EMAP2012_EarIyMed_In.. - EMAP - Early Medieval Archaeology

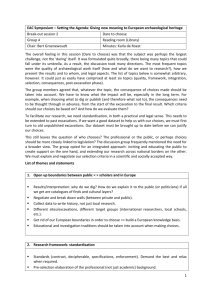

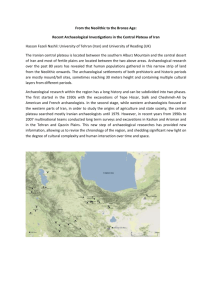

advertisement