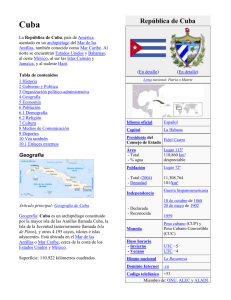

Politics and Civil Society

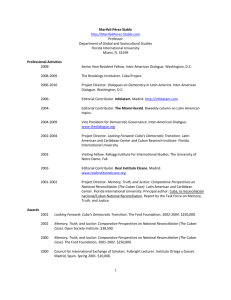

advertisement