10

10

10

10

10

Bronco ID Model

11

Task Analysis

Determine Level of Detail:

Qualify whether it’s a task:

Procedure

Exemplary, on-the-job performance

PARI tables

Tips

12

12

12

12

12

13

13

Mager-style Objectives

14

Performance Assessments

Performance Types:

Instrument Types:

Mastery Level

15

15

15

15

Merrill’s First Principles of Instruction

[1.0] Problem centered

[2.0] Activation

[3.0] Demonstration

[4.0] Application

[5.0] Integration

Other Instructional Design Models

16

16

16

16

17

17

17

Kirkpatrick Evaluations

19

Scriven’s KEC

Adapted Report Format

Use KEC (Scriven, 2003) as a framework – Chapter 10:

Part 1: Preliminaries

Part 2: Foundations

Part 3: Sub-evaluations

Part 4: Conclusions

20

20

20

20

21

21

22

Kellogg’s Program Logic Model

23

Impact/Evaluation Model Comparison

Scriven’s KEC

24

24

Chyung Evaluation Rubric: “How Good Is This Apple?”

Final Rubric:

Evidence-Based Practice

25

25

26

SCM (Success Case Method), Brinkerhoff

Ch-2: How the Success Case Method Works: Two Basic Steps

Relating the SCM to our Evaluation project:

Knowles Core Adult Learning Principles

26

26

27

28

Culture

28

Six-P Evaluation Framework (Marker)

29

HPT Framework

Gilbert, Thomas

Leisure = time + opportunity

“implies an opportunity for doing something different and better, and time available for doing

so.” – relates to human capital.

Behavior vs. Accomplishment – “Behavior you take (bring) with you; accomplishment you

leave behind.” (Gilbert) – Behavior is a verb, an accomplishment is a noun.

Behavior = pushing the vacuum around

Accomplishment = clean floors

Leisurely Theorem 1: Worthy Performance

Defines worthy performance (W) as the ratio of valuable accomplishments (A) to cost of

changing behavior (B).

W = A/B -or- W = A/(P+E)

The ratio is less than 1 when the cost (B) is greater than the value of accomplishment (A).

Theorem 3 states “B” = P (behavior) + E (environment).

Leisurely Theorem 2: PIP (gap)

PIP (Potential for Improving Performance) = Performance Gap

The gap between desired and current performance can be determined by comparing "the

very best instance of that performance with what is typical" (Gilbert, 1988, p.49). Exemplary

performance (Wex ) is demonstrated when behaviors result in the best outcomes. Typical

performance (Wt) is the current level of performance. The potential for improving

performance (PIP) is the ratio between the two and can be expressed as (right)

PIP = Wex/Wt

The PIP is the performance gap. The greater the gap, the greater the potential for typical

performers to improve their performance to the exemplary level. Rather than viewing this gap

as a problem, this model helps people see the potential for improvement more positively

(Chyung, 2002).

combine it with Joe Harless’ Front End Analysis (FEA).

Leisurely Theorem 3: BEM

Behavior Engineering Model.

Cause analysis – deficiency may be in environment (E), personal (P), or both, but ultimately a

“deficiency of the management system (M).

Components of behavior: Behavior (B) is equal to a person’s repertory of behavior (P)

modified by their supportive (working) environment (E).

B=P+E

BEM – Gilbert/Chevalier Comparison

Information

Instrumentation

GILBERT:

Environmental

Supports

Data

Do typical performers know

what they are expected to do?

• Does the individual know

what is expected of them?

• Do people know how well

they are performing?

• Are people given guidance

about their performance?

Do they have appropriate tools

to do their job?

• Are the tools and materials

of work designed

scientifically to match

human factors?

CHEVALIER:

Environment

Information

Resources

• Roles and performance

expectations are clearly

defined; employees are

given relevant and frequent

feedback about the

adequacy of performance.

• Clear and relevant guides

are used to describe the

work process.

• The performance mgmt.

system guides employee

performance and

development.

• Materials, tools, and time

needed to do the job are

present.

• Processes and procedures

are clearly defined and

enhance individual

performance if followed.

• Overall physical and

psychological work

environment contributes to

improved performance;

work conditions are safe,

clean, organized, and

conducive to performance.

GILBERT:

Repertory of

Behavior

Knowledge

Capacity

(what they bring

with them to the

job.)

CHEVALIER:

Individual

[1]

[1]

[4]

Instruments

Motivation

[2]

Knowledge/Skills

Capacity

[6]

BEM as a diagnostic tool: (*orange italic)

* Why are some no performing as well as others?

* What caused the PIP (gap)? How can I help reduce the gap?

* What would support employees in a worthy performance?

[6]

Are they motivated to perform

the job?

• Has a motivation

assessment been

performed?

• Are people willing to work

for the incentives?

• Are people recruited to

match the realities of the

job?

[5] Motives

• Employees have the

capacity to learn and do

what is needed to perform

successfully.

• Employees are recruited

and selected to match the

realities of the work

situation.

• Employees are free of

emotional limitations that

would interfere with their

performance.

[3]

• Financial and non-financial

incentives are present;

measurement and reward

systems reinforce positive

performance.

• Jobs are enriched to allow

for fulfillment of employee

needs.

• Overall work environment is

positive, where employees

believe they have an

opportunity to succeed;

career development

opportunities are present.

[5] Motives

Are they capable of

performing, or are they ready

to do the job?

• Do people have the aptitude

to do the job?

• Do people have the physical

ability to do the job?

• Flexible scheduling of p. to

match peak capacity.

[3]

Are they rewarded for doing a

good job?

• Are there adequate financial

incentives contingent upon

performance?

• Have Nonmonetary

incentives been made

available?

• Are Career-Development

opportunities available?

[2] Incentives

Do they have enough

knowledge to do their job?

• Do people have the skills

and knowledge needed to

perform as expected?

• Is well-designed training that

matches requirements of the

performance available?

• Employees have the

necessary knowledge,

experience and skills to do

the desired behaviors.

• Employees with the

necessary knowledge,

experience and skills are

properly placed to use and

share what they know.

