Social Skills Training for Teaching Replacement Behaviors

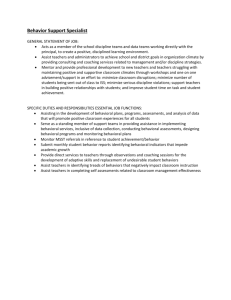

advertisement

Social Skills Training for Teaching Replacement Behaviors: Remediating Acquisition Deficits in At-Risk Students Frank M. Gresham Louisiana State University Mai Bao Van Garden Grove Unified School Disrtict Clayton R. Cook University of California–Riverside ABSTRACT: Social skills training has been recommended as an intervention for students having difficulty establishing meaningful social relationships with peers and teachers in school settings. Several metaanalyses of the relevant literature have shown weak to moderate effects, whereas other syntheses have shown somewhat larger effects. The meta-analyses show that the typical social skills intervention averages 2.5–3.0 hours per week for 10–12 weeks for a total of approximately 30 hours, which may be insufficient to remediate long-standing social skills deficits. The current study identified students who were homogenous on the type of social skills deficit (i.e., acquisition deficits) and provided them with intense (60 hours) social skills training and classroom-based interventions. Students receiving intense social skills instruction showed rather large decreases in competing problem behaviors that were maintained at two-month follow-up and that were socially validated by substantial pretest/ posttest changes in teacher ratings of social skills and competing problem behaviors. Social skills and social competencies are important in students’ development of interpersonal relationships with peers and significant adults. Those who fail to develop adequate social competencies are at risk for a number of negative outcomes, including peer rejection, later manifestations of psychological disorders, dropping out of school, loneliness, criminality, and poor academic performance (Coie & Dodge, 1983; Gresham, 2002; Parker & Asher, 1987). A large body of research accumulated over the past 20 years suggests that a number of at-risk students fail in their social relations with the three most important social agents in their lives—peers, teachers, and parents (Patterson, Reid, & Dishion, 1992; Reid, Patterson, & Snyder, 2002; Walker & Severson, 2002). Many students who are either at risk for or classified as emotionally disturbed in schools under the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act (IDEA 2004) exhibit social competence deficits (Forness & Knitzer, 1992; Gresham, 2002). The current federal Behavioral Disorders, 31 (4), 363–377 BD_31(4).indd 363 definition of emotional disturbance specified in the IDEA includes two criteria that involve social competence difficulties: (1) an inability to build or maintain satisfactory interpersonal relationships with peers and teachers, and (2) the expression of inappropriate behavior or feelings under normal circumstances. It is clear that long-term personal and social adjustment of individuals is based to a large degree on an ability to build and maintain positive interpersonal relationships, skill in establishing peer acceptance, the capacity to form meaningful friendships, and skills that allow for avoidance or termination of negative or destructive relationships with others (Kupersmidt, Coie, & Dodge, 1990; Parker & Asher, 1987; Walker, Ramsey, & Gresham, 2004). Conceptualization of Social Skills Social skills can be conceptualized as a response class made up of topographically August 2006 / 363 9/6/06 7:46:19 AM dissimilar social behaviors. These behaviors can be grouped in same functional response class because they produce the same outcomes or serve the same function for individuals (Johnston & Pennypacker, 1993). For instance, discrete behaviors such as establishing eye contact with others, greeting others verbally, listening to others, and appropriately gaining entry into a peer group can be grouped under the response class of “peer-related social skills” (Walker, Irwin, Noell, & Singer, 1992). These behaviors, although topographically dissimilar, may serve the same function—positive social attention from peers (Gresham, Watson, & Skinner, 2001). Social skills can also be conceptualized from a social validity perspective in which they are defined as specific social behaviors and response classes that predict important social outcomes for students (Gresham, 1986). Using a social validity view, social skills represent a set of competencies that (1) facilitate initiating and maintaining positive social relationships, (2) contribute to peer acceptance and friendship development, (3) result in satisfactory school adjustment, and (4) allow individuals to cope with and adapt to the demands of the social environment. Another important conceptual feature of social skills is the distinction between social skill acquisition and performance deficits. Acquisition deficits can be described as either the absence of knowledge about how to perform a given social skill or difficulty in knowing which social skill is appropriate in specific situations (Gresham, 1981, 2002). Acquisition deficits can also be characterized as “can’t do” problems (i.e., the student