Managerial Behavior Associated with Managerial Derailment

advertisement

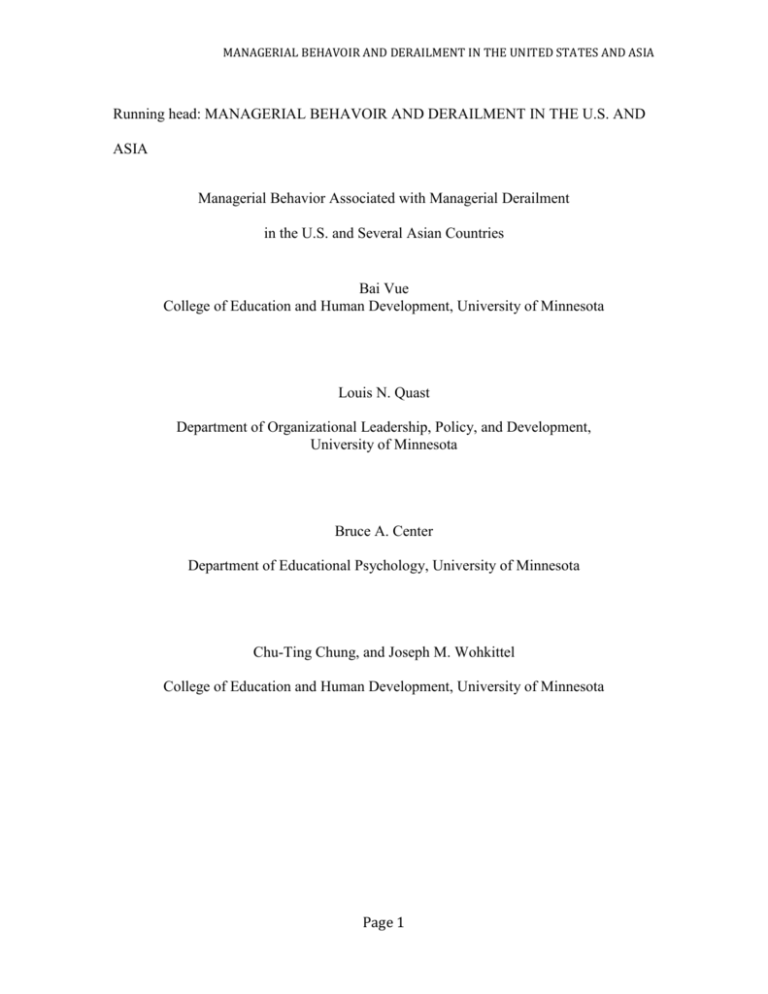

MANAGERIAL BEHAVOIR AND DERAILMENT IN THE UNITED STATES AND ASIA Running head: MANAGERIAL BEHAVOIR AND DERAILMENT IN THE U.S. AND ASIA Managerial Behavior Associated with Managerial Derailment in the U.S. and Several Asian Countries Bai Vue College of Education and Human Development, University of Minnesota Louis N. Quast Department of Organizational Leadership, Policy, and Development, University of Minnesota Bruce A. Center Department of Educational Psychology, University of Minnesota Chu-Ting Chung, and Joseph M. Wohkittel College of Education and Human Development, University of Minnesota Page 1 MANAGERIAL BEHAVOIR AND DERAILMENT IN THE UNITED STATES AND ASIA Abstract Business organizations make significant investments in developing managers to lead the organization through change, growth, and other stressful conditions. Under these conditions, some managers fail based on behaviors under their control. This managerial derailment is costly to both the individual and the organization. Organizations attempt to address this through management development initiatives, often including developmental tools such as a multi-rater feedback instrument. This study explores behaviors, as measured using a multi-rater feedback instrument, that are associated with predicted high risk of managerial career derailment in the United States, China, India, Japan, South Korea, and Thailand. The behavioral data sample of 16,626 managers were obtained using The PROFILOR®, a multi-rater feedback questionnaire that collects responses from supervisors, peers, and direct reports of participants in leadership and management development programs. This study found two behaviors highly correlated with predicted risk of career derailment across almost all the countries under consideration, and separate lists of behaviors uniquely correlated with predicted risk of derailment for each of the countries in the study. Page 2 MANAGERIAL BEHAVOIR AND DERAILMENT IN THE UNITED STATES AND ASIA Introduction Managers play a great role in organizational effectiveness, therefore, managers who derail can bring on consequences that affect their welfare, co-worker, and eventually the organization (Bunker et al., 2002). Managers‟ behaviors have a direct relationship with the financial performance and climate of the organization (Koene et al., 2002). The cost of executive derailment can run to millions of dollars (Finkelstein, 2004). Understanding the outcomes, such as derailment, associated with specific managerial behaviors is necessary in achieving organizational objectives quickly and cost-effectively (Shipper & Clark, 1992). Managerial derailment occurs when a high potential manager who was expected to advance in their organization failed to do so (Lombardo & McCauley, 1988). Over the past 20 years, this conceptualization of derailment has become ubiquitous within the Human Resource Development community. However, little research has been put forward comparing the behavioral antecedents of managerial derailment in the United States to those in other geographic locations, specifically Asia. In the age of global business, understanding these differences may lead to interventions designed to mitigate the potential for derailment in at-risk managers. Managers in organizations have an effect that is amplified by the size of the group or unit under a manager‟s direction. Because of this, organizations invest in development, in part to avoid the costs of managerial derailment. Executives who derail can cost over 20 times their salary to their organization and stall the growth of their region by half (Wells, 2005). Poor managerial performance can affect the results of an entire department or division, and impact the careers of those in contact with the derailing Page 3 MANAGERIAL BEHAVOIR AND DERAILMENT IN THE UNITED STATES AND ASIA manager (Finkin, 1991; Gillespie et al., 2001). Therefore, organizations and managers need to become as aware of the characteristics of managerial derailment as they are aware of the characteristic of managerial