• Employees are cross-trained

to understand each other’s

roles.

Incentives

[4]

• Motives of employees are

aligned with the work and

the work environment.

• Employees desire to

perform the required jobs.

• Employees are recruited

and selected to match the

realities of the work

situation

Why Chevalier’s version?

•

•

•

•

More comprehensive – suggests more questions to be asked

More scalable (?)

Terms adapted to reflect the way we typically speak about performance

More specific (Gilbert’s version seems more vague to me) which helps me to get down

to an underlying cause more efficiently and effectively.

Chevalier’s Order of analysis

According to Chevalier, environmental supports pose the greatest barriers to exemplary performance.

Environment

1. Information à

2. Resources à

3. Incentives à

Individual

6. Knowledge ß

5. Capacity ß

4. Motives ß

Gilbert’s Order of analysis

Environment

1. Information à

2. Resources à

3. Incentives à

Individual

4. Knowledge à

5. Capacity à

6. Motives à

According to Gilbert, "The behavioral engineering model serves one purpose only: It helps us to observe

behavior in an orderly fashion and to ask the 'obvious' questions (the ones we so often forget to ask) toward the

single end of improving human competence." (Gilbert, as cited in Van Tiem, Moseley, & Dessinger, 2012, p. 14).

Geary Rummler and Alan Brache,

“If you pit a good performer against a bad system, the system will win almost every time”

(Rummler & Brache, 1995, p. 13).

Chevalier-Gilbert Comparison, and Suzanne’s add-ons

Information/Data – both support investigation into whether expectations have been clearly

communicated, and if frequent performance-related feedback is present. Another dimension I

would add to this quadrant is whether the performance is an intrinsic requirement of the

subject’s overall performance. For example, it may be beneficial for an employee to know

something, but are they asked to apply it to the job?

Resources – if it’s environmental, and it’s not “info” and not “incentives”, then it typically gets

categorized under Resources. Chevalier hints at psychological supports under this category.

(Example of Stanford Hosp. vs. PAMF) This seems to be the context under which the job is

performed. Seems like there’s a lot more that would be contextual not included here – seems

somewhat incomplete. For instance, where would you categorize distractions in the work

environment that are adversely affecting performance?

Incentives – Chevalier drops the career development opportunities, but it’s one of the no. 1

reasons people leave their jobs. Perhaps it was dropped because it’s awkward categorized

as an “incentive”, but it is categorized correctly as an environmental-motivational issue under

Gilbert’s model. Overall job satisfaction, goals and direction should also be included here.

Note, too, that to be successful a person needs both drive and direction. How do you build

this into the job?

Motives – Gilbert’s model is vague and ambiguous, “assessment of people’s motives to

work”. Chevalier at least asks if the subject desires to do the job. It may suggest that an

individual might see the work as being beneath them. Both of these fall short of the

underlying worker motivation, “to improve their quality of life”. Money is part of that, but other

factors that promote a work-life balance may also be important. Other factors such as

prestige, the recognition of making a significant contribution, position and power may explain

certain behaviors pertaining to ego as it relates to their job and title.

Capacity – Chevalier focuses more on the subject’s physical and mental capabilities,

whereas Gilbert gives consideration to peak performance dynamics, the subject’s ability to

adapt, and social capacities. This quadrant seems vast, almost too vast to sum up succinctly

in a few bullet points. For instance, individual capacity is a dynamic factor relative to other

factors such as age, stress, physical wellbeing, family matters, etc. It also doesn’t consider a

subject’s unrealized capacity leading to frustration and underperformance.

Knowledge/Skills – This is the quadrant where training would be prescribed if a gap were

found; however, as a cause analysis, it should look at the underlying causes as opposed to

specific solutions or interventions. Yet, Gilbert’s model asks if training supports specific

performance. Chevalier’s model does a much better job asking if the subject has the requisite

knowledge or skills, and is more clear about what is meant by “placement” and matching

employee strengths with specific roles. Neither model asks Mager & Pipe’s quintessential

question, “Have they been able to do it before?” Van Tiem & Mosely propose some additional

questions here:

1.

Did the employee once know how to perform as desired?

2.

Has the employee forgotten how to perform as desired?

3.

Has the nature of the job changed, requiring an update?

4.

Is there just too much to know (i.e., the employee is on overload)?

5.

Does the workplace support the employee's knowledge and skills?

Based on Van Tiem, Moseley and Dessinger (2012), p. 168-176

** The Van Tiem, Moseley and Dessinger tool is very beneficial, but it had fallen off my radar by the

time I got to this project – too bad. (see VanTiem_Moseley_Dessinger_2012.docx)

Leisurely Theorem 4: (Comprehensive) Value of Accomplishment

The effects and side effects of behavior affect the overall value of the accomplishment, not

just the value of the single change in isolation. Diffusion of effects – maximize the overall

effects of interventions systemically – “there is no way to alter one condition of behavior

without having at least some effect on another aspect.”

__________________

References:

Gilbert, T. (2007). Human competence: Engineering worthy performance(Tribute edition). San Francisco, CA:

Pfeiffer.

Harless’ Front End Analysis (FEA)

Procedure that includes phases of:

* Performance analysis

* Cause analysis

* Intervention

Cycles through the ADDIE steps

Harless (1973) explains that the purpose of conducting a front-end analysis is to ask a series

of “smart questions” in order to prevent spending money on unnecessary activities, to come

up with the most appropriate solution(s), and to produce desired performance outcomes:

Front-end analysis is about money, first and foremost.

13 Smart Questions

Performance Analysis:

1. "Do we have a problem?" (What are the indicators and symptoms?)

- Monitor performance data baseline.

- List of indicators, symptoms of problems.

- Describe performance tasks that may be deficient.

2. "Is it a performance problem?" (Do the indicators show that human performance is

involved?)

- Hypothesis of nonperformance cause of the problem.

- Test of hypothesis.

- Observation of mastery performance.

3. "How will we know when problem is solved?" (What is mastery performance?)

- Description of mastery performance to task level of specificity.

