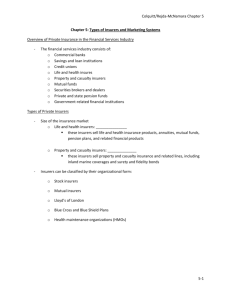

An Overview of the Insurance Industry and Its Regulation

advertisement