A Descent Into Egypt

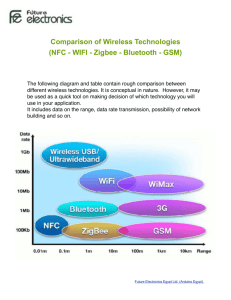

advertisement