- Description of problem-level goals.

4. "What is the performance problem?"

- More detailed description of mastery performance.

- More detailed description or actual performance.

- Comparison of mastery to actual.

5. Should we allocate resources to solve the problem?

(What is the value of solving the problem vs. some other?)

Cause Analysis:

6. What are the possible causes of the problem?

7. What evidence bears on each hypothesis?

8. What is the probable cause?

Intervention Selection:

9. What general solution type is indicated?

10. What are the alternate subclasses of solution?

11. What are the cost/effects/development time of each?

12. What are the constraints?

13. What are the goals of the project?

Kaufman’s Organizational Elements Model (OEM)

Kaufman and his colleagues proposed the

•

OEM uses a systemic approach to look at gaps in performance.

•

Purpose: separate the means from the ends during needs assessment.

•

5 system elements:

inputs and processes (means or organizational efforts)

products, outputs, and outcomes (the ends, results, and societal impacts).

•

3 result levels of each system: micro, macro, and mega - OEM helps us assess our

needs at each level

•

Needs represent a gap in results, rather than a gap in the means -- in order to arrive

at an effective intervention

Mager & Pipe Performance Analysis

The seven stages are part of a flow diagram and each phase is entered sequentially only

after the prior stage has been cleared:

[1] What’s the problem?

•

Whose performance is concerning you?

- describe discrepancy

[2] Is it worth solving?

à If not worth pursuing – stop here.

[3] Can we apply fast fixes?

•

•

•

•

Are the expectations clear? – if not, clarify expectations.

Are there adequate resources? – if not, provide resources

Is the performance quality visible? – if not, provide feedback

If this solves the problem – stop here.

[4] Are consequences appropriate?

•

•

•

Is the desired performance punishing? – if so, remove punishment

Is poor performance rewarding? – if so, remove rewards

Are performance consequences used effectively? – if not, adjust consequences

à If this solves the problem – stop here.

[5] Do they already know how?

Is there a genuine skill deficiency?

- have they done it successfully in the past?

- if so, is it used often? – if so, provide feedback – if not, provide practice

[6] Are there more clues?

Can the task be made easier? – if so, simplify the task

Are there any other obstacles? – if so, remove obstacles

Does the person have the potential to change? – if so, provide training – if not, replace the

person

[7] Select and implement solutions:

If training is called for:

1) calculate costs à 2) select best solutions à 3) draft action plan à 4) implement & monitor

Bronco ID Model

Analysis Phase:

[1] Performance & Cause Analysis

[2] Learner Analysis

[3] Task Analysis

Design Phase:

[4] Instructional Objectives

[5] Performance Assessment

[6] Instructional Plan

Development Phase:

[7] Instructional Materials

Implementation Phase: (deliver the course)

Evaluation Phase:

[8] Formative Evaluations – Example, Kirkpatrick evaluation levels 1 and 2 to identify learner

reactions to the instruction, and to gather data relating to improved skills in applying the learning

objectives.

Task Analysis

Determine Level of Detail:

•

•

•

•

•

A job – (collection of responsibilities and tasks)

Broad responsibilities

Tasks

Activities

Steps (discrete actions)

Qualify whether it’s a task:

q

q

q

q

Response to a work assignment?

Specific beginning and ending?

Result in a meaningful product?

The activity is/should be required?

If the answer to the four criteria is yes, then it qualifies as a task.

Procedure

McCampbell (n.d.) describes the following four steps for developing a procedural task analysis:

1.

2.

3.

4.

List the main steps

Fill in the detail of the main steps

Check the task analysis for correctness

Check the task analysis for level of detail

Exemplary, on-the-job performance

One thing to keep in mind is that a task analysis should describe exemplary on-the-job

performance of the task. The best way to do this is to observe and talk to an expert performer

– someone who actually performs the task in an exemplary way. Avoid a situation in which

you rely only on manufacturer’s manuals, organizational standard operating procedures

(SOPs) or other written documents. They don’t always accurately describe the way real

experts perform a particular task on the job. (Expert performers) are likely to know short-cuts,

work-arounds, “tricks-of-the-trade,” and other variations that aren’t in the manual.

Because it describes exemplary performance, task analysis will often involve working with a

subject matter expert (SME). (Note: some SME consultants are not performers. Interview an

exemplary performer, not just the consulting SME.) If you’re working with a SME, remember

that this is a partnership. Your job is to obtain a clear, complete analysis by helping the SME

articulate the tasks required to perform the job. The SME’s job is to provide accurate

information and suggest where your analysis may be incomplete or inaccurate. Working with

SMEs can be tricky. Because of their experience and expertise, they typically do things

automatically, without much explicit thought. So they aren’t always very good at describing

what they do or know, or very patient with people who aren’t SMEs. Your challenge will be to

probe and explore so that you get a clear, complete picture of what’s required to perform the

selected tasks. … “dumb” questions can help you identify the details of the task in a way that

other novices (the learners for your instruction) are likely to understand.

PARI tables

Other decisions are more complex in nature. This happens when people solve problems on

the job. Instead of simple if/then logic (often called algorithms), these decisions are more

complex, involving consideration of multiple factors (often called heuristics). To document a

complex decision, use a table like this (sometimes called a “PARI table”):

Precursor

Action

Results

Interpretation

•

•

•

•

The order in which you fill in these parts doesn’t matter. But it’s often easiest to start with

precursor, followed by the results, then the interpretation, and finally the action.

•

•

•

•

Precursor (Inputs) = what prompts you to perform the task. This can also include what is given

when you begin the task. Think of inputs as stimuli and resources.

Action (Process) = any activities that you complete in performing the task.

Results (Outputs) = what happens (or should happen) when you perform the task?

Interpretation (Decision rule) = questions or ideas that help you perform the task.

Tips

•

Choose action verbs that concisely describe the behavior. Use words that say what you mean and

mean what you say.

•

Odds are that procedural task analysis will become the basis for a job aid that you use in the

instruction. That means you’ll want to write your task analysis in a way that you can easily convert

it into a job aid.

