Effective approaches to

community awareness raising

of child sexual exploitation:

a review of the literature on

raising awareness of sensitive

social issues

Dr Lisa Bostock

February 2015

Summary

• C

ommunity awareness raising of child sexual exploitation (CSE) is an active and growing

area of policy and practice. Yet, no published evaluations exist of CSE community

awareness activities, making it difficult to assess what works best.

• T

he purpose of community awareness raising depends who is undertaking awareness

raising and the population being targeted. From the perspective of professionals, its

purpose can be grouped into the following categories: prevention, identification and early

intervention and access to advice and support.

• W

hat is less well understood is what children, young people, parents, carers and the

wider community want from CSE awareness raising activities.

• E

vidence from the wider literature on effective methods of awareness raising on sensitive

social issues suggests awareness raising models can be effective but have differential

impact on different groups. Targeted outreach work such as community events, appear

to work well to promote knowledge and understanding with those ‘harder-to-reach’,

including fathers and minority ethnic groups.

• M

odels of awareness raising fall into the following four categories: multi-media

campaigns; outreach via community events; peer educator programmes; and multi-modal

activities that adopt a variety of awareness raising techniques.

• T

he factors that promote effective community awareness raising include: having clear

aims and objectives; understanding the needs of the target audience; engagement with

wider stakeholders; and use of designated workers to promote awareness and access to

services.

• T

his suggests that to have the most effect, it is important to understand the nature and

extent of young peoples’, carers’ and wider community’s awareness of CSE. By doing so,

awareness raising initiatives can be tailored to address any knowledge gaps and activities

developed in line with needs and preferences.

• R

ecent research shows that the majority of parents have at least heard of CSE via media

reporting, but revealed mixed knowledge concerning signs and indicators and risk factors

of vulnerability.

• S

potting the signs of CSE is difficult without disclosure from children and young people.

Children and young people are reluctant to disclose exploitative experiences due to lack

of appropriate responses from services, and normalisation of sexual violence, reflecting

attitudes in wider society.

• N

evertheless, young people identified a desire for more openness about sexual

exploitation and the development of trusting relationships and discussion with peers who

had experience of sexual violence.

• T

here are few examples of CSE awareness raising with the wider community. New but

unevaluated initiatives are working with local faith and community leaders to develop,

appropriate, sensitive CSE awareness raising strategies.

• U

nderstanding effective methods of CSE community awareness raising is in its infancy.

This is a significant gap in the knowledge base and clearly, an area that warrants further

investigation to ensure future effectiveness of such activities.

2

Contents

1 Introduction................................................................................................................... 4

1.1 Families and Communities Against Sexual Exploitation (FCASE).......................... 4

1.2 Research review questions.................................................................................... 4

1.3 Methods................................................................................................................. 5

1.4 Definitions.............................................................................................................. 6

1.5 Purpose of CSE community awareness raising..................................................... 6

1.6 What are the issues?............................................................................................. 7

1.7 Barriers to effective CSE awareness raising.......................................................... 9

2 Different models of awareness raising......................................................................... 10

2.1 Multi-media campaigns.......................................................................................... 10

2.2 Community events................................................................................................. 11

2.3 Peer educator programmes................................................................................... 11

2.4 Multi-model activities............................................................................................. 11

2.5 Effectiveness of awareness raising models.......................................................... 13

3 Factors promoting and hindering the success of models............................................. 16

3.1 Aims and objectives............................................................................................... 16

3.2 Understanding the needs of the target audience.................................................. 16

3.3 Engaging with wider stakeholders......................................................................... 18

3.4 Designated inclusion workers................................................................................ 18

4Young people, parents and wider community views on CSE and

CSE awareness raising................................................................................................. 18

4.1 Parental perspectives awareness on CSE............................................................. 18

4.2 Children and young peoples’ perspectives on CSE............................................... 20

4.3 Wider community views on CSE........................................................................... 22

5 Conclusions and recommendations.............................................................................. 22

Suggested reading........................................................................................................ 24

Useful websites............................................................................................................ 24

References.................................................................................................................... 25

Appendix A: Full search strategy and review methods................................................. 28

3

1 Introduction

It is widely assumed by policy-makers and campaigners that community raising awareness

of child sexual exploitation (CSE) is a ‘good thing’. Yet, awareness raising has been subject

to criticism, with insufficient emphasis placed on its importance by agencies charged with

the responsibilities of safeguarding children[1]. But what is community awareness raising?

How is it conducted and how do we know that it makes a difference? What do children,

young people and their families and carers as well as the wider community want from

CSE awareness raising? If we agree that awareness raising is ‘crucial [to] ‘preventing

sexual exploitation taking place’[2], answering such questions is essential if we are to get

community awareness right for children, young people, their carers and wider community.

This research review reports evidence on effective approaches to community awareness

raising of sensitive social issues. Community awareness raising of CSE is a new

phenomena, hence is an area where practice is ahead of the research and current initiatives

unevaluated. In order to develop the evidence base in this area, the review is part of a wider

evaluation undertaken by the School of Applied Social Studies, University of Bedfordshire of

Barnardo’s Families and Communities Against Sexual Exploitation (FCASE) project.*

*See http://www.beds.ac.uk/intcent/publications for all FCASE reports.

1.1 Families and Communities Against Sexual Exploitation (FCASE)

FCASE aims to:

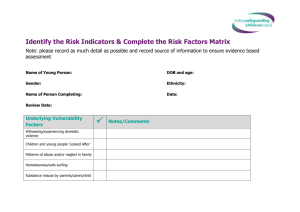

• Develop community understandings of the signs and indicators of CSE.

• Enhance relationships with parents/carers and children and young people.

• Reduce the levels of risk for children and young people.

• E

mpower children and young people make healthier and safer sex and relationship

choices.

• P

rovide support and strategies to enable parents/carers to keep the child or young person

safe.

Additionally, FCASE community events aim to highlight the existence of the project, and

encourage children and young people, parents, carers and local professionals such as youth

workers to make contact with FCASE as necessary.

1.2 Research review questions

In order support development of University of Bedfordshire’s evaluation of FCASE, this

review explores effective approaches to community awareness raising of sensitive social

issues. It aims to identify and describe:

1 different models of community awareness raising;

2 evidence of their effectiveness, with focus on outcomes achieved;

3 factors promoting and hindering the success of these models;

4 the perspectives of children, young people, parents/carers and the wider community.

When identifying and describing the above the review pays particular attention to awareness

raising with Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) groups as well as examples of user-led

initiatives that promote public awareness raising.

4

1.3 Methods

The methods used to identify and organise material in this review were developed by the

Social Care Institute for Excellence (SCIE)[3]. In total, 69 items were identified of which 20

met criteria for inclusion for review. Almost all items report the ‘grey literature’ including

research reports (15); independent and voluntary sector reports (3). Just two items peer

reviewed (see appendix A for full search strategy write up).