cannot perform the social skill under optimal conditions). Performance deficits can be conceptualized as the failure to perform given social skills at acceptable levels even though the student may know how to perform the social skill. These types of social skills deficits are best thought of as “won’t do” problems (i.e., the student knows what to do but does not want to perform the social skill). Another feature in conceptualizing social skill deficits is the competing problem behavior dimension (Gresham & Elliott, 1990). Competing problem behaviors effectively compete with, interfere with, or “block” either the acquisition or the performance of a given social skill. Competing problem behaviors can be broadly classified as either externalizing behavior patterns (e.g., noncompliance, aggression, or coercive behaviors) or internalizing behavior patterns (e.g., social withdrawal, depression, 364 / August 2006 BD_31(4).indd 364 or anxiety) (see Achenbach & McConaughy, 1987). For example, a student with a history of noncompliant, oppositional, and coercive behavior may never learn “prosocial” behavioral alternatives such as sharing, cooperation, and self-control because of the absence of opportunities caused by the competing function of these aversive behaviors (Eddy, Reid, & Curry, 2002). Similarly, a student with a history of social anxiety, social withdrawal, and shyness may never learn appropriate social behaviors because of withdrawal from the peer group and the absence of opportunities for learning peer-related social skills. One aspect of social skills conceptualization that has been often overlooked is the effectiveness of teaching positive replacement behaviors to overcome competing behaviors. Maag (2005) suggested that replacement behavior training (RBT) might solve many of the problems described in the social skills training literature, such as poor generalization and maintenance, modest effect sizes, and social invalidity of target behavior selection. RBT is based on the premise of functional analysis of behavior. That is, the goal in RBT is to identify a prosocial behavior that serves the same function as the inappropriate behavior. For example, a student engages in disruptive behavior in a classroom and a functional behavioral assessment determines that the function of that behavior is social attention from peers and the teacher. A RBT approach would identify a prosocial behavioral alternative such as work completion and paying attention to the teacher that would result in peer and teacher social attention (i.e., that would serve the same function). Elliott and Gresham (1991) recommended similar strategies based on differential reinforcement techniques to decrease occurrences of competing problem behaviors and to increase occurrences of prosocial behaviors. Finally, several meta-analytic reviews of the social skills training (SST) literature have shown weak to moderate effect sizes (Gresham, Cook, Crews, & Kern, 2004). Metaanalyses of research conducted with students with or at risk for emotional and behavioral disorders (Mathur, Kavale, Quinn, Forness, & Rutherford, 1998; Quinn, Kavale, Mathur, Rutherford, & Forness, 1999) and learning disabilities (Forness & Kavale, 1999) showed weak effect sizes. These small effect sizes, however, are inconsistent with other metaanalytic reviews that show much larger effects (Mdn D = .60) (see Gresham et al., 2004). These Behavioral Disorders, 31 (4), 363–377 9/6/06 7:46:19 AM differences in effect sizes notwithstanding, one explanation for weak effect sizes produced in some SST studies may be explained in part by the relatively low intensity of many SST protocols. For example, the studies in the meta-analyses conducted by Mathur et al. (1998), Forness and Kavale (1999), and Quinn et al. (1999) averaged only 30 hours for the entire SST program. This corresponds to approximately 2.5 to 3.0 hours of SST per week for 10 to 12 weeks. It may well be that 30 hours of social skills instruction may not be sufficiently intense to remediate many students’ social skills deficits. Purpose of Present Study The purpose of the present study was threefold. First, we identified a group of students who were homogenous on the type of social skills deficit exhibited. Specifically, this study targeted a group of students with social skill acquisition deficits and involved giving those students direct instruction in social skills in a small group setting. Second, we investigated the effects of a high-intensity SST intervention. SST intensity was investigated because prior SST research using 30 hours of training has produced modest effect sizes (Gresham et al., 2004; Mathur et al., 1998). Third, we evaluated the effects of differential reinforcement of other behavior (DRO) delivered in the classroom on generalization and maintenance of intervention effects across settings and over time and on students’ standing on socially valid measures of social skills and problem behaviors. Method Participants and Setting Participants were four students from a large suburban southern California school district. These four students received 60 hours