Knowledge Bases and Ontologies

advertisement

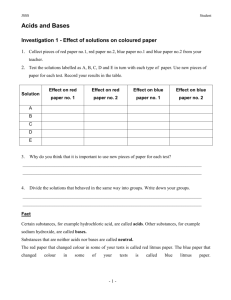

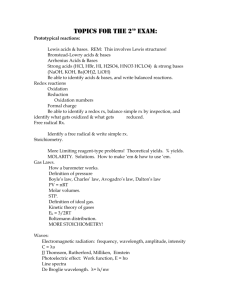

. K N O W L E D G E M A N A G E M E N T Using AI in Knowledge Management: Knowledge Bases and Ontologies Daniel E. O’Leary, University of Southern California C ONSULTING AND PROFESSIONAL services firms are often among the first organizations to adopt a new technology. The reason is clear: they’ve got to know the technology before their clients do.1 Consequently, there appears to be a technology life cycle in consulting firms, where the firms first try the technology for internal use, before selling that same technology to their clients in the form of consulting engagements. We see this process at work with knowledge-management systems and their two main components: knowledge bases and ontologies. Knowledge-management systems employ a wide range of knowledge bases, especially including best-practices knowledge bases. To use those knowledge bases effectively, the consulting firms must be able to generate ontologies that allow users to pinpoint what resources they need and want. Ontologies and knowledge bases are closely related in knowledge management. Ontologies define the knowledge base’s characteristics and views, while also employing models that are helpful in knowledge-base definition and access. This article looks at the way knowledge bases interact to form effective knowledgemanagement systems, and in particular at the way leading consulting firms such as Price Waterhouse, Ernst & Young, and Arthur Andersen apply those systems to their businesses (see the “Consulting firms” sidebar). 34 THIS ARTICLE LOOKS AT THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE IN KNOWLEDGE-MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS, FOCUSING ON SUCH AI-RELATED TECHNOLOGIES AS KNOWLEDGE BASES AND ONTOLOGIES. BECAUSE THESE TECHNOLOGIES BOTH DEPEND ON PARTICULAR SETTINGS, THE AUTHOR DISCUSSES KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT AS PRACTICED AT THREE MAJOR PROFESSIONAL SERVICES FIRMS. What is knowledge management? Knowledge management is the formal management of knowledge for facilitating creation, access, and reuse of knowledge, typically using advanced technology. Knowledge-management systems contain numerous knowledge bases, made up of numeric and qualitative data (searchable Web pages, for example). In addition, knowledgemanagement systems often allow discussion groups that focus on a single set of issues or a specific activity, such as particular software or a single consulting engagement. There are many similarities between AI and knowledge management. For example, knowledge-management systems employ 1094-7167/98/$10.00 © 1998 IEEE knowledge bases, but for both human and machine consumption. As elsewhere in AI, a knowledge-management system also depends on ontologies to facilitate communication between its multiple users and links between multiple knowledge bases. In turn, knowledge bases rely on ontologies for unambiguous specification of views and structure. What do knowledge bases do? Knowledge bases contain the content of the knowledge-management system. Knowledge bases in consulting firms. Knowledge bases usually depend on the specific business and domain in which the orgaIEEE INTELLIGENT SYSTEMS . Consulting firms nization is engaged. Consulting firms typically have knowledge bases that include proposals, engagements, best practices, and a wide range of other topics as a part of their knowledge-management systems. Engagement knowledge bases summarize information about different jobs that are captured in working papers, either actual or virtual. Proposal knowledge bases capture information about proposals that the particular firm has made to generate engagements. News knowledge bases provide news releases of interest to the consulting firms, while other knowledge bases allow access to recent journal and magazine articles. Best-practices (or leading practices) knowledge bases provide access to enterprise processes that appear to define the best ways of doing things. Expert knowledge bases identify who in the firm is expert in a particular set of activities. Knowledge-base development. Not only do knowledge bases differ in their content, but also in their development complexity—or the difficulty of developing the knowledge base, relative to other knowledge bases. A number of factors influence this difficulty. First, some knowledge bases capture information that was generated using a limiting technology, such as paper. Consultants have often kept paper-based knowledge bases, including engagement or proposal databases, where the paper format limited access. However, despite these limitations, those consultants did manage to capture the knowledge, so many of the difficulties of capturing the knowledge have already been addressed. Accordingly, knowledge about previously captured information is likely to be better understood than knowledge that has never been captured. Therefore, the fact that a knowledge base has or has not been developed previously—independent of storage format—helps knowledge managers