Consultation with the project team identified the lack of evaluations of CSE community

awareness raising activities. This meant undertaking searches on topics beyond raising

awareness of CSE within the community to capture learning from the wider literature on

awareness raising on sensitive social issues. In agreement with the commissioners of the

review, topics included:

1 Child protection, including children at risk of online grooming.

2 National evaluation of Sure Start (NESS).

3 H

ealth promotion initiatives including improving take up of chlamydia testing; and

increasing organ donation registry among BME groups.

4 Community-led community safety awareness raising initiatives e.g. gun and knife crime.

These topics are necessarily diverse focused on areas that are directly relevant to CSE

awareness raising e.g. child protection issues but also areas where evaluations have

taken place that affect young people e.g. improving uptake of chlamydia testing or BME

groups e.g. improving organ donation registry. NESS was included because it was known

to have included evaluation of promotional activities, including use of community events.

Raising awareness of gun and knife crime was identified as an area where community-led

initiatives were known to have been developed, particularly by mothers whose families had

been affected. Although, subsequent searches revealed such initiatives have gone largely

unevaluated.

In order to be included for full review, items had to an evaluation study. Studies reporting

the views of children, young people, parents/carers and the wider community were also

included. This reflects the aims of the review to understand their perspectives on CSE and

effective awareness strategies; evidence unlikely to be identified via a focus on evaluation

studies only. Research types included research reports, independent and voluntary sector

reports and peer reviewed papers. Due to time and budget constraints, only UK-based

studies are included for review.

The majority of the items (18) identified are linked. Eight items refer to the National

Evaluation of Sure Start[4-11]; four items are part of the Office of the Children’s Commissioner

(OCC)’s Inquiry into Inquiry into Child Sexual Exploitation in Gangs and Groups (CSEGG)[12-15];

two items refer to the evaluation of the awareness raising campaign to increase chlamydia

testing[16, 17]; and two items are part of the European Commission Safer Internet Plus project

on improving online safety of children and young people[18, 19].

5

1.4 Definitions

In line with Government policy, the review uses the definition of CSE as developed

by the National Working Group for Sexually Exploited Children and Young People

(NWG)1: ‘Sexual exploitation of children and young people under 18 involves

exploitative situations, contexts and relationships where young people (or a third

person or persons) receive ‘something’ (e.g. food, accommodation, drugs, alcohol,

cigarettes, affection, gifts, money) as a result of them performing, and/or another

or others performing on them, sexual activities. Child sexual exploitation can

occur through the use of technology without the child’s immediate recognition; for

example being persuaded to post sexual images on the Internet/mobile phones

without immediate payment or gain. In all cases, those exploiting the child/young

person have power over them by virtue of their age, gender, intellect, physical

strength and/or economic or other resources. Violence, coercion and intimidation are

common, involvement in exploitative relationships being characterised in the main

by the child or young person’s limited availability of choice resulting from their social/

economic and/or emotional vulnerability’[20].

Community awareness raising is more difficult to define, with limited explanations

of what is meant by awareness raising available in the literature. For the purposes

of this review, community awareness raising refers to activities that promote

understanding of CSE with children, young people, their families and carers and

wider community e.g. members of the general public. Activities include: multimedia

campaigns, such as advertising campaigns on television, radio, national and local

press and social media; informal outreach activities such as community-based events

and formalised outreach through home visiting; publicity leaflets and postcards; plays

and performances; films; and targeted work with specific groups such as leaders of

local faith communities. The definition does not include awareness raising among

professionals, such as the police, health and social care staff or youth workers; this

is beyond the scope of this review.

1.5 Purpose of CSE community awareness raising

The purpose of community awareness raising depends who is undertaking

awareness raising and the population being targeted. From the perspective of

professionals, the purpose of awareness raising can be grouped into the following

categories: prevention, identification and early intervention and access to advice

and support. Professionally-led awareness raising activities with young people

are focused on supporting young people stay safe, make positive choices in

relationships and resist unwanted sexual experiences.

For parents, carers and the wider community, awareness raising is focused on

increased understanding of the signs and indicators of CSE. These include: going

missing from home or care; receipt of gifts from unknown sources; involvement in

offending; drug or alcohol misuse; poor mental health, self harm, thoughts or

1

he National Working Group is a support group for individuals and service providers working with children and young people who are at risk of

T

or who experience sexual exploitation. The Group’s membership covers voluntary and statutory services including health, education and social

services.

6

attempts at suicide; and repeat sexually-transmitted infections, pregnancy and

terminations[20]. What is less well understood is what children, young people,

parents, carers and the wider community want from awareness raising activities,

discussed in sections 4-4.3.

1.6 What are the issues?

A series of high profile court cases, research into the impact of gang-associated

sexual violence on women and girls alongside national campaigns such as Puppet on

a String by Barnardo’s have fuelled public awareness of CSE[12, 15, 21-23]. The scale of

the problem is significant with many thousands of children and young confirmed as

victims of CSE or at high risk of sexual exploitation[14]. Child and young people from

a range of ages, ethnicities and sexual orientation as well as some disabled young

people are victims of CSE.

The majority live at home, although a disproportionate number live in residential

care. Girls and young women are more likely to victims but a significant minority are

boys and young men. While the profile of perpetuators is more difficult to identify,

the majority are White males. Men loosely recorded or reported as ‘Asian’ are the

second largest category of perpetrators. There is also overlap with a small minority

of victims who are also reported as perpetuators of abuse[14, 24, 25].

Increased understanding and awareness has meant that CSE has moved up the

policy and practice agenda[2, 13-15, 20, 26-29]. In 2009, the then Department for Children,

Schools and Families issued supplementary guidance to Working Together to

Safeguard Children focused specifically on CSE[20]; with new statutory guidance also

issued by the Welsh Assembly Government[28]. In Scotland and Northern Ireland,

CSE policy and practice is currently subject to enquiry and review[23, 30].

In 2011, the UK government issued an action plan on tackling sexual exploitation[2].

This outlined a series of actions including increasing awareness of CSE among young

people, parents and carers and professionals. In relation to their raising awareness

function, the guidance states that Local Safeguarding Children Boards (LSCBs)

should identify any issues around sexual exploitation, including those arising from

the views and experiences of children and young people in their area. This should

include: awareness raising activities focused on young people; publicity for sources

of help for victims; how and where to report concerns about victims and offenders;

and public awareness campaigns more generally[20].

For children and young people, the guidance emphasises the importance of sex and

relationship education (SRE) to raise awareness about CSE and support children

and young people make safe and healthy choices about relationships. Specialist

education programmes such as Barnardo’s Bwise2 Sexual Exploitation aim to raise

awareness of the rights, risks and responsibilities that equip young people to stay

safe as well as promote young people’s confidence to resist unwanted sexual

experiences[31].

7

In terms of ‘targeted prevention’ for parents and carers, the guidance states that agencies

should consider how best to inform them about patterns of grooming, indicators of risk

of sexual exploitation and the impact of sexual exploitation on children, young people and

families as well as where to access advice and support. Local Authorities (LA’s) should work

specifically with foster carers and staff in children’s homes to raise awareness of CSE[20].

