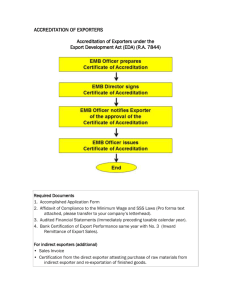

Access to Export Finance in Egypt, April 2004

advertisement