gauge the difficulty of developing that particular knowledge base. Also, many knowledge bases use a single source of information—engagements or proposals, for example. Because these knowledge bases are limited to a single type of information, each type of knowledge base generally is easier to develop and maintain than knowledge bases with new knowledge and multiple sources of knowledge. That’s because there is no need to integrate multiple databases or search for information in multiple locations. Knowledge bases developed from a single source were among the first MAY/JUNE 1998 used. For example, at the consulting firm of Arthur Anderson: “Since the early 1960s, there was a resource known as the Subject Files ... which allowed someone who was a recognized expert in a subject...who wrote a ‘white paper,’ and this was filed and indexed into ‘Subject Files.’”2 Furthermore, knowledge bases can use information from both internal or external sources, although the quality and quantity of external information generally is less predictable and less controllable than internal information. Also, multiple-source knowledge bases derive from decisions based on both acquisition and integration. Consequently, those knowledge bases that require both types of information are more difficult to generate and maintain easy access to than those that gather information from a single source. Finally, some databases use virtually all the information available on a source document, such as accounting documents and, in particular, purchase orders. However, in such other databases as best-practices databases, the information must be abstracted, synthesized, or integrated with other information. Development complexity of the knowledge base generally increases as the data is manipulated. Best-practices knowledge bases. These knowledge bases are particularly complex and difficult to develop. As noted by Arthur Andersen: We underestimated the sheer effort necessary to translate ... knowledge about best practice into useful explicit knowledge. The central team could not, on its own, extract the ... knowledge of the consultants and the professionals in the field.... After a significant effort, the team had produced a CD-ROM with the classification scheme, but only 10 of the 170 processes populated, and with limited information. Further, the information was not actionable—it added little to those with deep knowledge of the area, and Content identification Arthur Andersen is headquartered in Chicago and Geneva, Switzerland, with 370 offices in 90 countries. They have approximately 45,000 employees worldwide. Revenues are more than $5 billion. They focus on accounting, auditing, and tax services; business consulting; and economic and financial consulting. Ernst & Young is headquartered in Cleveland and New York and has roughly 75,000 employees worldwide. They focus on assurance and advisory business services, management consulting, and tax services. Price Waterhouse is headquatered in New York and has over 100 offices in 118 countries. They offer accounting, auditing, tax, and consulting services to companies and government agencies. They have KnowledgeView Centers in Dallas and London. was not enough to help those who had less experience....The initial offering almost died an early death—it seemed much effort for little payoff.3 To understand the reasons for complexity and difficulty of developing best-practices knowledge bases, let’s look at Ernst & Young’s model of a development environment for their leading-practices knowledge base.4 Figure 1 shows that best-practices databases draw information from multiple sources, both inside and outside the firm. This content must be ranked, abstracted, synthesized, and reviewed. Best-practices knowledge bases fit each of the criteria of difficulty I laid out earlier. Best-practices knowledge bases are a recent development. There is little evidence of summaries of best-practices knowledge bases prior to the systems we’re discussing here. Arthur Andersen claims that it first started its Global Best Practices knowledge base in 1991.2 As Figure 1 shows, enterprises must search out information from many sources to Internal information Document repositories, engagements Abstract and synthesize Populate External information Journals, articles, studies Review Figure 1. Ernst & Young’s leading-practices knowledge-base development environment. 