of social skills training over 20 weeks (3 hours per week). Kev was a 7-year-old boy in the second grade. He did not have a history of referral to school study teams or special education, but his teacher indicated that he had substantial difficulties in interpersonal relationships with peers. Laurie was a 6-year-old girl enrolled in first grade. Her teacher stated that she had difficulties making friends and joining peer playgroups at recess. Debbie was a 7-year-old girl in the second grade; her teacher indicated that she had difficulty with impulsivity and Behavioral Disorders, 31 (4), 363–377 BD_31(4).indd 365 inattention. During the study, Debbie was taking 18 mg of Concerta for attention deficit/ hyperactivity disorder. Nate was a 7-year-old second grader. His teacher noted that he had difficulty in temper control and aggressive behavior with peers. The school had universal interventions in place for the entire school population based on a positive behavioral support plan. Specifically, the school had clear rules and objectives for appropriate behaviors (e.g., “Be nice to others,” “Help others,” “Be safe”). Specific examples of each of these behavior classes were posted throughout the school, and students’ occurrences of these behaviors were reinforced using a lottery system. In the lottery, students received a ticket that could be turned into the office for a drawing at the end of the week. The more tickets a student earned, the greater the chance that student had of “winning” the lottery. Reinforcers in the lottery included free time, access to computers, and opportunities to talk/play with friends. School rule infractions resulted in response cost procedures such as loss of recess time, loss of points in class, or a note sent home to parents. T A G Selection Procedures D I s The four participants were between 6 and 8 years of age and were at risk for developing emotional and behavioral disorders. A multiple gating procedure similar to that used by Walker and Severson (1990) was used. First, their general education teachers nominated students during the first month of the new school year. Teacher nominations were based on clear operational definitions of problem behaviors exhibited by students often identified as being at risk for emotional and behavioral difficulties. Teachers were asked to identify 10 students who exhibited behaviors that most closely fit the definition of social skills problems. Teachers rank-ordered the 10 students according to the severity of behavioral difficulties on a 1 (most severe) to 10 (least severe) scale. The specific definition used by teachers was as follows: Co N M G R D No Some kids often start fights or arguments with other kids. They may hit, kick, pinch, swear, or are aggressive toward other kids. They may also say mean or nasty things to hurt others’ feelings. They may show signs of hyperactivity, impulsivity, inattention, defiance, and/or noncompliance toward others in class or at recess. In the second stage of the identification process, teachers completed two standardized August 2006 / 365 9/6/06 7:46:19 AM measures of social skills and problem behaviors: the Social Skills Rating System (SSRS) (Gresham & Elliott, 1990) and the Critical Events Index (CEI) (Walker & Severson, 1990). Students exhibiting a social skills deficit (Total Social Skills < 85 and Total Problem Behavior > 115) as well a CEI score of 1 or greater passed this second gate. In the third stage, students with social skills acquisition deficits were operationally defined using the SSRS social skills and problem behavior scales as recommended by Gresham and Elliott (1990). Specifically, students were considered having social skills acquisition deficits if they received a rating of 0 on the Frequency dimension, a 1 or 2 rating on the Importance dimension on more than 50% of the 30 items (> 15 items), and a rating of 2 on more than 50% of the problem behavior items (> 9 items) (see Gresham & Elliott, 1990). Table 1 presents the Social Skills and Table 2 presents the Competing Problem Behaviors for the four participants based on the above operational definition procedures. Instrumentation A combination of norm-referenced rating scales/checklists and direct observational data served as instrumentation in the current investigation. These instruments and their psychometric characteristics are described below. Social Skills Rating System-Teacher (SSRST). The SSRS-T (Gresham & Elliott, 1990) is a teacher rating scale measuring three domains: social skills (30 items), problem behaviors (18 items), and academic competence (9 items). The elementary version of the SSRS-T was used in the current investigation; it is a nationally standardized instrument based on a sample of 2,400 elementary age students in grades K–6. The SSRT-T documents the perceived frequency and importance of behaviors influencing students’ social competencies and adaptive functioning at school. It has adequate internal consistency reliability for the Total Social Skills (α = 0.93), Total Problem Behaviors (α = 0.88), and Academic Competence (α = 0.95) scales. Four-week test-retest reliability coefficients for the three scales range from 0.84 to 0.93 with a median stability coefficient of 0.85. The SSRS manual reports a number of studies offering validity evidence for the SSRT-T based on test content, relationships with other measures, and the internal structure of items (Gresham & Elliott, 1990). 