•

Separate information about the task, hints about performing the task, and cautions about the task

from the task statement itself.

You may want to use a set of custom icons. For example:

' Hot tip: Hints or advice about performing the task.

F Note: Additional information.

M Caution: Use for safety and potential mistakes.

Use a consistent scheme to number each element in your task analysis. There are many

ways to do this. One common way is to use a series of indents and .numbers to indicate

tasks, activities, and steps. This would look something like this:

3.0 [task]

3.1 [component activity of 3.0]

3.1.1 [component step of 3.1]

3.1.2 [component step of 3.1]

3.1.2.1 [component substep of 3.1.2]

3.1.2.2 [component substep of 3.1.2]

3.2 [component activity of 3.0]

4.0 [task]

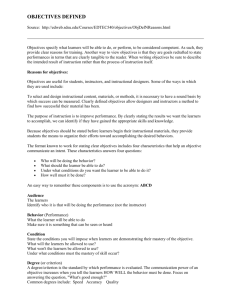

Mager-style Objectives

Performance:

What the learner will do on-the-job. Note that this component should

describe observable behaviors - what you want the learner to do on-the-job.

Avoid vague terms like understand, appreciate, and know.

Conditions:

The on-the-job circumstances under which the learners will be expected to

do the specified behavior. Note that the conditions should describe the

circumstances and resources that will be available at the time the behavior

is performed. Avoid references such as following the instruction because

they don't describe the conditions that will exist at the time the behavior is

performed. In addition, the conditions should describe the real-world

situation rather than the classroom situation. What will the circumstances be

when the learner does the expected behavior back in their job setting

(whatever that is) rather than in the instructional environment. Avoid

references such as within a role-play exercise because they describe the

training conditions instead of the real-world conditions.

Criteria:

The standard that defines acceptable performance of the behavior on-thejob. Note the difference between criterion and mastery level. A criterion

describes what is acceptable for each performance of the behavior. In

contrast, a mastery level describes how many times the learner must

perform the behavior to "pass." Avoid references such as . . . 2 out of 3

times or 80% of the time. These describe a mastery level, but not a criterion.

The mastery level is a question for the assessment instrument, rather than

the objectives.

There are a number of different ways to define a correct performance. Of course, not all of these

categories will apply to every objective. The following table describes a variety of criteria that could

apply to an objective.

Duration

Time

Rate

Accuracy

Number of

errors

Tolerances

Essential

characteristics

Quality

Specifies the required length of the performance.

Example: Paramedics will maintain a steady CPR rate for at least 10 minutes.

Specifies the speed at which the performance must take place.

Example: Court reporters will record at a rate of 150 words per minute.

Specifies the maximum number of errors allowed.

Example: Flight attendants will announce preflight boarding instructions with no more

than two verbal errors.

Specifies the maximum range of measurement that is acceptable.

Example: Quality assurance analysts will calculate a mean to the nearest .01.

Specifies the features or characteristics that must be present in the

performance.

Example: Salespersons will employ a sales approach that is consultative and

identifies customer needs.

Source

Specifies the documents or materials that will be used to judge the

performance.

Consequences

Specifies the expected results or the performance.

Example: Graphic designers will create a series of computer screens that are

consistent with established principles of screen design.

Example: Managers will be able to develop a response to an employee conflict that

reduces the company’s legal liability.

Carliner makes the point that objectives are derived directly from a task analysis (page

68). The important point here is that the completed objectives and the completed task

analysis should be aligned. If something is identified as an intended outcome (objective) of

the instruction, it should be included in the task analysis. And if something is identified as a

major component of the task analysis, it should be associated with an intended learning

outcome (objective). You can complete the task analysis first, write the objectives first, or

complete them concurrently. Either way, when they're finished, they should line up.

Pay close attention to this on-the-job focus. Building this into your objectives will be more

difficult than you might think.

Performance Assessments

There are 2 basic types of performances to assess – product

and process. In addition, there are 2 basic types of assessment

instruments – checklist and rating scale.

Product

Process

Checklist

Rating Scale

Performance Types:

•

Product assessment – This is useful when the learner’s performance results in something tangible

that can be evaluated. Examples include situations in which the learners have produced a widget,

architectural blueprint, or marketing plan. Notice that in each of these examples, the primary

focus is on a tangible product. We don’t have to watch the learners doing the task. We can

evaluate the finished product.

•

Process assessment – This is useful when the learner’s performance does not result in something

tangible. Examples include situations in which the learners give a presentation, coach an

employee, or perform a dance routine. Notice that in each of these examples, there is no

finished product. In order to evaluate the learner’s performance, we must watch it while it is

occurring.

Instrument Types:

•

Checklist – Both product and process can be evaluated using a checklist. A checklist lists each

assessment item and whether or not the learner met the criteria. It may also include observations

or comments.

•

Rating Scale – A scale (such as a Likert scale) defined by observable criteria. Example:

1 = gasping for air, dizzy; 2 = winded & tired/sleepy; 3 = tired, but could go for a walk… (etc.)

Mastery Level

An important distinction here is between criterion and mastery level. Criterion refers to the standard

(what qualifies as a correct response) for each time the task in that objective is performed. Mastery

level refers to (ratio of correct responses) how many times the learner must perform the behavior to

the established criterion to be judged successful. The basic question to ask when determining a

mastery level is – how many times must learners do ABC in order to convince you that they have

mastered that task?

Carliner, Cht. 4, Training Design Basics

Merrill’s First Principles of Instruction

[1.0] Problem centered:

Learning is promoted when learners are engaged in solving real-world problems.

Show task:

Learning is promoted when learners are shown the task that they

will be able to do or the problem they will be able to solve as a

result of completing a module or course.

Task level:

Learning is promoted when learners are engaged at the problem

or task level, not just the operation or action level.

Problem progression:

Learning is promoted when learners solve a progression of

problems that are explicitly compared to one another.

[2.0] Activation:

Learning is promoted when relevant previous experience is activated.