In their review of policy and practice in LSCBs in England, Jago et al’s (2011) found the

impact of the supplementary guidance as ‘limited’, with targeted awareness raising aimed at

young people, their families and carers occurring in less than half of the country[1]. A finding

mirrored by research undertaken in Wales, where a review of local CSE protocols found

awareness of such protocols to be limited to a few key professionals (Clutton and Coles,

2009).

Since publication of the two reviews above, the OCC’s Inquiry into CSEGG has produced

a series of reports[13-15]. A comparison of data collected from LSCBs by the Inquiry and that

gathered by the Jago et al. (2011), indicates that progress has been made with 68 per cent

running awareness-raising programmes[15]. The Inquiry found that 38% of LSCBs have or

plan to run awareness-raising programmes for parents and carers on how

to spot the early

signs of child sexual exploitation; 46% have carried out awareness-raising activity directed

at young people; and 78% have delivered awareness-raising programmes for professionals,

although it is not clear what percentage are foster carers or staff in children’s homes.

The need to achieve greater awareness of CSE to aid prevention and early intervention

not only among professionals, but also the wider public is recognised by the Local

Government Association (LGA). In February 2013, the LGA launched an eight week ‘National

Conversation’ exercise that posed a series of questions on promoting best practice in

awareness raising of CSE[27]. Responses from local LA’s, the voluntary and community sector

and health professionals suggested the following community-led activities:

• t raining community based mentors to deliver workshops in CSE, using an area wide

training scheme and utilising voluntary agencies;

• h

aving CSE stalls with leaflets and trained CSE workers at community events such as

fetes and markets;

• m

aking sure that where CSE is publicised in communities there is follow up with staff that

have a good knowledge and can give well informed advice;

• h

olding safeguarding forums within the community;

• s etting up one-to-one sessions with young people affected and developing peer-topeer support systems;

• inviting professionals to community meetings to speak about CSE and answer any

questions people may have[27].

Responses have informed development of online resource to support councils in raising

awareness of CSE[32]. As part of the resource, the LGA has published case studies from six

LA’s showing how they are tackling awareness raising with partner agencies, young people,

parents, faith groups and local media. All six areas have engaged in schools-based

8

awareness raising activity, including Kent’s work with Barnardo’s to embed awareness of

CSE within its wider safeguarding children’s policy.

Of the other areas, three are actively engaged in wider community-awareness raising:

Rochdale is developing awareness-raising for the Muslim community; Rotherham has

targeted local taxi drivers as well as producing leaflets for children and young people,

parents and carers, and ensuring clear information on the council website; whereas

Blackpool’s ‘Buzz Bus’ travels to communities providing advice, information and support on a

range of health and wellbeing topics, including CSE[33].

1.7 Barriers to effective CSE awareness raising

The LGA also identifies a series of barriers to raising CSE within local communities,

including: stereotypes about the type of person who commits CSE, with some communities

finding it difficult to accept that people within their group could commit CSE; focus

on particular models such as the ‘boyfriend model’ or the ‘gang model’ meaning that

other vulnerable groups, such as young men or victims of peer-on-peer violence can be

overlooked; wider societal perceptions that ‘blame’ the victim for repeatedly returning to

perpetrators; or the view that CSE only happens to children with bad parents leading some

people to mistakenly believe that their child is not at risk. In addition, funding, difficulties

with inter-agency working, offering CSE education to younger children within an already

packed curriculum as well as uncertainty about how to engage with some communities

were all identified as barriers faced by council-led awareness raising activities.

Importantly, lack of evaluation remains a barrier to improving the effectiveness of CSE

awareness raising. Beckett et al. in their review of current responses to CSE for the London

Councils and London Children’s Safeguarding Board, found that while awareness raising was

taking place with parents/carers and children and young people (in around 50% of Boroughs

who responded to this question), very few London Boroughs had undertaken awareness

raising with the wider community. Activities largely focused on written materials, such as

posters and leaflets with some online materials and training courses. However, the impact of

such awareness raising activities was rarely evaluated: just two Boroughs, for example, had

evaluated any aspect of their awareness raising work with children and young people[34].

Becket et al. also found that the education sector was engaged in multi- agency

partnerships, and were a source of CSE referrals, a number of interviewees and survey

respondents highlighted inadequate engagement on the part of schools as a barrier to

awareness-raising with young people. They state that while some schools were positively

engaged in referring children into CSE systems where they have concerns, they were not

always positively engaged with preventative and awareness-raising CSE activities. Only 17

of the 30 survey respondents reporting awareness of any school-based initiatives in relation

to CSE in their area[34]. 9

2 Different models of awareness raising

Given CSE awareness raising is a new area for policy and practice, the current review looked

to the wider literature on effective approaches to awareness raising on sensitive social

issues to derive relevant learning. The review identified four areas where evaluation research

on the impact of awareness raising had taken place: child protection; National evaluation of

Sure Start (NESS); health promotion including: improving take up of chlamydia testing and

increasing organ donation registry among BME groups.

Review of this literature identified four UK-based models of awareness raising. These

models fall into the following categories:

• M

ulti-media campaigns e.g. advertising campaigns on TV, radio, national and local press

and social media

• Community events e.g. outreach via community-based events

• P

eer educator programmes e.g. trainer educators from target populations to improve

awareness of an issue

• M

ulti-model activities e.g. informal outreach such as social events and organised outreach

via home visiting as well as wider publicity materials such as leaflets and merchandise.

2.1 Multi-media campaigns

This model of awareness raising cover a range of advertising activity on TV, radio, national

and local press and use of social media such as Facebook. Two linked studies looked at

the national campaign to increase uptake of chlamydia screening among 15–24 year olds in

England called “Chlamydia: Worth talking about”[16, 17]. The campaign ran between February

and March 2010, on national TV, radio and included online and poster advertising as well as

leaflets, posters and access to logos for local campaigns. The campaign sought to normalise

conversations about the transmission of chlamydia, raise awareness of the risk of untreated

infection and explain the process of diagnosis and treatment among a group at high risk of

infection. The uptake of screening among 15–24 year olds was identified by the campaign

developers as a key indicator to evaluate the campaign[16].

In February 2005, the Scottish Executive introduced a protecting children and young people

pilot campaign in Aberdeen City, Aberdeenshire and Moray[35]. The campaign was non TVbased, consisting of local radio, inserts into local newspapers, outdoor advertising including

posters and bus headliners and posters for the police, GP surgeries and schools. The

campaign was targeted at the Scottish adult population and aimed to: raise public awareness

of child protection issues and the fact that not all children at risk are easy to recognise;

increase public attentiveness to the ‘early signs’ of neglect or harm in children and young

people; emphasise individual and community responsibility in relation to child protection; and

provide a mechanism for people concerned about a child or young person to make contact

with the authorities. The research evaluated both how effective the pilot campaign had been

in terms of communicating its key messages as well as examining wider attitudes across

Scotland toward protecting children and young people.