366 / August 2006 BD_31(4).indd 366 Critical Events Index (CEI). The CEI is a 33-item behavioral checklist that assesses whether a student has exhibited any of 33 high intensity/low frequency externalizing and/or TABLE 1 Social Skills Controls temper in conflict situations with adults Easily makes transitions from one classroom activity to another Attends to your instruction Invites others to join in activities Makes friends easily Initiates conversations with others Gives compliments to peers Volunteers to help others with classroom tasks Joins ongoing activity of group without being told to do so Ignores peer distractions when doing classwork Appropriately questions rules that may be unfair Compromises in conflict situations by changing own ideas to reach agreement Introduces him/herself to new people without being told Responds appropriately to teasing by peers Responds appropriately when pushed or hit by other children TABLE 2 Competing Problem Behaviors Interrupts conversations of others Disturbs ongoing activities Argues with others Gets angry easily Talks back to adults when corrected Has temper tantrums Acts impulsively Fidgets/moves excessively Easily distracted Fights with others Threatens or bullies others Doesn’t listen to what others say Behavioral Disorders, 31 (4), 363–377 9/6/06 7:46:20 AM internalizing behavior problems within the past 6 months (Walker & Severson, 1990). The CEI was standardized on 4,500 cases collected from 18 school districts in 8 states. Separate norms are available for males and females, grade levels, internalizing/externalizing students, and nonreferred students. The CEI has extensive reliability and validity evidence. Reliability evidence is expressed in terms of test-retest, internal consistency, and interrater reliabilities. In terms of validity evidence, the CEI correlates with other measures of behavior problems, social skills, and sociometric status and differentiates referred from nonreferred students for emotional and behavioral difficulties (Gresham, Lane, MacMillan, & Bocian, 1999; Gresham, MacMillan, & Bocian, 1996; Gresham, MacMillan, Bocian, Ward, & Forness, 1998). Direct Observation Measures. These measures were used to assess whether SST had an effect on reducing competing problem behaviors. A total of 23 observation sessions per student were conducted during baseline, intervention, and follow-up phases of this investigation. Total Disruptive Behavior (TDB) was defined as a class of behaviors that disturb the classroom ecology and interferes with instruction. These behaviors included being out of seat without permission, not complying with teacher instructions within 10 seconds, making any audible noises or vocalizations that disrupt ongoing classroom activities, yelling, cursing, and taking others’ property. Each student was observed for 23 sessions of 15 minutes duration each session. TDB was measured using duration recording in which the elapsed time the student engaged in TDB was recorded. Elapsed time was converted to a percentage by dividing the elapsed time by the duration of the observation session and multiplying by 100. Alone time (AT) was assessed using duration recording in 23, 15-minute observation sessions conducted on the playground. The definition of AT was based on the definition given contained in the Systematic Screening for Behavior Disorders (SSBD) (Walker & Severson, 1990) and was defined as the target student not being within 5 feet of another student, being neither socially involved nor socially engaged, and not participating in game or structured activity with other students. Examples included sitting, standing, shooting baskets, kicking balls off walls, and so forth. A student engaged in selftalk (i.e., verbal behavior not directed toward anyone else) would be coded as AT. AT was calculated by recording the elapsed time the Behavioral Disorders, 31 (4), 363–377 BD_31(4).indd 367 student was alone, dividing that number by the duration of the observation session (15 minutes), and multiplying by 100. This procedure yielded a percentage of time the student spent alone on the playground. Negative social interaction (NSI) was also based on the definition contained in the SSBD (Walker & Severson, 1990) and was assessed using duration recording in 23, 15minute observation sessions. NSI was defined as the student engaging in behaviors such as biting others, hitting others, pinching, cursing, or verbally or physically threatening other students. NSI was calculated by recording the duration of time the student met the definition of the behavior, dividing this number by the duration of the observation session (15 minutes), and multiplying by 100. This yielded the percentage of time the target student engaged in NSI on the playground. Interobserver Agreement Two school aides