Previous experience:

New experience:

Structure:

Learning is promoted when learners are directed to recall, relate,

describe, or apply knowledge from relevant past experience that

can be used as a foundation for the new knowledge.

Learning is promoted when learners are provided relevant

experience that can be used as a foundation for the new

knowledge.

Learning is promoted when learners are provided or encouraged

to recall a structure that can be used to organize the new

knowledge.

[3.0] Demonstration:

Learning is promoted when the instruction demonstrates what is to be learned rather than

merely telling information about what is to be learned.

Consistency with learning goal:

Learning is promoted when the demonstration is consistent with

the learning goal:

(a) examples and non-examples for concepts,

(b) demonstrations for procedures,

(c) visualizations for processes, and

(d) modeling for behavior.

Learner guidance:

Learning is promoted when learners are provided appropriate learner

guidance including some of the following:

(a) learners are directed to relevant information,

(b) multiple representations are used for the demonstrations, or

(c) multiple demonstrations are explicitly compared.

Relevant media:

Learning is promoted when media play a relevant instructional

role and multiple forms of media do not compete for the attention

of the learner.

[4.0] Application:

Learning is promoted when learners are required to use their new knowledge or skill to solve

problems. This is about practice exercises that allow learners to construct the skills and

knowledge they need to pass assessments that indicate they can perform job tasks.

Practice consistency:

Learning is promoted when the application (practice) and the

posttest are consistent with the stated or implied objectives: (a)

information-about practice – recall or recognize information, (b)

parts-of practice – locate, and name or describe each part, (c)

kinds-of practice – identify new examples of each kind, (d) how-to

practice – do the procedure and (e) what-happens practice –

predict a consequence of a process given conditions, or find

faulted conditions given an unexpected consequence.

Diminishing coaching:

Learning is promoted when learners are guided in their problem

solving by appropriate feedback and coaching, including error

detection and correction, and when this coaching is gradually

withdrawn. Immediate feedback in early practice exercises gives

way to delayed feedback that learners receive after completing an

assessment.

Varied problems:

Learning is promoted when learners are required to solve a

sequence of varied problems.

[5.0] Integration:

Learning is promoted when learners are encouraged to integrate (transfer) the new

knowledge or skill into their everyday lives.

Watch me:

Learning is promoted when learners are given an opportunity to

publicly demonstrate their new knowledge or skill.

Reflection:

Learning is promoted when learners can reflect on, discuss, and

defend their new knowledge or skill.

Creation:

Learning is promoted when learners can create, invent, and

explore new and personal ways to use their new knowledge or

skill.

Other Instructional Design Models

Is Merrill's "First Principles" the Only Model For an Instructional Plan?

The short answer is "no." Over the years (actually centuries) smart people have developed a

variety of instructional models. For example:

The followers of Johann Herbart (an 18th century German philosopher) developed a 5-step

teaching method (Clark, 1999):

1. Prepare the pupils to be ready for the new lesson

2. Present the new lesson

3. Associate the new lesson with ideas studied earlier

4. Use examples to illustrate the lesson's major points

5. Test pupils to ensure they had learned the new lesson

Carkhuff and Fisher (1984) used the acronym "ROPES" to describe 5 essential components

for an instructional unit:

R -- Review: Assess the learner's existing knowledge

O -- Overview: Including the importance of the new information

P -- Presentation: Present new information and guide learning

E -- Exercise: Provide opportunities for practice

S -- Summary: Assess the level of learning

Gagne (1985) described 9 events of instruction:

Introduce the subject

1. Gain attention

2. Inform learners of the objectives

3. Stimulate recall of prior learning

Conduct the Learning Experience

4. Present the stimulus

5. Provide learning guidance

6. Elicit performance

Review & Enhance Retention

7. Provide feedback

8. Assess performance

9. Enhance retention and transfer – further application

Yelon (1996) described 5 types of student learning activities:

1. Motivation activities -- create interest in learning

2. Information activities -- help students acquire and recall ideas

3. Application activities -- provide opportunities for practice

4. Evaluation activities -- help students reflect on their learning

5. (?)

Merrill (2002) described 5 principles of instruction:

1. Problem

2. Activation

3. Demonstration

4. Application

5. Integration

It should be relatively easy to see a number of similarities among these instructional models.

You read Merrill's article for week 2 and the information in "ID Foundations 2: ID and learning

theory" applies here.

Kirkpatrick Evaluations

Level 1: Reaction. This is a measure of how participants feel about the various aspects

of a training program, including the topic, speaker, schedule, and so forth. Reaction is

basically a measure of customer satisfaction. It's important because management often

makes decisions about training based on participants' comments. Asking for participants'

reactions tells them, "We're trying to help you become more effective, so we need to know

whether we're helping you."

Another reason for measuring reaction is to ensure that participants are motivated and

interested in learning. If they don't like a program, there's little chance that they'll put forth

an effort to learn.

Level 2: Learning. This is a measure of the knowledge acquired, skills improved, or

attitudes changed due to training. Generally, a training course accomplishes one or more

of those three things. Some programs aim to improve trainees' knowledge of concepts,

principles, or techniques. Others aim to teach new skills or improve old ones. And some

programs, such as those on diversity, try to change attitudes.

Level 3: Behavior. This is a measure of the extent to which participants change their onthe-job behavior because of training. It's commonly referred to as transfer of training.

Level 4: Results. This is a measure of the final results that occur due to training,

including increased sales, higher productivity, bigger profits, reduced costs, less

employee turnover, and improved quality.

Scriven’s KEC

Adapted Report Format

Use KEC (Scriven, 2003) as a framework – Chapter 10:

Evaluation is “the determination of merit, worth, or significance” of something (Scriven, 2007).

By contrast with goal-based (or manager-oriented) evaluation, consumer- oriented evaluation

(aka needs-based evaluation) is conducted to determine the program’s merit, worth, or

significance by relating the program effects to the relevant needs of the impacted population

(Scriven, 1991).

Part 1: Preliminaries

(1) Exec Summary (1-2 pages)

•

•

•

short program description, context and big picture eval questions

(see Ch. 02) s/b ¼ to ½ page with bullet points (skimmable).