success (Gentry, et al., 2007). This study was developed in response to the need to identify and understand the specific behaviors displayed by individuals in managerial leadership roles in organizations that are associated with predictions of high risk of managerial derailment, comparing the patterns discovered in the U.S. and several Asian countries. Analysis of behavioral patterns displayed by managers on the job is a common practice of HRD professionals as they provide feedback to managers using multi-rater feedback instruments as part of an organizational leadership development initiative. Managerial behavior Managers are “responsible for managing the capability and competent human energy of an organization to accomplish important tasks” (Lohmann, 1992); therefore, it is necessary to study the behaviors of managers because they do have “specific, quantifiable impact on organizational effectiveness” (Quast & Hazucha, 1992). The reporting and analysis of managerial behavior is considered to be a crucial element of such management development initiatives (Smither, et al., 2005) because of the impact a manager‟s behavior may have on the job performance of employees in an organization. Therefore, the measurements of managerial behavior, and the investigation of the relationship between such behavior and predictions of the high risk of managerial derailment, are the central foci of this study. Multi-rater feedback instruments are used as part of managerial development initiatives in over 25% of U.S. organizations (Antonioni, 1996), and are increasing in Page 4 MANAGERIAL BEHAVOIR AND DERAILMENT IN THE UNITED STATES AND ASIA ubiquity (Brutus and Derayeh, 2002; Rose and Walsh, 2004; Brutus et al., 2006). Using multi-rater feedback instruments to identify specific behaviors gives individuals and organization the information that helps them be successful. Atwater et al. (1995) concluded that overall leaders‟ behaviors showed improvements after receiving multirater feedback. It also helps organizations retain their managers, and avoid the use of additional scarce resources to recruit, train, and develop replacement managers. This study identifies behaviors of managers, as measured on a multi-rater instrument, which are associated with predictions of high risk of career derailment in the United States and several Asian countries. Derailment in the United States and Asia McCall and Lombardo (1983) conducted some of the first derailment research in the United States by interviewing executives about derailing individuals. Those interviews and subsequent research (Morrison et al, 1987; Lombardo & McCauley, 1988; Van Velsor & Leslie, 1995; Leslie & Van Velsor, 1996) led to the identification of five behavioral clusters associated with derailment: problems with interpersonal relationships; difficulty leading a team; difficulty changing or adapting; failure to meet business objectives; and too narrow function orientation. These clusters are, however, generalizations based on limited samples. They are representative of the United States only at earlier point in time and their relevance in 2011 let alone cross-culturally is questionable. Furthermore, the clusters outlined above cannot be broken down into discrete behaviors, which limits their utility in applied practice. A better understanding of the behaviors in them is necessary so that HRD practitioners can learn to detect them before derailment occurs. Page 5 MANAGERIAL BEHAVOIR AND DERAILMENT IN THE UNITED STATES AND ASIA Career derailment research outside the United States is somewhat sparse. In fact, previous comparison of the behaviors associated with derailment in the U. S. and Asian countries could not be found. Research comparing derailment in Europe and the U. S. tells us that agreement among raters regarding a manager‟s level of performance is more closely associated with derailment in the United States than it is in European countries (Atwater et al., 2005). Additional research exploring derailment in Latin America has found that in hierarchal cultures where priority is put on the group over the individual, excessive emphasis is placed on managers‟ people oriented behaviors (Varela & Premeaux, 2008). Although limited in scope, existing research regarding career derailment in Asia may suggest that cultural differences may result in different behavioral patterns being associated with derailment. Cultural differences between geographic regions in Asia have been associated with patterns of self-ratings of managerial performance (Gentry, Yip, & Hannum, 2010). The purpose of this study is to identify behaviors associated with derailment in the United States and Asian Countries. Therefore, the research question being addressed is as follows: What are the managerial behaviors, as described by the manager’s boss, that are associated with predictions by the same boss of a high level of risk of derailment among managers in the United States and five Asian countries? The overriding purpose of the study was to inform ongoing HRD and management development practice in a useful way. Therefore, the study was completed in the “context of discovery” rather than the “context of justification,” a distinction that Page 6 MANAGERIAL BEHAVOIR AND DERAILMENT IN THE UNITED STATES AND ASIA actually originated with Reichenbach (1938), although it is commonly associated with Karl Popper (1959). In the “context of discovery” approach to research, the investigator remains open to purely empirical observations. Analytic methodologies are chosen to take advantage of natural observations and existing data. Accordingly, the methods used were largely exploratory. Method Instrument The behavioral data gathered for this study were taken from The PROFILOR®, a multi-rater feedback questionnaire that collects responses from supervisors, peers, and direct reports of participants in leadership and management development programs. It is based on several decades of consulting experience and research on management and leadership. It was developed from a review of the management and psychology literatures, exhaustive analysis of a large Management Skills Profile data base (Sevy, Olson, McGuire, Frazier, & Paajanen, 1985), job analysis questionnaires, and interviews of hundreds of managers representing many functional areas and most major industries. The PROFILOR® (Hezlett et al, 1997) contains 135 items, grouped by the publisher into 24 competency scales, and further grouped, on the basis of factor-analysis, into 4 meta-factors: People Leadership, Personal Leadership, Thought Leadership, and Results Leadership. These 4 meta-factors are replicable, broad performance factors based on factor analysis of over 50,000 cases. The PROFILOR® is intended to represent behavioral performance competencies required of managers generally. Median internal consistency reliabilities for PROFILOR® scales range from 0.75 for the self perspective to 0.90 for the direct report perspective. Interrater reliability Page 7 MANAGERIAL BEHAVOIR AND DERAILMENT IN THE UNITED STATES AND ASIA computed as intraclass correlation coefficients for three raters range from .47 to .60 for peers and from .48 to .61 for direct reports (Personnel Decisions International, 2000). Participants This study used only the responses from supervisors. The data used in this study are part of a larger set of data collected as the assessment component in the normal course of the delivery of leadership development programs designed and conducted by a major organizational psychology consulting firm, Personnel Decisions International. 39,891 individuals, participating in development programs at the request of their employer, provided the archival data for this investigation. In our sample population 66% were men, 34% were women. In Asia, the percentages were even more disproportionate: 86% were men. Managers were informed that completion of each instrument was voluntary, that they would receive personal feedback as part of the program, and that their data would be available in aggregate form for research purposes, although no individual results would be revealed in any way. Each participant signed a release form indicating their consent to these uses of the data collected in the program. Procedure The purpose of this study was to create a