who were blind as to the specific purposes of the investigation served as observers. Before the onset of the observation procedures, the aides were trained in the operational definitions of behavior and how to use duration recording. Observers met for four 1-hour sessions that included the following topics: (a) a discussion of the operational definitions of behavior, (b) direct training on the use of duration recording, and (c) directed practice on using the observation protocol on simulated cases. A random sample of 20% of the observation sessions was selected to assess interobserver agreement. Interobserver agreement was estimated using duration agreement in which the shorter duration of behavior was divided by the longer duration of the behavior. This was converted to a percentage by multiplying by 100 (shorter duration/longer duration × 100). Interobserver agreement estimates ranged from 84% to 95%, with a median interobserver agreement of 90%. Experimental Design The experimental design consisted of 4 ABAB designs (1 design for each of the 4 participants). Each design consisted of 2 baseline and 2 treatment conditions with a 2month follow-up phase. Data were collected during each baseline and intervention phase for 5 sessions each in which each student’s duration of the 3 target behaviors was recorded August 2006 / 367 9/6/06 7:46:20 AM in 15-minute observation sessions. The followup phase consisted of 3 probes on each of the target behaviors collected 2 months after the termination of the intervention. Procedures All students received 20 weeks of social skills instruction specifically using the techniques found in the Social Skills Intervention Guide (SSIG) (Elliott & Gresham, 1991). The second author instructed all four students. Remediating social skills acquisition deficits involved modeling, coaching, and behavioral rehearsal as described in the SSIG. The Appendix gives an example of how each of the social skill acquisition deficits is remediated. The same instructional procedures were used for remediation of all social skill acquisition deficits for all four students. The four students (Kev, Laurie, Debbie, and Nate) received 60 hours of SST. The second author delivered all instruction in a small-group pullout setting as described in the SSIG. Students received two sessions per week for 1.5 hours each session (40 sessions). DRO Procedures In addition to instruction in the pullout setting, the second author provided direct consultation and recommendations to the students’ teachers and parents. After each session, the second author provided a set of explicit instructions regarding the use of differential reinforcement of other behaviors (DRO). Specifically, DRO involved delivering a reinforcer (verbal praise) after an interval of time in which a competing problem behavior did not occur at the end of the interval (Repp & Dietz, 1974). The DRO procedure consisted of four steps: (a) identifying the reinforcer for the competing behavior (e.g., social attention), (b) identifying the reinforcer for appropriate behavior (e.g., social attention in the form of verbal praise), (c) specifying the DRO time interval (i.e., DRO–5 minutes), and (d) eliminating the reinforcer for competing problem behaviors and delivering a reinforcer for appropriate competing behaviors (Miltenberger, 2004). The current investigation used momentary DRO scheduling (as opposed to interval DRO), which constitutes delivering verbal praise at the end of a specified time interval in which the target behavior did not occur. Teachers used a momentary DRO–5 minute 368 / August 2006 BD_31(4).indd 368 schedule of reinforcement (i.e., verbal praise was delivered after 5 minutes elapsed in which inappropriate behavior did not occur at the end of the interval). Using the direct behavioral consultation procedures described by Watson and Robinson (1996), the second author gave the teacher a protocol containing examples of DRO procedures and demonstrated DRO techniques in that teacher’s classroom. The second author also conducted weekly monitoring and consultation sessions with both teachers and parents to provide feedback on students’ progress, discuss treatment integrity data, and suggest modifications in the intervention strategies. Social Skills Training Procedures We used four basic instructional variables to remediate students’ acquisition deficits in a small group setting: direct instruction, rehearsal, feedback/reinforcement, and reductive procedures. Instruction was delivered using verbal (often called coaching) and modeled instruction. Verbal instruction involves using concrete and abstract concepts to teach social skills. Modeled instruction, on the other hand, delivers instruction visually to the learner so that he or she can learn how to combine and sequence the behavioral components of a given social skill. Rehearsal involves the repeated practice of a social skill once it has been learned. Rehearsal or practice leads to more effective and efficient behavioral performances and can take three forms: overt rehearsal, covert rehearsal, and verbal rehearsal (Elliott & Gresham, 1991). Overt