Give a hypothetical graphical profile with 5-9 dimensions and their relative importance (Ch. 07)

– to show what it would look like.

Describe briefly what mix of evidence should lead the evaluation team to draw an overall

conclusion about the evaluand as being excellent vs. acceptable vs. poor.

(2) Preface

•

•

•

who asked for the evaluation and why?

what are the main big-picture evaluation questions? Purpose (see ch. 2) – to determine

absolute or relative quality or value. Do not just pick one of these. Instead, explain how you

came to the conclusion that this was the main question.

Formative / summative / both?

•

Who are the main audiences for the report (2-3 key stakeholder groups, no everyone who

might be interested)

(3) Methodology

•

what methodology was used for the design and rational (JUSTIFICATION) for these choices

(experimental vs. case study; goal-oriented vs. goal-free; participatory vs. independent)?

Part 2: Foundations

(1) Background & Context

Provide just enough info to communicate the basic rationale for the program and context that

constrains or enables its performance:

•

•

•

Why did this program come into existence in the first place? Who saw the initial need for it?

(compare this later with the assessed needs found under the values checkpoint.)

How is the program supposed to address the original need, problem, or issue? What was the

purpose of the program’s original designers? (Links to process evaluation and outcome

evaluation. )

What aspects of the program’s context constrain of facilitate its potential to operate effectively?

(e.g. physical, economic, political, legal, structural) Feeds into the process evaluation

checkpoint.

(2) Descriptions & Definitions

•

•

Describe the evaluand in detail (for those unfamiliar with it) – what it is and what it does – not

just what it’s supposed to be. (This contrasts with what the program designers intended to

show what it’s really doing, but don’t have to mention.)

Include the logic model.

(3) Consumers / Stakeholders

•

•

Identify consumers and impactees

- demographics, geographic, downstream impactees

Links to outcomes (what happens to the impactees as a result of the program)

(4) Resources

•

•

•

•

Resource availability and constrains? (to interpret achievements & disappointments fairly.)

What could have been used, but wasn’t?

Areas where important resources were needed but not available?

Considerations: funds/budget; space; expertise; community networks

(5) Values / Dimensions

•

•

•

•

•

what should be considered valuable or high quality for the evaluand.

Briefly summarize needs assessment or other sources you used to define value. (See list in

ch. 6 – explain which sources were relevant and how they applied.)

Were any values in conflict?

How good is good, and what is most important? Justify the choices.

à Importance Weighting

How you arrived at the list of dimensions used in step 6 (process evaluation).

Part 3: Sub-evaluations

(6) Process Evaluation ß product of the program (my interpretation)

•

•

Evaluate the content and implementation of an evaluand.

List the main dimensions of merit that apply.

•

•

•

•

•

•

Relative importance of each criterion

Define any minimum levels of acceptable performance.

Clarify how importance was determined – add details in an appendix regarding strategies you

used (see ch. 7)

Use each dimension to rate the evaluand (excellent, very good, adequate, etc.)

For each rating, show what standards you used in a rubric

Cite what evidence led you to assign the rating (see ch. 8) ß or use a short summary with just

the ratings and brief explanation. THIS IS A PROPOSAL, not an actual evaluation.

Overall…

•

•

•

Evaluand content and implementation (see ch. 4)

Apply the values to the evaluand

Possible values include: ethics (equity & fairness), consistency w/ scientific standards,

efficiency, needs of consumers, needs of staff

(7) Outcome Evaluation ß Impacts of the program (my interpretation)

“Outcomes are all of the things that have happened to the consumers as a result of coming into

contact with the evaluand.”

•

•

•

•

•

Include effects on all important impactees

Include intended and unintended effects

Include short-term and long-term effects (if info available)

Rate the key outcome dimensions based on stated values from merit rubric (based on needs

assessment). Do not just report outcomes.

TIP: start with the main outcome dimensions and how the list was generated, then rate each

dimension on importance and how importance was established. Next, assign a quality or value

rating on each outcome dimension (see ch. 8). Lastly, explain the standards used (provide a

rubric) and the evidence that led to each rating.

(8&9) Comparative Cost-Effectiveness

•

list of comparisons relative to assigned resources (see ch. 4) –

{minimal, option a little more streamlined, (ACTUAL?), option with a little more, ideal}

(10) Exportability

•

value or could be applied outside its current context.

Part 4: Conclusions

(11) Overall Significance

Summary and synthesis of all the evaluative elements (see ch. 9)

•

•

•

performance on 5-9 major dimensions or components

overall conclusion about the evaluand’s quality or value.

Summarize the main strengths & weaknesses – which ones are most important and why?

(12) Recommendations & Explanations

Kellogg’s Program Logic Model

The basic logic model:

Impact/Evaluation Model Comparison

Model:

Brinkerhoff

SCM

Program

Capabilities

Critical Actions

Key Results

Business Goals

Kirkpatrick

4-Levels

L1 Reaction

L2 Learning

L3 Behavior

Change

L4 Results

Kaufman’s

OEM

Means: Inputs &

Processes

Micro-level

Products

Macro-level

Outputs

Mega-level

Outcomes

Kellogg’s

Logic Model

Resource

Activities

Outputs

Outcomes

Impact

Scriven’s KEC

Consumer-Oriented Evaluation - Evaluation is “the determination of merit, worth, or

significance” of something (Scriven, 2007). By contrast with goal-based (or manageroriented) evaluation, consumer- oriented evaluation (aka needs-based evaluation) is

conducted to determine the program’s merit, worth, or significance by relating the program

effects to the relevant needs of the impacted population (Scriven, 1991). Scriven’s (2007) key

evaluation checklist (KEC), developed in 1971 and refined many times since then, assists in

professional designing, managing, and evaluating of programs, projects, plans, processes,

and policies.

Chyung Evaluation Rubric: “How Good Is This Apple?”

[1] Product to be evaluated (evaluand) –

[2] Purpose of the product – (why is it important – from impact analysis)

[3] Evaluation question to be answered – (product and/or impact – how good is it?)

