PDF - Florida State University

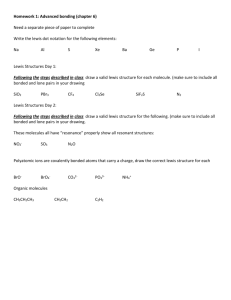

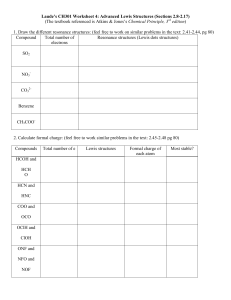

advertisement