10

2.2 Community events

Outreach work via community events to raise awareness can be both targeted at particular

population groups or may take place within wider community events. As part of a smallscale study on perceptions and beliefs about organ donation in African, Caribbean and Asian

communities, Clarke-Swaby[36] organised an event to increase awareness of organ donation,

diabetes and kidney disease. The event was held at a local Church Centre and attended by

100 members of the local community. Various health professionals and key public figures

gave presentations on national projects to raise awareness of organ donation and blood

transfusion, high blood pressure and diabetes and their implications for kidney disease;

organ donation and transplantation and barriers impacting the uptake of organ donation.

Donors and recipients also shared personal accounts of giving and receiving a kidney. In

order to measure the success of the event, data on numbers of signed organ donation

registration forms and post event feedback were collected from participants.

2.3 Peer educator programmes

As part of Kidney Research UK’s ABLE (A better life through education and empowerment)

programme, a Peer Educator programme was piloted. The aim of the pilot was to improve

understanding of organ donation among BME communities and to increase the number

of BME organ donors[37]. Peer Educators for the pilot were drawn from BME communities

employed by the local NHS Trust. Peer Educators were given two days training, detailing

the extent of the problem faced by BME groups in relation to both their high risk of requiring

donated organs and the severe shortage of BME donors. Following training, Peer Educators

targeted specific community events such as the East London Mela in Barking Park to

maximise engagement with BME groups. The evaluation had two phases: one looking at the

appropriateness of the model as a way of engaging with BME communities; and phase two

collected feedback from attendees at Peer Educator information stands as well as data on

numbers signing the organ donation register on the day of the event. Interviews were also

conducted with those expressing inclination to sign.

2.4 Multi-model activities

A multi-modal approach to awareness raising was adopted by Sure Start Local Programmes

(SSLPs) to raise awareness of their services to all local households with children under 4

years and increase service uptake[4-11]. Activities included: informal outreach such as social

events; organised outreach via home visiting; press coverage, including advertising and

local radio; distributing Sure Start merchandise such as pens and t-shirts; written materials

in public places; publicity in religious venues; attending local voluntary organisations and

support groups; newsletters; door-to-door leafleting; translating material into different

languages; information sessions for local professionals; surveys and parent/carer

consultations. NESS studied numbers of awareness activities used, extent of reach to

households with children under 4, and use of specific activities with hard-to-reach groups.

Table 3 provides a matrix of the four models identified covering: author, topic area, aims of

awareness raising, method of evaluation and outcomes achieved. 11

Table 1 Matrix of models

Author of

Topic area

evaluation

Awareness raising

activity

Aims of awareness

raising

Evaluation

method

Outcomes

achieved

Scottish Executive[35]

Child protection

Multi-media campaign

Raise awareness of: • child protection issues; • warning signs and indicators; • how to contact authorities with concerns.

Quantitative survey

with general

population

comparison

Increased awareness and

understanding of:

• child protection issues,

particularly among women

with children in the household.

• difficulties of recognising when

child at risk, although only half

agreed with this.

• who to contact, although many

remained confused about who

contact with concerns.

NESS[4-11]

NESS

Multi-model incl:

To identify and raise

Mixed methods: • Informal outreach: awareness of SSLP with

qualitative and

Social events

all families with children

quantitative

• Organised outreach under 4 years within SSLP

via home visiting

locality and promote

• Press coverage

use of services

• Written materials

• Parental/carer consultation • Publicity in religious venues

• Merchandising

Clarke-

Health promotion: Community event plus

BME organ donation TV interview

Swaby[36]

Increase:

Post event feedback. • awareness of need for

BME organ donation

• numbers on organ donation register

• On average, SSLPs used 15+

methods of awareness raising

• In rounds 1 and 2, 54% and 43% respectively of families were

seen at least once by SSLP

• Three quarters of managers

recognise as yet not reaching

whole community

• Of families seen, three quarters

of parents felt SSLP well

advertised but just under ¼ felt

that there was a lack of

information

• Targeted work such dedicated

key workers and targeted social

events worked best with hardto-reach groups e.g. men and

BME communities.

Following the event:

• 30/100 signed the register

In addition:

• Two more people signed

a fter the TV interview

• Five more following attendance

at related-Expo.

Health promotion: Peer educator programme: Increase:

Process evaluation

Increased awareness of BME

Buffin et al.[37]

BME organ donation ABLE

• awareness of need for

with peer evaluators organ donation:

BME organ donation

(n=15)

• 13% immediately signed register

• numbers on organ donation Post event

• a further 12% showed ‘strong

register.

questionnaires with inclination’

attendees (n=800)

• 18% wanted more time to

Interviews (n=54)

‘think about it’.

Interviews revealed non-registered

due to religious consideration but

need for BME organ registration

widely accepted.

TNS-BMRB[17]

Health promotion: Sexual health

Multi-media campaign: Worth talking about

To measure awareness of:

• Chlamydia and

contraceptive choice

• message take-out and

reactions to it;

• impact on attitudes, behaviour and actions.

Non randomised:

Before and after study

with 700+ CYP and

300+ parents

• Overall no change in awareness

pre and post campaign, although

increased awareness among

parents.

• Already high levels of sex and

relationship advertising,

although that were aware of

the campaign had levels of

recall of messages. However,

over two fifths of CYP aged

16-24 interviewed felt that the

campaign was not relevant to

them.

Gobin et al.[16]

Health promotion: Sexual health

promotion

Multi-media campaign: Worth talking about

Increase uptake of

Chlamydia screening among 15–24 year olds

Non randomised:

Interrupted time series

analysis of 1,555,139

records

• No overall increased uptake of

testing, but increased testing of

men and Asian groups.

• However, the increases in

testing in these groups were not

sustained after the campaign.

12

2.5 Effectiveness of awareness raising models

Assessing the effectiveness of different models of awareness raising should be approached

with caution due to the variety of topics identified and use of diverse evaluation designs.

Having said this, the evidence presented suggests that awareness-raising techniques appear

to have differential impact on different groups, with some methods such as outreach via

community events providing valuable data that is relevant the current review.

Evidence from multi-media campaigns suggest a mixed picture of effectiveness. Campaigns

to increase awareness of chlamydia testing found no overall increase in uptake of testing,

although there was increased testing of men and people of Asian ethnicity; an increase

that was not sustained following cessation of the campaign[16]. Interviews with children,

young people pre and post campaign showed no difference in advertising awareness, with

a high proportion of respondents already aware of advertising or publicity about sex and

relationships generally. Among parents, awareness was increased significantly (from 57%

to 81% post campaign) including high levels taking or intending to take action as a result of

seeing or hearing the advertising. However, among the core target of 16-24s, over two fifths

felt the advertising was not relevant for them[17]. Gobin et al. suggest that this may explain

the differential effects of the campaign on coverage and positivity in the various sociodemographic groups[16].

The impact of pre-existing knowledge and differences between population groups of

campaign awareness was also observed in the Scottish Executive’s evaluation of its nonTV, radio and poster child protection campaign. The study highlights that sometimes poster

and radio advertising can be confused with television advertising such as high profile TV

campaigns by the NSPCC. However, non-television campaigns can also reach people. When

shown the advertising, half of respondents in the pilot area recognised some part of the

campaign. Women, those with children present in the household and those who had contact

with children at work were all more likely to recognise some aspect of the campaign. The

strongest spontaneously mentioned message was to be observant and look out for children

at risk and to be aware of child abuse and neglect[35].