35 . generate a best-practices database and, because there are no generally available sources of best-practices information, they must search them out as well. Because best practices are constantly changing, enterprises also must constantly change their knowledge bases. They must therefore take a more active approach to developing best-practices knowledge bases than many other types of knowledge bases. As a result, for consulting firms, the existence of best-practices knowledge bases signals the extent of development of a knowledge-management system: less developed knowledge-management systems generally do not have best-practices databases; more developed systems do. What are best-practices knowledge bases? These databases capture information and knowledge about the best way to do things. They capture knowledge about processes, rather than artifacts. A wide range of enterprises have used best-practices knowledge bases. General Motors-Hughes Electronics captured best-process reengineering practices in a database,5 and major consulting firms such as the three we are discussing in this article have also have developed bestpractices knowledge bases. Arthur Andersen’s KnowledgeSpace. Figure 2 shows Arthur Andersen’s Global Best Practices knowledge base. Within GBP, Arthur Andersen defined the types of knowledge to be included in the knowledge base: best practices by process, process definitions, examples of companies applying the process, relevant engagements by process, internal experts, performance measures, presentations, and studies and articles. Recently, KnowledgeSpace (http://www. knowledgespace.com) became available as a service over the Internet to subscribers. In addition to having access to best-practices information, subscribers now can access news, discussion groups, and other resources. Subscribers currently can access a small percentage of the best-practices knowledge base and the basic framework. Materials include a definition of the process, an executive summary, and a questionnaire that users can fill out to provide information regarding the particular processes at their firms. Questions take a yes-no format—for example, “Managers of purchasing departments accept 36 accountability for its performance?”—suggesting that a best practice relates to acceptance of accountability. Ernst & Young’s Leading Practices KBase. For its own internal use, Ernst & Young has developed a knowledge base of over 5,000 leading practices, which it has deployed in over 30 countries. The knowledge base contains information from five sources: benchmarks (quantitative values of performance measure by industry or company), war stories (experience of a specific company that implemented a leading practice), enablers (detailed analysis of tools that aid the lead practices), lead-practice descriptions; and reference materials (leading practices source materials). This firm has broken its leading practices knowledge base into eight categories with the following approximate number of entries • • • • • • • • executive processes (1,163) finance (1,488) new business development (430) knowledge management (222) order management (702) production and service delivery (421) supply chain management (1,172) support and shared service (945) In addition, we can view their knowledge base of leading practices from an industry perspective (also with the number of entries): • automotive (139) • energy (715) • financial services (622) Understand markets & customers Develop vision & strategy • • • • • • • health care (62) insurance (96) life science (50) manufacturing (860) retail (406) service (47) transportation (32) Price Waterhouse’s Knowledge View. Price Waterhouse was one of the first consulting firms to develop a best-practices knowledge base through its KnowledgeView system (see Figure 3), which it generated solely for internal use and does not make directly available to subscribers. KnowledgeView organizes processes into two basic categories: value chain (productive) and support (overhead) processes. Reportedly, the system recently had over 4,000 entries. Price Waterhouse has translated its ontology for KnowledgeView into five languages and uses it on five continents. KnowledgeView’s knowledge base has four views. The process view arranges the knowledge base by different overall processes, such as customer service or design and engineering. The industry view organizes processes by different industries, such as aerospace or chemical. The performance measure view focuses on performance results in terms of quality, cost, and time measures. Finally, the best-practices database also has an enabler view that captures information about how the best practices are used in terms of technology, people, other processes, and organization structure. Comparing best-practices models. The models of the best-practices knowledge Design products & services Market & sell Produce & deliver for manufacturing organization Produce & deliver for service organization Invoice & service customers Develop and manage human resources Manage information Manage financial and physical resources Execute environmental management program Manage external relationships Manage improvement and change Figure 2. Arthur Andersen’s Global Best Practices knowledge base. IEEE INTELLIGENT SYSTEMS . bases for these three consulting firms are similar. The value-chain process models (Figures 2 and 3) from Arthur Andersen and Price Waterhouse appear similar, with both focusing on models that contain basic processes of marketing and sales, products and services, production, and distribution and customer service. Both models also include similar views of the support functions, with concern for human resources, financial resources, external relationships, environmental issues, information and systems, and business improvement. In addition, the