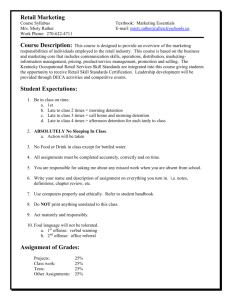

Retail Trade Policy and the Philippine Economy

advertisement