The evaluation’s wider study of attitudes toward child protection issues showed that all

adults in Scotland (97%) agreed that everyone had a responsibility to help protect children

and young people, with the majority agreeing that it was difficult to know whether a child or

young person may be at risk of, or suffering from, neglect or abuse. Four-fifths (80%) agreed

that if they had concerns that a child or young person was at risk of neglect or abuse they

would know who to contact. However, those who had seen the campaign, were less likely

than other respondents to know who to contact. The campaign had made people reassess

what they thought they knew about who to contact if they believed that a child was at risk

of neglect or abuse. The authors note that further qualitative research would be needed to

explore these issues in more depth, in particular to explore how people would react to real

life child protection situations[35].

13

In order to assess the effectiveness of the implementation of Sure Start, national surveys

were conducted and supplemented by case study data. Data from the National Survey

(2001, 2002) showed that a majority of SSLPs were implementing a wide range of strategies

for promoting programme activities. On average, programmes were using 15 different

methods to ‘get the word out’, with the most popular being home visiting schemes, written

publicity in public places (e.g. libraries) and door-to- door leafleting as well as social events

and parent networking[9]. Authors conclude that all programmes had made considerable

efforts to publicise the planned programme with evidence that partnerships in the later

rounds — 3 and 4 — had learned from the experience of earlier rounds that community

events with entertainment and publicity, were an effective way to raise awareness[7].

However, challenges remained in reaching all families with children under 4 years, with

three quarters of all SSLP managers recognising that their programme was as yet to reach

the whole target community[8]. Of families seen, three quarters of parents felt SSLP well

advertised but just under ¼ felt that there was a lack of information. On-going outreach

was considered key to securing both initial access to families as well as their continuous

engagement. Formal outreach via referrals from their home visitor (e.g. midwife, health

visitor or family support worker) appeared to be appreciated by families. While informal ‘one

off’ community events, such as ‘fun days’ (e.g. Easter egg hunts, ‘balloon days’, picnics,

Christmas parties and summer ‘beach’ parties) were also popular with families and as a

way to make contact with hard-to- reach groups. Such events afforded parents who had not

previously heard of or used Sure Start, an opportunity to see how it worked in an informal

setting, ‘no strings attached’ setting[9].

The ‘standard’ methods adopted by SSLPs to attract parents who may have been more

easily engaged by the programme were supplemented by activities targeted at ‘hard-toreach’ groups. This task was complicated by difficulties in defining which groups were ‘hardto-reach’. While the general identity of these groups could be predicted on a national basis,

in reality, their identity, prevalence and location varied from SSLP to SSLP. Such groups

included: parents/carers with drug and/or alcohol problems; families experiencing some form

of domestic violence; families with children who have special needs; asylum seekers and

refugees; mothers experiencing post-natal depression; fathers/male carers; families with

special cultural requirements; and teenage parents. Implementation data showed that some

groups were more difficult to reach than others and needed extra encouragement to access

services, including fathers and families from minority ethnic groups.

Low levels of involvement of fathers/male carers meant many SSLPs made considerable

effort to encourage their participation. NESS’s study on the nature and extent of men’s and

fathers’ involvement in Sure Start identified fathers’ preference for fun and active sessions

over discussion-based ones with staff indicating it was easier to involve fathers in outdoor,

active, fun day-type activities rather than in indoor sessions with children or in sessions

related to parenting skills[5].

14

Addressing the needs of minority ethnic groups posed similar challenges. Some

programmes appointed inclusion workers with direct responsibility for targeting specific

populations. Language was one issue that SSLPs addressed, with most programmes

providing interpreters as needed, particularly where there was a ‘critical mass’ of specific

population groups e.g. such as people who spoke Urdu or Bengali. In other programmes,

however, diversity of languages was such that engaging a variety of interpreters was not

feasible to fund with relatives used to facilitate communication[11].

Engaging creatively with minority ethnic groups extended beyond language. In one SSLP,

the community development worker established links with the local mosque to encourage

use of Sure Start activities. This link was developed following recognition that women from

this particular ethnic minority required approval from their husbands and/or mothers-in-law

to take up activities. In addition, mothers-in-law as key players within family life within this

ethnic group were also encouraged to make use of SSLP services[9].

Outreach was also a feature of awareness raising activities designed to increase organ

donor registration among BME groups. Following an awareness-raising event held in a

Church Centre aimed at the local BME community, 30/100 attendees signed up to the organ

donation register. Two more people signed following a TV interview with the organiser of

the event and five more following attendance at a local Expo that the organiser attended.

Those that signed were mostly African and Caribbean reflecting audience attendance;

just six people from Asian communities attended the event. While data is minimal on why

people decided to sign the register, Clarke-Swaby concludes that community events are key

awareness activities that speak directly to communities affected and offer an opportunity to

educate and empower BME people to become organ donors[36].

Evaluation of the Peer Educator project initiated by Kidney Research UK, found that outreach

at community events had significantly increased awareness of organ donation among

attendees[37]. Of the 800 attendees that completed questionnaires, two-thirds (75%) felt

that they had learned more about organ donation, that their attitudes had changed (55%)

and that they felt more able to talk to family about the issue (58%). 13% registered on the

organ

donor register immediately. 12% expressed a strong inclination to do so in the near

future and 18% indicated that they may do so after they had had time to think. However,

virtually no respondents registered subsequently, suggesting that increases in organ donor

registration are most likely to be achieved immediately, with little impact being achieved

after events. Buffin et al. conclude that use of peer educators from similar backgrounds

to event attendees appears to ease discussion of religious and cultural barriers, facilitating

access to events that hitherto may have been inaccessible[37].

15

3 F

actors promoting and hindering the

success of models

Understanding the factors that promote or hinder the success of community awareness

raising is hampered by the type of the data collected. Quantitative evaluation designs can

describe impact on attitudes and behaviour and but provide limited information on why

attitudes and behaviour may have changed due to awareness activities[16, 17, 35]. Even studies

that were qualitative in nature, often did not collect data on what was it was about the

awareness raising activities that encouraged people to change their thinking and act on

the information provided[36]. Nor are the specifics of awareness raising activities always

well described, making it difficult to assess what it is about particular activities that users

liked best[9]. Nevertheless, both NESS and Buffin et al. provide nuanced information on

what works when it comes to awareness raising with specific target populations: men and

minority ethnic groups[5, 11, 37]. These can be grouped as: having clear aims and objectives;

understanding the needs of the target audience; engagement with wider stakeholders; and

use of designated workers to promote awareness and access to services.