knowledge sources for each of the best-practices knowledge bases are also similar. Each provides best practices by process, performance-measures benchmarks, industry-based processes information, and reference materials such as studies and articles. Also, at least two—Ernst & Young and Price Waterhouse—provide information about technology enablers, and those same two are available only for internal users, while KnowledgeSpace’s Global Best Practices is available both internally and externally to subscribers. While there are some apparent differences, these might result simply from differences in disclosures about the best-practices databases. Ernst & Young indicates that it captures “war story” information. Arthur Andersen captures examples of companies applying the practice, engagements by process, and experts in each area. In recognizing the high cost of developing and maintaining these models and knowledge Perform marketing and sales Define products and services bases, at least one consulting firm thought it would be possible and desirable for firms to form coalitions that could share development costs. Other firms, however, apparently see model and knowledge-base development as providing a competitive advantage and so do not want to share development. How do KM ontologies work? Ontologies are explicit specifications of conceptualizations.7 These knowledge-based specifications typically describe a taxonomy of the tasks that define the knowledge. Within the context of knowledge-management systems, ontologies are specifications of discourse in the form of a shared vocabulary. They can differ by developer and industry. Each consulting firm we have been examining has built or is building its own ontologies. Because these enterprise ontologies are so costly to develop and maintain and are constantly changing, ontology or taxonomy issues are emerging as some of the most important problems in knowledge management.8 Need. A number of factors drive the need for ontologies in knowledge management. First, because knowledge-management systems employ discussion groups, if users are going to find discussion groups for either raising or responding to an issue, they must be able to isolate which groups are of interest. Ontologies serve to define the scope of these group discussions, with ontology-formulated top- Produce products and services Manage logistics and distribution Manage financials Manage corporate services and facilities Manage external relationships Manage environmental concerns Perform business improvement Manage human resources Provide legal services Perform planning and management Perform procurement Develop & maintain systems and technology Figure 3. Price Waterhouse’s KnowledgeView multi-industry process technology. MAY/JUNE 1998 Perform customer service ics used to distinguish between what different groups discuss. Without an ontology to guide what the groups discuss, there can be overlapping topics discussed in different groups, making it difficult for users to find a discussion that meets their needs. In another scenario, multiple groups might address the same needs, but possibly none would have all the required resources to address a particular user’s needs. Also, knowledge-management systems must provide search capabilities. On the Internet, searches will often yield thousands of possible solutions for search requests. This might work in Internet environments, but it generally is not appropriate in individual organizational Intranet environments. To provide an appropriate level of precision, knowledge-management systems need to unambiguously determine what topics reside in particular knowledge bases: “For the user, the right [ontology] means the difference between spending hours looking for information or going right to the source.”6 Furthermore, knowledge-management systems often provide filtering capabilities. Filtering systems (such as GrapeVine, http:// www.gvt.com) let one filtering source examine substantial amounts of information and (hopefully) direct the information of interest to the appropriate source. Those filters can be either computer-based (such as intelligent agents) or human-based. To use a filtering system, users typically must specify keywords or concepts (depending on the nature of the filtering system) that capture the nature of the desired knowledge. An ontology therefore is essential to capture the set of filter needs. Ontologies facilitate reusability of artifacts archived in the knowledge-management system as well. For example, consulting firms typically archive an artifact referred to as a proposal, which contains information about proposals made to do revenue-generating work for other firms. Proposal knowledge bases can be quite large, so it is critical that users be able to find what they are seeking. To determine whether a previous proposal is similar enough for potential reuse, proposal users must have them categorized across the common dimensions of an ontology, such as domain or industry. For easier archiving, ontologies need to categorize virtually all artifacts in consultant knowledge bases. Finally, knowledge-management