ANZ - FSI terms of reference

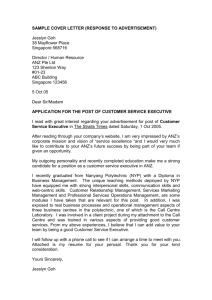

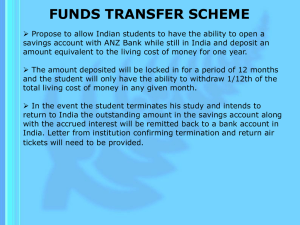

advertisement