3.1 Aims and objectives

Ensuring clear aims and objectives are crucial to awareness raising initiatives. Each model

identified has well articulated aims and objectives, with some targeted at specific population

groups or taking additional steps to increase awareness among ‘harder-to-reach’ groups. In

the child welfare context, fathers are traditionally regarded as a ‘hard-to-reach’ group. Father/

male carer involvement in SSLPs has been a key area of focus for Sure Start policy. SSLPs

have had to make a considerable effort to engage fathers/male carers, as the programmes

themselves have been seen to be predominantly female-orientated and hence off-putting

to men. In addition, the majority of SSLPs inherited very low levels of father-orientated

provision in the form of parenting groups or other services related to child rearing, and

therefore few areas had already developed a ‘culture’ of father involvement[4]. A themed

study on fathers in Sure Start found that programmes with clear aims to engage fathers and

proactive strategies to increase their involvement, reported higher levels of engagement

than programmes where fathers had not been prioritised[5].

3.2 Understanding the needs of the target audience

Community consultation is a requirement of SSLPs as a means to understand the

relationship between individual and family need and use of services. It is not only a

mechanism for parents to suggest ways that their needs can be met but also widely used

an awareness raising strategy to promote the Sure Start initiative itself. Methods included

parent satisfaction surveys, outreach workers such as health visitors consulting parents

during the course of their work, open morning and special consultation events. No one

method worked in isolation, with best results from SSLPs who had a ‘rolling programme’ of

consultation that recognised the different access needs within the community.

Parents were, in general, happy with the level of consultation they received. Many had

attended ‘parent meetings’ feeding back their views and needs, while some parents had

become parent representatives to the Sure Start management board. One parent

16

commented: “I am a parent member on the board and all our ideas and questions are

listened to and answered fully. We are all important to the programme and always being told

this[9]. Fathers were less likely to be involved at board level, however, with engagement

centered around and often limited to certain types of activities[5].

The themed study about fathers in Sure Start identified a recurrent theme in staff interviews,

concerning fathers’ preference for outdoor, active, Funday-type activities rather than in

indoor sessions with children or in sessions related to parenting skills. Alongside other

strategies, such activities were viewed as an effective method of increasing awareness

of Sure Start and led to greater engagement by fathers with services, including promoting

involvement in parent forums and board meetings. For example one programme manager

said: ‘When we run fundays or have big family trips, big events, dads like to get involved

in helping with that... they like to be the ones going up the ladders and putting the posters

up. But they’re not so keen on being the ones who were sat on the floor reading to the

children.’[5]

As Sure Start local programmes often scheduled one-off fun events and trips at weekends

or evenings, fathers’ apparent preference for these types of activities may also be related to

activities being provided outside ‘traditional’ working hours, making them more accessible to

working men. Garbers et al. argue that labeling groups as ‘hard to reach’ can both prioritise

their needs but also be used as means of avoiding and confronting the tasks necessary to

promote awareness and access to services. They state that it is essential that the tasks of

awareness raising and access facilitation are made within the context of parental expectation

and preferences[4].

Understanding the needs and preferences of the target population is also a theme within

the evaluations on increasing organ donation within BME groups. In order to explore

understandings and cultural beliefs around organ donation, Clark-Swaby conducted a focus

group with Black African, Caribbean and Asian participants. Feedback from the focus

group on the lack of awareness of the increased risk of needing a donated organ among

BME groups and severe shortage of BME donors, led to an event held in a local Church

Centre. The event included personal stories from people both donating and receiving an

organ, something that Clark-Swaby argues helped promote ownership of this issue as one

that directly affects BME groups and helped empower participants to sign up to the organ

donation registry[36].

Adopting a grassroots, community networking approach to increasing awareness of the

need for BME organ donors was also seen as central to the success of Kidney Research

UK’s Peer Educator programme. Peer Educators were drawn from the local BME community

and proved resourceful, in terms of using their initiative, networking skills and contacts to

secure more events. Their use of ‘real’ people who had experience of organ donation also

increased the impact of the programme: ‘I had asked a family friend who has had a kidney

transplant last year. A large number of people wanted to talk to her and ask her questions

and she could answer them there and then’ (Peer Educator). Use of a quiz as an ice-breaker

to help promote discussion, was also reported by Peer Educators as an important tool of

engagement[37].

17

3.3 Engaging with wider stakeholders

Working with local community leaders was another method considered crucial to awareness

raising with BME groups. While none of the major religions in the UK expressly prohibits

organ donation, research has shown that some groups, particularly Muslims often feel

uncertain and wished for guidance from religious scholars. Peer Educators confirmed the

importance of engaging with community leaders and recognising their influence on beliefs

and behaviour. One Peer Educator commented that they had been: ‘...working more slowly

with community leaders to get them on board, they may not always be a religious leader but

they will be the person who is coordinating the group, and so work with them, get them on

board, so it is almost like you have to do a presentation to them first, then you have to do it

to the whole group’[37].

3.4 Designated inclusion workers

Designated inclusion workers were reported within the NESS evaluation reports as having

a positive impact on awareness raising and improving access to the services. Garbers et al.

highlight the helpfulness of having of a designated worker specialising in making contact

with and/or addressing the issues of some ‘hard-to-reach’ groups. Across the study areas,

there was considerable variation in the appointment of such dedicated workers. Where

they were not appointed, then an existing staff member might be trained more broadly in

‘general issues’ related to specific ‘hard-to-reach’ or special-needs groups[4]. However, while

such workers could work well to promote access with minority ethnic groups, for example,

their efforts needed to be jointly owned by the team. One social worker commented: ‘ethnic

minority workers are left to “deal” with families from different cultures, rather than more

joint working with team members where inclusion is everyone’s responsibility’[8].

4 Y

oung people, parents and wider

community views on CSE and

CSE awareness raising

For awareness raising activities to have the most effect, it is important to understand

the nature and extent of young peoples’, carers’ and wider community’s awareness of

CSE. By doing so, awareness raising initiatives can be tailored to address any knowledge

gaps or myths. This section presents data on knowledge and awareness of CSE among

young people, parents and wider community. It is limited by lack of research in this area,

undermining an assessment of what works best from the perspective of people who are

targeted by community CSE awareness raising initiatives.

4.1 Parental perspectives awareness on CSE

In Autumn 2013, Parents Against Child Sexual Exploitation (Pace) in partnership with Virtual

College’s Safeguarding Children e-Academy commissioned two YouGov surveys of parents

and professionals. YouGov surveyed 750 parents and 945 professionals made up of 510

teachers, 209 police officers and 226 social workers to assess parental and professional

understanding, experience, opinions and knowledge of CSE in England. There was a

particular focus on the role of parents and the impact of CSE on families[38].

18

Most parents (63%) and professionals (60%) agreed that UK society acknowledges CSE but

it should be more openly discussed. The majority of parents (93%) had heard the term CSE,

with 55% of parents reporting they have heard about CSE from TV. Six out of ten parents

know ‘something’ about CSE and would most likely turn first to the police for support and

advice. While it appears some parents are aware of sexual exploitation, over half (53%) of

professionals think that parents do not understand what CSE is. This professional concern

is supported by the fact that 40% of parents stated that they would not be confident in

recognising the difference between indicators of CSE and normal challenging adolescent

behaviour[38].

Using a prompted list, parents and professionals were asked to identify signs of CSE.