[4] Decision to be made – “Would you buy/recommend it?”

Establishing

Evaluative Criteria

(Dimensions)

Determining

Importance

Weighting

Constructing

Standards/Rubrics

Measuring

Performance

Against

Standards/Rubrics

Synthesizing &

Integrating

Evidence into

Final Conclusion

What are the criteria

(dimensions) on

which the product

should be judged

(e.g., texture, color,

aroma, calories)?

List several criteria.

Which criteria are

more important than

others? Which scale

would you use (e.g.,

1.important, 2.very

important,

3.critical)?

Determine relative

importance among

the criteria, using

your scale.

How well should it

perform on each of

the dimensions

(What are your

standards)?

Develop a rating

rubric with 3-4

levels of

descriptions (e.g.,

1.No thank you,

2.OK, 3.Awesome)

Now, actually

measure the quality!

Factoring the

importance

weighting into

measured

performance

results, how would

you rate the overall

quality of the

product? How good

is it? Use the 3point final rubric

(1.Poor, 2.Good,

*

3.Excellent).

3. Critical

1. No thank you –

bitter, tart

Mostly sweet but

it’s got just a little

bit of tart taste =

2. OK

A. Taste

2. OK –

Sweet & tart

For each criterion,

how well does it

measure up against

the standards/

rubrics you have

set?

3. Awesome –

Really sweet!

B. Size

1. Important

1. No thank you –

smaller than my fist

2. OK – about my fist

Larger than my fist

=

3. Awesome

C. Organic

2. Very important

2. OK –Natural

[Critical = OK]

+

[Important = Awesome]

+

[Very important = No

thank you]

è Therefore,

3. Awesome – larger

than my fist

1. No thank you –

non organic/natural

Overall,

how good is it?

Nonorganic/natural

=

1. No thank you

3. Awesome –

Organic

“Poor”

On a 3-point

scale*:

Poor – Good –

Excellent

Final Rubric:

Poor: If at least one dimension = No thank you

Good: If ‘Critical’ dimension = OK; other dimensions = OK or Awesome

Excellent: If ‘Critical’ dimension = Awesome; other dimensions = OK or Awesome

Decision: (I would buy/recommend it if it is Good or Excellent)

[ ] Yes, I would buy/recommend the apple.

[x] No, I would not buy/recommend the apple.

Evidence-Based Practice

I see two levels of Evidence Based Practice at play here. The first level is - do we as HP

practitioners use evidence based tools and processes as we diagnose a performance

problem and provide recommendations for interventions.

The second level of EBP is the content itself. We generally do use Subject Matter Experts for

the content, but the content should also be EBP. That can be obtained by observing

exemplary performers, consulting industry standards, the literature or best practices. Just

"making it up" doesn't quite cut it for me. Garbage in, garbage out. How do we know what he

recommended is the best practice?

I'll share an example: I created a job aid for managers to show them how to run financial

reports. A needs analysis revealed only 25% of managers at a particular hospital knew how

to run the reports needed to manage their budget. My first run at creating the job aid was to

try it myself and document each step. Then I consulted an SME, an exemplary performer

and a front-line user to assure the end product was correct, the most streamlined process

and also understandable from an end-user standpoint. Using end-users can be part of a pilot

to test usability.

SCM (Success Case Method), Brinkerhoff

The success case method

See “Telling Training’s Story” by Brinkerhoff (on Kindle)

•

•

•

Ch-2: How the Success Case Method Works: Two Basic Steps

Ch-3 Success Case Method Strategy – Building Org. Learning Capacity

Ch-4 Focusing and Planning a Success Case Method Study

Ch-2: How the Success Case Method Works: Two Basic Steps

Applied to training evaluation.

Step 1:

Identify the most and least successful;

Collect data documenting each.

Step 2:

Interview from both groups – understand, analyze, and document their stories.

Answer the question: Has anyone used the training to achieve worthwhile results?

IF we cannot find anyone at all who has done anything remotely worthwhile with his or

her training, then of course we have learned something valuable; discouraging, yest,

but valuable, because we now know that something is very wrong and that the training

is having not apparent impact.

Most and least successful learners often share factors in common – for instance, level of

support from boss may result in dichotomy between most- and least-successful.

REALITY 1: Training typically results in a performance bell-curve. Training programs

produce very reliable (reproducible) results: some have used their learning to get great

results; some have not used their learning at all. Most participants attempt, fail, and revert

back to what they did before.

LOW PERFORMERS à

ß TOP PERFORMERS

There are usually some who find a way to put training to use in valuable ways. …Leveraging

the knowledge gained from the few most successful trainees to help more trainees achieve

similar levels of success is a key goal of a SCM study.

REALITY 2: Training alone never works. Non-training factors enable and encumber trainees.

(“Pit a good worker against a bad system, and the system will win every time.” -Rummler)

Examples –

[Environmental:] managerial support, incentives, opportunities to implement what was

learned

[Instructional:] timing of training, flawed instructional design, poor instructor, ineffective

delivery, limited opportunities to practice, poorly designed materials, wrong target group

attending training, trainees inadequately prepared, etc.

Surveys – Tend to be unproductive because surveys of learning application produce

discouraging results, showing …that most trainees have not applied or sustained use of their

learning in sustained performance. There is little that a typical training department can do,

since changing the training program will not do much to create better results.

Relating the SCM to our Evaluation project:

(!) The SCM method would have changed how we collected data, and what data we were

attempting to document.

Our survey results were in fact very disappointing, especially to the program manager. All we

learned is that the program is under-performing. What we didn’t find out is if anyone was able

to achieve the desired performance level and what they did that might have overcome certain

unidentified challenges. We likewise did not identify any environmental factors that might

have presented a road-block for many in achieving the desired performance. As a formative

evaluation that meant that we did not present more constructive recommendations to the

client organization.

One inherent challenge is that you must identify certain performers as low-performers which

may be potentially harmful to them or their job.

The other challenge may be some length of time required following the training in order to

identify the effects of the training.

