July 2011 New York State Bar Examination Essay Questions

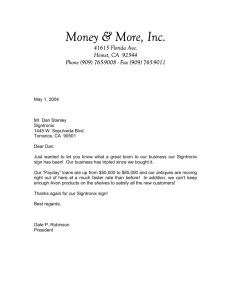

advertisement