The list included: mood swings; changes in academic performance; receipt of gifts from

unknown sources; self harming; drug and alcohol misuse; going missing from home or

care; and changes in physical appearance. Both parents (70%) and teachers (68%) are more

likely to mention things they would spot more easily such as mood swings and changes in

academic performance than police/social workers. All three groups think that the receipt of

gifts from unknown sources is a key sign that a child is a victim of CSE[38].

Those with more direct experience of CSE, the police and social workers (76%) were much

more likely to mention that drug or alcohol abuse is a key sign of CSE than parents (45%)

and teachers (55%). While only 50% of parents and 57% of teachers identified going

missing from home or care as an indicator of CSE, compared with 74% of police and social

workers. YouGov also conducted online focus groups with one parent commenting: ‘A

change of attitude in the child, the behaviour towards people or situations in particular. They

usually become more withdrawn and burdened, and therefore are less interactive’[38].

Parents and professionals identified low self-esteem or low self-confidence as the most

important factor that places a child at a higher risk of being sexually exploited. Other

factors consistently identified through the OCC’s Inquiry into CSEGG such as ‘loss through

bereavement’ and living in ‘gang-affected neighbourhoods’ were barely recognised by

parents or professionals, prompting the authors to call for further work to address this

discrepancy. Parents and professionals also identified that some types of families were

more likely than others to have children affected by CSE, focusing on low income, poor

educational achievement and lower social status of families as risk factors. While the

authors agree that a chaotic or dysfunctional home environment is associated with CSE,

this is not the case for all families affected and hence, further work is needed to dispel such

myths. However, one myth seems to be almost dispelled with professionals and parents in

strong disagreement with the assertion that sexual exploitation only happens to girls, with

96% of professionals and 95% of parents in disagreement.

19

Parents were open to participating in awareness raising activities, although mothers (76%)

were significantly more likely than fathers (63%) to indicate that they would attend a

presentation on CSE. There is also a relationship between current awareness of the issues

of CSE and gaining further information, with those who are currently more aware (75%)

significantly more likely to indicate they would attend a presentation than those who are

currently less aware (67%). At least 70% of the parents interviewed said they would attend

such a briefing at their child’s school. However, it should be noted that attendance at other

methods of awareness raising such as outreach via community events was not asked in the

survey[38].

4.2 Children and young peoples’ perspectives on CSE

Despite positive messages on increased awareness of CSE among parents and

professionals identified above, the OCC’s Inquiry into CSEGG found that children and

young people remain ‘invisible’ to services. The Inquiry’s final report identified a significant

difference between children and young people’s views of their needs and what would help

them as victims of CSE, and professionals understanding of what would help. In particular,

the Inquiry continued to references to children ‘putting themselves at risk’, rather than the

perpetrators being the risk to children[14].

Understanding what children and young people already know about CSE more generally

and what they would find helpful in terms of awareness raising is problematic. There is no

known research that is equivalent to YouGov’s research survey of parents and professionals

that would help understandings of children and young peoples’ experiences, opinions and

knowledge of CSE, nor what kinds of awareness raising activities they would find most

valuable. This clearly an area that warrants further research. Beckett et al.’s research into

the scale and nature of gang-related sexual violence is revealing insofar that they too, found

a propensity to ‘victim blame’, with young women held responsible for the harm that they

experienced and a resignation among young women that such violence is ‘normal’ and to be

expected. Beckett et al. argue that such responses should be understood within the context

of wider patterns of sexual violence and gender inequality in general society[12, 13].

Resistance to what constitutions sexual violence and resignation that sexual violence is

normal, combined with a lack of faith in services’ ability to protect them from retaliation

and/or respond appropriately, explained young peoples’ low levels of reporting and support

seeking. Nevertheless, interviews with young people affected by gang-related sexual

violence, did identify a desire for more openness about sexual exploitation and that young

people would welcome mentoring and discussion with peers who had experience of sexual

violence. Beckett et al. conclude that further work is needed to promote understanding

of healthy relationships, the concept of consent and the harm caused by rape and sexual

assault, particularly with young men[13]. Like the work with BME groups on improving

understanding of the need for organ donation, use of personal stories and developing

personal relationships with young people, may be a key to increased awareness of CSE and

exploitation more generally.

20

This theme is reflected in work on young peoples’ understanding of online grooming,

with peer education and internet safety training provided by someone that they could

relate to welcomed by UK-based young people[19]. The European Online Grooming Project

commissioned by the European Commission Safer Internet Plus programme and conducted

by a collaboration of European academics found that the word ‘groomer’ was in some cases,

unfamiliar. When definitions were established, descriptions of online groomers tended

to be stereotypical depictions of old, unattractive or ‘sick’ people. The authors argue that

more needs to be done to support young people understand the diverse profile of online

groomers, with such attitudes open to abuse by groomers who can present themselves

attractively[18, 19].

Focus groups with young people in Belgium, Italy and the UK revealed them to be better

informed about the type and style of approach that groomers make, including via chat rooms

and images, identity deception, information seeking and asking to meet. Despite this, the

research identified some key gaps in young peoples’ knowledge and understanding of

online grooming including: limited awareness of how some groomers can scan the online

environment for information before making contact e.g. via Facebook profile pages; no

awareness of the role of mobile phones in the grooming process; and a focus on meetings

as an outcome at the expense of understanding continuation of online abuse via image

collection[19].

The research also found an unwillingness to report inappropriate contact, with young

people preferring to deal with things alone, particularly boys. Girls were more likely to share

their experiences but this tended to with friends rather than parents and professionals.

This seems to be linked with fear of negative sanctions, specifically that home computer

privileges would be revoked. Hence, the authors argue that punitive, fear-based approaches

to cyber-safety are ineffective rather balanced, informative approaches are more likely to

empower and engage young people and encourage disclosure. Parents and carers have

a key role to play in providing compelling, balanced information about online risks but are

struggling with their evolving roles as parents in the face of rapid advancements in digital

technologies[19].

Given differential awareness and responses according to gender, the authors argue that

online safety awareness needs to target girls and boys differently. They also highlight that

some groups of young people are more likely to be vulnerable to online grooming. Such

children and young people have fewer sources of protection against cyber-risks through

family, peers, neighbours and school setting. In addition, they have psychological profiles

likely to attract predators who operate in the digital world. However, authors state that

the mechanisms by which such children may become trapped in abusive online contact,

or the situational constraints on their help-seeking, clearly has other contextual elements

that are not well documented and needs further investigation. This means that training and

intervention packages for vulnerable children and young people and professionals working

with them, have not yet been developed to the same extent as awareness raising and

educational materials with wider, normative populations[19].

21

4.3 Wider community views on CSE

There is no research exploring wider community views on CSE. What exists is neither

evaluated nor formally researched and hence not included for current review. Beckett et al.

in their review of current responses to CSE for the London Councils and London Children’s

Safeguarding Board, found that very few London Boroughs had undertaken awareness

raising with the wider community. Where such activities had been undertaken, they tended

to be in the form of written materials, such as leaflets with only two Boroughs offering these

in a language other than English. No attempt had been made to evaluate CSE awareness

raising initiatives with the wider community[34].