parsimonious set of PROFILOR® behaviors among the U.S. and six Asian countries that are associated with the supervisor‟s prediction of the likelihood of their employee‟s career derailment. Managers who were expatriates in the country they were working were eliminated. This was due to confounding of cultural and behavioral expectations among ex-pat managers. There are three sources of variation that might account for the behavior of these managers: Page 8 MANAGERIAL BEHAVOIR AND DERAILMENT IN THE UNITED STATES AND ASIA Influence of culture in which the manager is working; the influence of the culture the manager is from; and the unique impact of the clash of these two cultures. At present, there is no effective way to parse out these sources of variation, so we have eliminated ex-pat managers from the study. This enabled us to identify the impact of the culture of the country in which managers in this study are working. Supervisor‟s prediction of the risk of career derailment was scored on a 5 point Likert-style scale: 1=not at all, 2=to a little extent, 3=to some extent, 4=to a great extent, 5=to a very great extent Not surprisingly, ratings were highly skewed, with only 6.0% choosing 4 or 5, while 67.7% chose 1 or 2. Scores of 3 (moderate risk), were eliminated, the remaining scores dichotomized into (1,2): Unlikely to derail and (4,5): Likely to derail. Logistic regressions were used to select the behaviors in the model. Since all of the PROFILOR® behaviors are highly correlated (average r = .43), methods such as backward selection or best-subset regression would be inappropriate. Both of these techniques, for slightly disparate reasons, would result in the inclusion of many behaviors with spurious beta coefficients: e.g. a behavior that negatively predicts derailment, would be selected with a significant positive coefficient, when in the company of similar behaviors. Therefore a simple stepwise procedure was used; spurious predictors were eliminated, and the procedure terminated when the improvement to Nagelkerke Pseudo R2 became trivial (<.001 for the full sample). It should be noted that individually, nearly all of these behaviors are statistically significant predictors of derailment. A very large sample size and an even larger halo effect among their rating supervisors assure this. Page 9 MANAGERIAL BEHAVOIR AND DERAILMENT IN THE UNITED STATES AND ASIA A second concern was the number of behaviors to choose from. While the full sample, even after eliminating non-expats and mid-level derailment predictions, contained 16,626 managers, the U.S. alone contained 14,236 of them. The six Asian countries had from 80 (Thailand) to 1495 (Japan), clearly far fewer subjects than one could trust in a stepwise logistic regression with 135 independent variables. This model was chosen using a three-step process. First a stepwise logistic regression was applied separately to the U.S. and the six Asian countries combined, choosing the „best‟ non-spurious predictors for the U.S. and for Asia. Second, stepwise logistic regression, however unstable, was run on the six Asian countries individually. Again, the best predictors were kept, that did not overlap with the first group. Finally, stepwise regressions were run in blocks, allowing first, the selection from the overall model (U.S. and Asia), and secondly allowing the selection from any of the behaviors unique to one or more Asian countries. Again, it should be noted that many of these behaviors act as proxies for each other. We were looking for a model both highly predictive and parsimonious. This technique reduced the set of possible independent variables from 135 behaviors to blocks of 11 and 7 behaviors. Results The purpose of this study was to explore the managerial behaviors, as described by the manager‟s boss, that are associated with predictions by the same boss of a high level of risk of derailment among managers in the United States and several Asian countries. Results revealed that there are a few common behaviors that are associated with high risk of managerial career derailment in the countries examined for this study (see Table 1). Additional