Citation

Brinkerhoff, R. (2006). Telling training’s story: evaluation made simple, credible, and effective. San Francisco :

Berrett-Koehler

Knowles Core Adult Learning Principles

Andragogy

Pedagogy

1. The need to know

(relevance)

Learners need to know why

and how what they will learn

will apply to their lives.

Learners need to know what

they must learn.

2. Self-concept

Learners are autonomous, selfdirected, and make their own

decisions about what they need

to learn.

Learner is dependent on

instructional authority.

3. Experience

Learners posses experience and

prior knowledge. They actively

participate in acquiring and

adapting the content.

Learner has little relevant

experience of their own and

relies on that of the expert.

They receive content through

transmission.

4. Readiness

Learners’ readiness is based on

a life-based need.

Learners’ readiness is based on

promotion and certification.

5. Orientation to

learning

Learners approach learning

from a goal-oriented or

problem-centered perspective.

Learners approach learning

from a subject-oriented

perspective.

6. Motivation

Learners are intrinsically

motivated and may seek

learning to satisfy such needs

as job satisfaction, self esteem,

quality of life, etc.

Learners are extrinsically

motivated by evaluation,

certification or approval.

Culture

Level 1 – Artifacts

Visible, observable, but can’t see why

Level 2 – Espoused values

What people say they value, goals, philosophy

Level 3 – Underlying Assumptions

Invisible, norms & beliefs established by shared

experience. Those leading to success are reinforced; those leading to failure fade away.

Mostly unconscious, so members may not be aware of them.

Six-P Evaluation Framework (Marker)

Perception. The first short-term element, perception, is the same as Kirkpatrick’s level 1,

reaction; it is simply based on indicators of an individual’s emotional or intutive perception of

the intervention. Data collected at this level are often gathered through questionnaires,

surveys, and interviews. As Kirkpatrick points out, while identifying performer perceptions is a

quick and easy measure of an intervention, it is not particularly helpful in assessing that

intervention’s effectiveness or efficiency.

Indicators might include performer perception of:

• The effectiveness of the intervention.

• How well the intervention was implemented.

• The benefit of the intervention to the performer.

• The benefit of the intervention to the organization.

• Ideas for improving the intervention.

• The relative advantage of the intervention over alternatives.

• The compatibility of the intervention.

• The simplicity of the intervention.

Potential. The second short-term element, potential, is similar to Kirkpatrick’s level 2,

learning. However, while Kirkpatrick’s learning looks at the impact of primarily instructional

interventions, potential looks at the impact of both instructional and non-instructional

interventions. One’s potential to perform could be increased through training, but it could just

as easily be increased through such a non-instructional intervention as changing the work

environment or enhancing feedback. Potential is the extent to which the user’s potential to

perform has increased beyond what he or she was able to do prior to the intervention, and it

is independent of the actual use of that potential on the job.

Indicators of performer potential might include demonstrations related to:

• An understanding of the intervention.

• Skill in being able to use the intervention in a limited context.

• Use of the intervention’s subparts or supporting tools in a limited context.

• Ability to perform at a higher level after receiving the intervention.

Two assumptions are required for the performance potential to be improved by an

intervention. The first is that the root causes, usually multiple, were correctly identified. The

second is that the solution is effective. Instructional interventions may be slightly more subject

to the influence of these assumptions than non-instructional interventions but the

assumptions appear to apply to both intervention types.

Practice. Six-P’s third and final short-term element is practice. This element mirrors

Kirkpatrick’s level 3, behavior. Like behavior, practice looks at the extent to which performers

choose to apply their new knowledge, skills, tools, or other interventions in the intended

manner to achieve a desired result.

Indicators of practice might include the following:

• Observations of performers using the intervention on the job.

• Residual evidence of the intervention’s use on the job.

• Supervisor or peer accounts of the intervention’s use.

Profit. In its simplest form, profit is best described as the positive or negative economic

impact of an intervention including, but not limited to, ROI. Profit is a long-term indicator since

the economic gain or loss from an intervention can take weeks, months, or even years to

show up.

Some would argue that there is no need to look beyond financial indicators of success,

especially in the world of for-profit business. After all, acting with a concern solely for profit

can save organizations money in the short term and boost quarterly reports. However, such

approaches often ultimately lead to a huge waste of resources and may come at the expense

of long-term financial gains. Yet although a singular focus on profit can be harmful, ignoring

profitability entirely can quickly lead to organizational failure. Even nonprofit institutions must

pay attention to the flow of their financial resources. So as PI practitioners, we must pay

attention to both short- and long-term financial impacts.

It is worth noting that only a small set of businesses (e.g., wholesale distributors) can

successfully focus on optimizing profit. While other types of businesses recognize that

extracting short-term profit may come at the expense of long-term business health, they

typically do not have the tools to balance these considerations. Again, Ed Schneider

(personal communication, April 14, 2009) suggests, “What these businesses lack is the

means for systematically balancing short-term and long-term interests, which is why they

need a framework such as the 6Ps.”

Planet. As greater environmental restrictions are put into place limiting externalized

environmental and societal costs, there will be opportunities for profit for companies that are

already addressing these types of impacts. We argue for long-term stockholder and

stakeholder gain versus short-term stockholder gain at the expense of other stakeholders.

Planet indicators of environmental impact might include:

• Land use—forest or wildlife habitat created, preserved, or destroyed

• Waterborne waste generated or avoided

• Wastewater generated or avoided

• Solid waste generated or avoided

• Greenhouse gas emissions generated or prevented

• Energy consumed or saved

• Toxins leached into the biosphere or maintained safely

• Percentage of packaging materials reclaimed or recycled

People. Society’s perception of value often comes down to the decision to purchase goods

and services (to the extent that consumers in the community have a feasible choice for

alternative products and services). This gives us one reason to think that there are long-term

profit opportunities that businesses may realize by looking at where they come into contact

with the community.

Societal indicators of value might include:

• Wage levels

• Quality of life

• Job availability

• Educational opportunities

• Injuries, occupational diseases, absenteeism, and work-related fatalities

• Community involvement