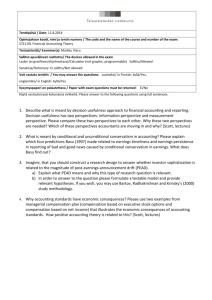

Accounting conservatism and the limits to earnings management

advertisement