investigation led to the identification of unique behaviors Page 10 MANAGERIAL BEHAVOIR AND DERAILMENT IN THE UNITED STATES AND ASIA significantly correlated with predictions of derailment risk in each of the examined countries. The Nagelkerke Pseudo R2 measured in each of the countries suggest that these items are useful indicators. It is important to note that in all cases, it is low scores on the behaviors identified that are correlated with predicted risk of derailment. Discussion This study was developed to inform ongoing HRD and management development practices in mid-to-large size organizations in a useful way. Managers may use this study to aid them in enhancing their effectiveness. HRD professionals may use this study to focus their attention on behaviors that are associated with prediction of high risk of managerial career derailment and help their clients to avoid such career consequences. The purpose of this study was to create a parsimonious set of PROFILOR® behaviors, for managers in the U.S. and five Asian countries, which are associated with the supervisor‟s prediction of the potential of their employee‟s career derailment. Results revealed that there are two common behaviors identified for almost all of the countries examined for this study where low scores are associated with prediction of high risk of managerial career derailment, and several unique behaviors significantly correlated with predictions of derailment risk in each of the examined countries. The large Nagelkerke Pseudo R2* measured in each of the countries suggest that these few items are useful, practical indicators of risk of managerial derailment. It is important to note the two behaviors identified in four or more of the six countries under consideration, in which low scores are correlated with predicted risk of managerial career derailment. First, managers who are unaware of their strengths and Page 11 MANAGERIAL BEHAVOIR AND DERAILMENT IN THE UNITED STATES AND ASIA weaknesses are more likely to derail. Second, managers who cannot maintain an effective relationship with higher management are more likely to derail. Overall, the male managers outnumbered the female managers at a ratio of 2-1 in the sample used for this study. This could have an impact on the behaviors identified in the result. The impact may be more significant for the Asian countries such as Japan, with only 5% female managers. Particularly in all the Asian countries in this study, these behaviors may not be very reflective of the potential for high risk of managerial career derailment for female managers. Further research is needed to more effectively aid HRD professionals when coaching and developing female managers in these Asian countries. When comparing behaviors where low scores are associated with managerial career derailment in the U.S. and Asia, there are unique behaviors that are associated with managerial derailment in the Asian countries that are not associated with derailment in the U.S., and vice versa. This suggests that derailment patterns in the U.S. and Asia are not the same. HRD professionals responsible for coaching and developing managers would do well to be aware of these differential patterns when working with managers in these countries. Limitations of this study were imposed by the use of an existing data base of responses gathered by HRD professionals in a large consulting practice, PDI Ninth House, in the course of delivering leadership and management development programs to managers who were employees of client organizations at the time the programs were delivered. Relevant demographic variables were gathered at the time the instruments were administered. Demographic data suggest that the sample is representative of managers in mid- to large-sized organizations in the private sector in the United States, Page 12 MANAGERIAL BEHAVOIR AND DERAILMENT IN THE UNITED STATES AND ASIA China, Japan, Thailand, South Korea, and India. There is no attempt to generalize these data to describe either managers of entrepreneurial start-ups, managers of small businesses, or the general population in the countries listed, or behaviors associated