Tackling child sexual exploitation

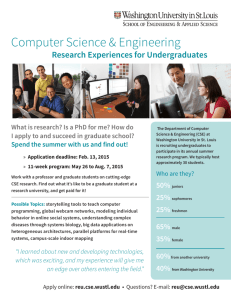

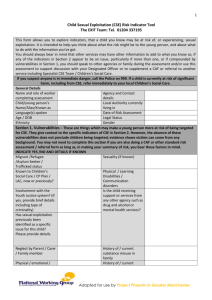

advertisement