systems provide opportunities for collaboration and use of expertise. However, without an appro37 . priate set of ontologies, the lack of a common language might cause confusion in collaboration. Confusion could also arise in the choice of collaboration partners. A knowledge-management system tries to facilitate contact between experts and people in search of their expertise. If a clear ontology of expertise is not available to support such contact, those expertise seekers will not find the experts they are seeking or will find experts whose services they do not need. Desirable characteristics. When is one ontology seen as preferable to another ontology? What characteristics drive preferability? Knowledge managers have a number of variables that facilitate choice. • Cost-beneficial. For-profit businesses such as consulting firms necessarily must operate on cost-beneficial decisions. Because the generation of an ontology must be cost-beneficial, firms might feel pressure to collaborate or use existing ontologies or derivatives of existing ontologies. • Decomposable. For discussion groups and knowledge bases to have a well-defined audience, the ontologies on which they are based need to be decomposable into relatively independent chunks of knowledge, with little overlap. To provide for searchable knowledge, ontology chunks must also be independent; otherwise, definitions of terms will overlap and searches will be ineffective. • Easily understandable. Clearly, an ontology’s intended users must be able to understand and use it. Ensuring that materials are well-defined and graphically illustrated will increase understandability. Generally, the easier something is to understand, the less education will be required for its use and the fewer mistakes its users will make. • Extensible. Knowledge changes, sometimes very rapidly, so ontologies must be extensible to new concepts. Ontologies developed for federations must also let organizations add their own unique aspects to an ontology, so they must accommodate different organizational settings and requirements. • Maintainable. Knowledge is mobile, so knowledge bases and ontologies need to change over time. To facilitate that change, knowledge must be packaged in a format that is easily maintainable—as a database, for example. 38 • Modular and interfaceable. Ultimately, ontologies must interface with other ontologies. Knowledge-management systems typically have multiple knowledge bases and discussion groups, each potentially having its own ontology. There must be a way to bring the multiple, potentially conflicting ontologies together for search and other capabilities. • Theory/framework-based. If an ontology is based on a theory, that framework can facilitate many of the choices that need to be made. A framework can mitigate issues of redundancy and conflict. The frameworks in Figures 2 and 3 both can facilitate categorization of best-practices knowledge. • Tied to the information being analyzed. While ontologies can exist within an ONTOLOGIES PROVIDE THE STRUCTURE TO FACILITATE DRILLING DOWN IN THE FRAMEWORKS TO PROVIDE INCREASING LEVELS OF DETAIL IN THE BEST-PRACTICES KNOWLEDGE BASES. organization, those organizations do not operate independently of the rest of the world. Any ontologies an organization builds therefore must tie back to the rest of the world. For example, if reengineering is a term used by the rest of the world, that term should have a similar understanding within the firm. Otherwise, ambiguity can arise about definitions when integrating external information. This issue is particularly important if the knowledge base is to contain information from external sources, such as articles from journals and magazines. • Universally understood or translatable. While an ontology ideally will be universally understood, in this era of multinational firms, that is at best an ideal. As a result, if an ontology is not universally understood, it should be translatable, including from dialects. Tools. A number of tools have been generated to attempt to facilitate development of knowledge bases satisfying the criteria I have just listed. These include database systems, search tools, theory-based models, and visualization approaches. • Databases and knowledge bases. Ontologies provide both a structure for developing knowledge bases and a basis for generating views of knowledge bases stored on a range of mediums, including the Web, Lotus Notes, and general database systems such as Oracle. For example, Price Waterhouse uses a Lotus Notes database to store Knowledge View, which has different views on process, industry, performance measure, and enabler. Most importantly, the environment lets users partially structure the knowledge and facilitates the desirable characteristics summarized above, such as extensibility and maintainability. • Search tools. Increasingly, as knowledge bases grow larger, search is becoming a critical aspect of knowledge-management systems. A number of tools recently developed to facilitate search as a result: Autonomy (http://www.agentware.com), Magic Solutions (http://www.magicsolu