with derailment in any other countries. The behavioral data gathered for this study were taken from The PROFILOR®, a multi-rater feedback questionnaire that collects responses from supervisors, peers, and direct reports of participants in leadership and management development programs. This represents only one type of performance data, not all possible measures of performance. Page 13 MANAGERIAL BEHAVOIR AND DERAILMENT IN THE UNITED STATES AND ASIA Table 1. Managerial behaviors associated with derailment and pseudo R2 by country. Country United States n=14,236 Pseudo R2 0.476 Behaviors related to managerial career derailment demonstrates awareness of own strengths and weaknesses develops effective working relationships with higher management China n=399 0.537 *creates an environment where people work their best; *expresses disagreement tactfully and sensitively; *develops effective working relationships with peers; *has the confidence and trust of others. demonstrates awareness of own strengths and weaknesses develops effective working relationships with higher management Japan n=1,495 0.380 *knows which battles are worth fighting; *treats people with respect; *provides clear direction and defines priorities for the team *fosters the development of a common vision. develops effective working relationships with higher management *has the confidence and trust of others; *accurately identifies strengths and development needs in *lives up to commitments. demonstrates awareness of own strengths and weaknesses *shows consistency between words and actions. demonstrates awareness of own strengths and weaknesses others; South Korea n=131 0.289 India n=285 0.186 Page 14 MANAGERIAL BEHAVOIR AND DERAILMENT IN THE UNITED STATES AND ASIA develops effective working relationships with higher management Thailand n=80 0.711 develops effective working relationships with higher management *speaks effectively in front of a group * denotes behaviors unique to individual country Page 15 MANAGERIAL BEHAVOIR AND DERAILMENT IN THE UNITED STATES AND ASIA References Antonioni, D. (1996). Designing an effective 360-degree appraisal feedback process. Organizational Dynamics, 25, 24-38. Atwater, L. E., Roush, P., & Fischthal, A. (1995). The influence of upward feedback on self and follower ratings of leadership. Personnel Psychology, 48, 35 – 59. Atwater, L. E., Waldman, D.W., Orstroff, C., Robie, C., & Johnson, K. (2005). Self-other agreement: Comparing its relationship with performance in the U.S. and Europe. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 13, 25-40. Baron, A. (1999). Communicating at the speed of change: Make change a success by enabling people to understand it. Strategic Communication Management, 3, 12-17. Brutus, S., & Derayeh, M. (2002). Multisource assessment programs in organizations: An Insider‟s perspective. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 13, 187-202. Brutus, S., Derayeh, M., Fletcher, C., Bailey, C., Velazquez, P., Shi, K., Simon, C., & Labath, V. (2006). Internationalization of multi-source feedback systems: A sixcountry exploratory analysis of 360-degree feedback. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 17, 1888-1906. Page 16 MANAGERIAL BEHAVOIR AND DERAILMENT IN THE UNITED STATES AND ASIA Bunker, K., Kram, K., & Ting, S. (2002). The young and the clueless. Harvard Business Review, 80, 80-87. Finkelstein, S. (2004). Why smart executives fail: And what you can learn from their mistakes. New York, NY.: Penguin. Finkin, E. (1991). Techniques for making people more productive. Journal of Business Strategy, 12, 53. Gentry, W., Mondore, S., & Cox, B. (2007). A study of managerial derailment characteristics and personality preferences. Journal of Management Development, 26, 857-873. Gentry, W. A., Yip, J., & Hannum, K. M. (2010) Self-observer rating discrepancies of managers in Asia: A study of derailment characteristics and behaviors in Southern Confucian Asia. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 18, 237-250. Gillespie, N.A., Walsh, M., Winefield, A.H., Dua, J. and Stough, C. (2001). Occupational stress in universities: Staff perceptions of the causes, consequences, and moderators of stress, Work & Stress, 15, 53-72. Goleman, D. (2000). Leadership that gets results. Harvard Business Review, 78, 78-90. Page 17 MANAGERIAL BEHAVOIR AND DERAILMENT IN THE UNITED STATES AND ASIA Hezlett, S. H., Ronnkvist, A. M., Holt, K. E., & Hazucha, J F. (1997). The PROFILOR® Technical summary. Minneapolis, MN: Personnel Decisions International. Koene, B. A. S., Vogelaar, A. L. W., & Soeters, J. L. (2002). Leadership effects on organizational climate and financial performance: Local leadership effect in chain organizations. Leadership Quarterly, 13, 193-215. Kolb, D.M. (2005). Will you thrive – or just survive?, Negotiation, January, p. 3-5. Leslie, J.B. and Van Velsor, E. (1996). A look at derailment today: North America and Europe. Greensboro, NC: Center for Creative Leadership. Lieberson, S., & O‟Connor, J. F. (1972). Leadership and organizational performance: A study of large corporations. American Sociological Review, 37, 117–130. Lohmann, D. (1992). The impact of leadership on corporate success: A comparative analysis of the American and Japanese experience. In Clark, Clark, and Campbell, 1992. Impact of Leadership. Greensboro, NC: Center for Creative Leadership. Lombardo, M. M., & McCauley, C. D. (1988). The dynamics of management derailment (Technical Report No. 34). Greensboro, NC: Center for Creative Leadership. McCall, M. & Lombardo, M. (1983). Off the track: Why and how successful executives Page 18 MANAGERIAL BEHAVOIR AND DERAILMENT IN THE UNITED STATES AND ASIA get derailed. Greensboro, NC: Center for Creative Leadership. Morrison, A.M., White, R.P., & Van Velsor, E. (1987). Breaking the glass ceiling: Can women reach the top of America’s largest corporations? Reading, MA: AddisonWesley. Personnel Decisions International (2000). Unpublished research on PROFILOR® factor structure. Minneapolis, MN: Personnel Decisions International Popper, K. (1959). The Logic of Scientific Discovery. New York: Basic Books. Quast, L. N., & Hazucha, J. F. (1992). The relationship between leaders‟ management skills and their groups‟ effectiveness. In Clark, Clark, and Campbell, 1992. Impact of Leadership. Greensboro, NC: Center for Creative Leadership. Reichenbach, H. (1938). Experience and Prediction. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Rose, D.S., & Walsh, A.B. (2004). Current trends in 360-degree feedback: Overall report (Technical Report 8285). 3D Group. Salancik, G., & Pfeffer, J. (1977). Constraints on administrator discretion: The limited influence of mayors on city budgets. Urban Affairs Quarterly, 12, 475– 498. Page 19 MANAGERIAL BEHAVOIR AND DERAILMENT IN THE UNITED STATES AND ASIA Sevy, B. A., Olson, R. D., McGuire, D. P., Frazier, M. E., & Paajanen, G. (1985). Managerial skills profile technical manual. Minneapolis, MN: Personnel Decisions, Inc. Shipper, F. & Wilson, C. L. (1992). The impact of managerial behaviors on group performance, stress, and commitment. In Clark, Clark, and Campbell, 1992. Impact of Leadership. Center for Creative Leadership, Greensboro, NC. Smither, J., London, M., & Reilly, R. (2005). Does performance improve following multi-source feedback? A theoretical model, meta-analysis, and review of empirical findings. Personnel Psychology, 58, 33-66. Thomas, A. B. (1988). Does leadership make a difference to organizational performance? Administrative Science Quarterly, 33, 388 – 400. Van Velsor, E., & Leslie, J.B. (1995). Why executives derail: Perspectives across time and cultures. Academy of Management Executive, 9, 62-72. Varela, O. E. & Premeaux, S. F. (2008). Do cross-cultural values affect multisource feedback dynamics? The case of high power distance and collectivism in two Latin American countries. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 16, 134-142. Page 20 MANAGERIAL BEHAVOIR AND DERAILMENT IN THE UNITED STATES AND ASIA Walker, C.A. (2002). Saving your rookie managers from themselves. Harvard Business Review, 80, pp. 97-102. Watkins, M. (2004). Strategy for the critical first 90 days of leadership. Strategy & Leadership, 32, 15-20. Wells, S.J. (2005). Diving in. HR Magazine, 50, pp. 54-59. Page 21