Given lack of information in this area, it is apposite to drawn attention to Community Alliance

Against Sexual Exploitation (CAASE). Set up in response to high profile court cases where

perpetuators have been largely from an Asian/Muslim background, CAASE is led by the

Islamic Society of Britain and HOPE not hate[39]. It adopts a grassroots approach, working

with national and local faith organisations and wider communities to raise awareness of CSE,

encourage reporting and promote services to young people. CAASE aims to develop a crosscommunity response, recognising that the victims and perpetrators of CSE come from all

backgrounds, including producing ‘myth-busting’ material to counter extremist groups who

might attempt to exploit the issue in order to divide communities and stir up hatred[39].

CAASE also produces materials for faith and community leaders, so they can speak out

with knowledge and confidence. Working with CAASE, Together against Grooming (TAG)

has been engaging with Mosques to devote sermons to CSE awareness raising as part of

their campaign, 28/6 KHUTBA AGAINST GROOMING[40]. Christian groups could deliver a

similar message in Churches. While not evaluated, such initiatives underline the importance

of understanding the needs of local communities, as determined by the communities

themselves and adopting awareness raising activities that are sensitive to how best to

engage with people locally.

5 Conclusions and recommendations

While there is growing awareness of CSE, further investigation is needed to understand

what works best to promote awareness of CSE in the community. Awareness raising

is viewed as a key means for preventing CSE, achieving early intervention and support

for children and young people vulnerable to exploitation. To be effective, it is important

to understand the nature and extent of young peoples’, carers’ and wider community’s

awareness of CSE. By doing so, awareness raising initiatives can be tailored to address

any knowledge gaps or myths. YouGov’s survey shows that the majority of parents have at

least heard of CSE via media reporting, but revealed mixed knowledge concerning signs and

indicators and risk factors of vulnerability.

There is limited information on what young people know about CSE and what they would

welcome from awareness raising activities. What knowledge exists comes from young

people affected by sexual exploitation, suggesting that such exploitation is normalised,

reflecting wider structures of sexual violence in society. Nevertheless, young people

22

identified a desire for more openness about sexual exploitation and the development of

trusting relationships and discussion with peers who had experience of sexual violence.

Use of peer relationships to raise awareness of online grooming was also identified within

a major European study of young peoples’ attitudes to online safety. This demonstrated

reluctance to disclosure inappropriate contact online, with young people fearing punitive

action by parents, hence their preference for balanced, informative and peer-based

exchanges of online safety messages.

The lack of evaluated of CSE community awareness raising initiatives, prompted the current

review to explore the wider evaluation literature on approaches to raising awareness of

sensitive social issues. This revealed that awareness raising can be effective, particularly

where work is undertaken to understand and involve the local community and activities

undertaken sensitive to their needs. Awareness raising activities fall into four categories:

multi-media campaigns; outreach via community events; use of Peer educators; and multimodal approaches that include both informal outreach such as Fundays and formalised

outreach via home visiting. Awareness activities appear to have differential impact on

different groups, with women for example, with children in their household more likely to

recognise child protection campaigns. A finding confirmed by YouGov’s survey, whereby

mothers’ reported higher levels of awareness of CSE and a greater desire than fathers to

attend awareness raising activities to learn more information.

The factors that promote effective community awareness raising include: having clear aims

and objectives; understanding the needs of the target audience; engagement with wider

stakeholders; and use of designated workers to promote awareness and access to services.

All models identified have well articulated aims and objectives, with some targeted at

specific population groups or taking additional steps to increase awareness among ‘harderto-reach’ groups. In the child welfare context, fathers are traditionally regarded as a ‘hardto-reach’ group. SSLPs that identified fathers as a priority were more likely to have higher

involvement from fathers, promoted via an understanding of their preference for outdoor,

active, Funday-type activities.

Raising awareness with BME groups was dependent on engagement with local community

leaders and adopting a grass-roots approach to activities. Use of community events to raise

awareness of the need to increase organ donation among BME groups worked well, with

Peer Educators from similar backgrounds to event attendees appearing to ease discussion of

religious and cultural barriers and increasing organ donation registry. Adopting an approach

sensitive to community needs is a central tenant of work undertaken by CAASE. While

unevaluated, such an initiative demonstrates the importance of engaging with faith and

community leaders, highlighting use of trusted sources such as sermons as one method of

sensitive CSE awareness raising.

Understanding effective methods of CSE community awareness raising is in its infancy.

From the perspective of professionals, the main purposes of community awareness raising

are prevention, identification, early intervention and advice and support. There is almost no

information on what children, young people, parents and carers or the wider community

wants from CSE awareness raising. Where CSE awareness raising activities have been

23

undertaken with these groups, it is almost entirely unevaluated. This is a significant gap

in the knowledge base and clearly, an area that warrants further investigation to ensure

future effectiveness of such activities. Nevertheless, evidence from the wider evidence

base on effective approaches to community awareness raising of sensitive social issues,

demonstrates positive impact, particularly where the needs of different groups are

understood and awareness raising strategies targeted accordingly.

Suggested reading

Beckett, H., C. Firmin, P. Hynes and P. J (2013). Tackling Child Sexual Exploitation: A Study of

Current Practice in London. Luton: University of Bedfordshire.

The Scottish Government (2005). Protecting Children and Young People 2005:

Pilot Campaign Evaluation. Retrieved 09.12.13, from http://www.scotland.gov.uk/

Publications/2005/10/11155156/51562.

YouGov (2013). Are parents in the picture? Professional and parental perspectives of child

sexual exploitation. London: YouGov.

Useful websites

The Local Government Association (LGA) have developed a CSE awareness raising resource

that includes a comprehensive round up of materials, such as Barnardo’s jointly produced

guidance on effective responses to CSE and their ‘Spot the Signs’ leaflet for professionals as

well as materials on engaging the wider community, accessible via the following link

http://www.local.gov.uk/children-and-young-people//journal_content/56/10180/3790391/

ARTICLE

Pace and Virtual College’s Safeguarding Children e-Academy has launched an e-learning

course for parents on the signs of CSE which is free to access and can be found at

http://keepthemsafe.safeguardingchildrenea.co.uk

24

References

1 J ago, S., et al., What’s going on to safeguard children and young people from sexual exploitation?

How local partnerships respond to child sexual exploitation. 2011, University of Bedfordshire:

Luton.

2 D

epartment for Education, Tackling child sexual exploitation action plan. 2011.

3 R

utter, D., et al., SCIE systematic research reviews: guidelines (2nd edition), in SCIE Research

resource 1. 2010: London

4 G

arbers, C., et al., Facilitating Access to Services for Children & Families: Lessons from Sure Start

Local Programmes. Child and Family Social Work, 2006. 11(4): p. 287-96.

5 L

loyd, N., M. O’Brien, and C. Lewis, Fathers in Sure Start. 2003: London.

6 N

ational Evaluation of Sure Start, Early Experiences of Implementing Sure Start, in Report 01.

2002: Nottingham.

7 N

ational Evaluation of Sure Start, Getting Sure Start Started, in Report 02. 2002: Nottingham.

8 N