Student Collaboration in the Online Classroom

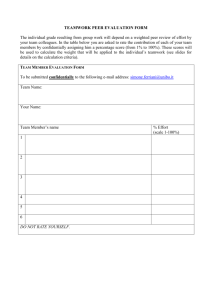

advertisement