02hollythesis

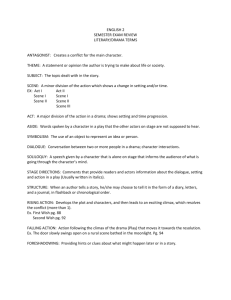

advertisement