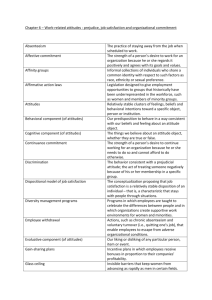

Job Satisfaction and Job Affect

advertisement