tions.com), and Open Text (http://www. opentext.com), among others. Search capabilities increase with an easily understandable ontology that ties to the rest of the world’s existing information, without conflicts. • Theory/framework-based models. Developing an ontology requires the generation of a dictionary that captures agreed-on term meanings. That dictionary typically is available as a knowledge base in the knowledge-management system. Consulting firms base their ontologies on frameworks, such as the models in Figures 2 and 3, that help them elicit dictionary items. • Visualization tools. Visualization can be one of the primary tools for managing and using an ontology. Visualization lets users view data from multiple perspectives so that they can identify data relationships in data that will help them find what they are seeking. A visual version of the ontology would allow a user to visually follow a concept to its nearest neighbors or analyze the overall space for interesting related or unrelated concepts. A theory-based framework, such as Figures 2 and 3, facilitates visualization of ontologies. In addition, knowlIEEE INTELLIGENT SYSTEMS . Coming this year in IEEE Internet Computing July ❖ August Internet Search Technologies Guest Editors Robert Filman, Lockheed Martin, and Sangam Pant, Lycos September ❖ October Software Engineering over the Internet Guest Editors Frank Maurer, University of Calgary, and Gail Kaiser, Columbia University November ❖ IC Online http://computer.org/ internet/ IEEE Internet Computing’s companion webzine; technology roadmaps to the Internet for engineers and computer scientists. IC Online Exclusives... ❖ Interviews: conversations with December the leaders in the field. ❖ Web resources: URLs, Internet Security in the Age of Mobile Code Guest Editors Gary McGraw, Reliable Software Technologies, and Edward Felten, Princeton University event listings, forums. ❖ Industry reports: news from the inside. ❖ And more all the time for 1998. ... you’ll only find them here. edge managers at consulting firms have been examining a number of other tools to generate a visualization of an ontology. In particular, knowledge managers are studying how they can integrate tools such as Perspecta (http://www.perspecta. com) and InXight (http://www.inxight. com) into their knowledge-management systems for both users and ontology management. K NOWLEDGE BASES AND ONTOLogies are closely related in knowledgemanagement systems.9 Ontologies provide some structure for development of knowledge bases as well as a basis for generating views of knowledge bases. For example, in Price Waterhouse’s Knowledge View, the knowledge base contains information on process, industry, performance measure, and enabler. That same information also serves to provide four different views of the bestpractices knowledge base. Thus, each of those views are representative of the structure of the underlying knowledge base, and each are part of the best-practices ontology. MAY/JUNE 1998 Also, at the highest level of abstraction, ontologies define particular knowledge bases—such as the best-practices knowledge base. At lower levels, ontologies serve to define models in particular knowledge bases. Consulting firms find these models quite useful: “Our experience taught us that the common organizing framework was very valuable—it provides us with a common and understandable way to navigate through the knowledge.”6 Ontologies provide the structure to facilitate drilling down in the frameworks to provide increasing levels of detail in the best-practices knowledge bases. References 1. J. Foley, “‘Giant’ Brains Are Thinking Ahead—Professional Service Companies Are Often Among the Early Adopters of New Technology,” Information Week, No. 596, Sept. 9, 1996. 2. Arthur Anderson, American Productivity & Quality Center, Houston, 1997. 3. Knowledge, The Global Currency of the 21st Century, Arthur Andersen, Chicago, 1997. 4. Leading Practices Knowledge Base, Ernst & Young, Center for Business Knowledge, Cleveland, 1997. 5. T. Davenport, “Some Principles of Knowledge Management,” http://knowman.bus. utexas.edu/kmprin.htm, 1997. 6. Welcome to Knowledge View, Price Waterhouse, Dallas, 1995. 7. T. Gruber, “A Translational Approach to Portable Ontologies,” Knowledge Acquisition, Vol. 5, No. 2, 1993, pp. 199–220. 8. D. O’Leary, “Impediments in the Use of Explicit Ontologies for KBS Development,” Int’l J. Human Computer Studies, Vol. 46, 1997, pp. 327–337. 9. D. O’Leary and P. Watkins, “Integration of Intelligent and Conventional Systems,” Int’l J. Intelligent Systems in Accounting, Finance, and Management, Vol. 1, No. 2, 1992, pp. 135–145. Daniel E. O’Leary is a professor at the School of Business of the University of Southern California. He received his BS from Bowling Green State University, his masters from the University of Michigan, and his PhD from Case Western Reserve University. He is the Editor-in-Chief of IEEE Intelligent Systems and is a member of the AAAI, ACM, and IEEE. Contact him at the Univ. of Southern California, 3660 Trousdale Parkway, Los Angeles, CA 90089-1421; oleary@rcf.usc.edu. 39