Multiple Property Documentation Form

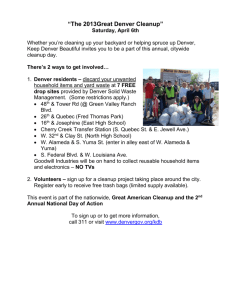

advertisement