behavioral rehearsal was used in the present investigation and involved observable behavioral performances of a social skill after coaching and modeling of a given social skill. Feedback and reinforcement procedures were used to enhance students’ performances of acquired social skills. The feedback given was information on the correspondence between social skill performance and the expected standard of performance. The students received specific information about the quality of social skills exhibited in role-play performances of specific social skills. Reinforcement involves presenting (positive reinforcement) or removing (negative reinforcement) environment events to increase the frequency of social skills. We used only positive reinforcement procedures to facilitate social skills performances. Reductive procedures are designed to reduce or eliminate competing problem Behavioral Disorders, 31 (4), 363–377 9/6/06 7:46:20 AM behaviors that often interfere with the effective teaching social skills. Reductive procedures include techniques such as timeout, response cost, and various forms of differential reinforcement. We used only differential reinforcement and response cost procedures to reduce competing problem behaviors in both the small group and classroom settings. Treatment Integrity Treatment integrity of the pullout group social skills training procedures was evaluated by the instructor’s adherence to the procedures detailed in the SSIG (a manualized treatment protocol) as recommended in the behavior therapy literature (see Eifert, Schulte, Zvolensky, Lejuez, & Lau, 1997). In the present study, treatment integrity was ensured by a definitive description of the SST techniques to be used and specific statements of what operations the instructor is to perform. The SSIG meets both of these criteria for treatment integrity. We assessed treatment integrity of the teachers’ use of DRO and reductive procedures by direct observation of intervention implementation. Using a checklist of all components of given treatment procedures, the same teacher aides who recorded durations of the three target behaviors recorded the percentage of treatment components correctly #BTFMJOF *OUFSWFOUJPO implemented by the teachers. Interobserver agreement estimates were collected randomly for 20% of the observation sessions. Percent agreement was calculated by dividing the number of agreements by the number of agreements + disagreements and multiplying by 100. Percent agreement averaged approximately 82% for the classroom-based intervention implementation. Intervention integrity estimates ranged from 65% to 86% (M = 74.17%) for Kev, Laurie, Debbie, and Nate. Results Figures 1–4 depict target behavior durations for Kev, Laurie, Debbie, and Nate. Laurie, Debbie, and Nate showed substantial decreases in AT on the playground compared to Kev. Effect size estimates for each of the target behaviors were quantified using the percentage of nonoverlapping data points (PND) between baseline and treatment phases (Mastropieri & Scruggs, 1985-86). Although PND has some methodological drawbacks (Faith, Allison, & Gorman, 1997), outcomes were expressed using this metric to be consistent with the single subject meta-analysis provided by Mathur et al. (1998). PND is computed using the number of treatment data points below the lowest baseline data point (for target behaviors one is trying to #BTFMJOF *OUFSWFOUJPO 'PMMPXVQ 5%# %VSBUJPO1FSDFOUBHFT /4* "5 ,FW 4FTTJPOT Figure 1. Duration times for TDB, NSI, and AT for Kev. Behavioral Disorders, 31 (4), 363–377 BD_31(4).indd 369 August 2006 / 369 9/6/06 7:46:21 AM #BTFMJOF *OUFSWFOUJPO #BTFMJOF *OUFSWFOUJPO 'PMMPXVQ %VSBUJPO1FSDFOUBHFT "5 5%# /4* -BVSJF 4FTTJPOT Figure 2. Duration times for TDB, NSI, and AT for Laurie. #BTFMJOF *OUFSWFOUJPO #BTFMJOF *OUFSWFOUJPO 'PMMPXVQ %VSBUJPO1FSDFOUBHFT "5 5%# /4* %FCCJF 4FTTJPOT Figure 3. Duration times for TDB, NSI, and AT for Debbie. 370 / August 2006 BD_31(4).indd 370 Behavioral Disorders, 31 (4), 363–377 9/6/06 7:46:21 AM decrease). For example, if 8 of 10 data points in the two treatment phases are below the lowest data point in the first baseline phase, then PND would be 80%. Table 3 shows PND estimates for the four students. All four students showed substantial PND estimates across the three target behaviors (M = 76.23%). Nate and Kev showed the largest PND for TDB (100% and 92.31%, respectively) and AT (100% and 76.92%, respectively). SST was less effective for Laurie’s NSI (46.15%) and for Debbie’s AT (46.15%). Table 3 also depicts treatment integrity estimates for the four students, which ranged from 65.42 to 85.58% (M = 74.17%). Treatment integrity was very good for Kev (79.12%) and Nate (85.58%) but was substantially lower for Laurie (68.75%) and Debbie (65.42%). Table 4 shows the combined social validation data as measured by the SSRS-T for Kev, Laurie, Nate, and Debbie. The four students moved from a pretest mean of 78.25 to a posttest mean of 101.25 on Total Social Skills, or from the 7th to approximately the 50th percentile. For Total Problem Behaviors, the students moved from a pretest mean of 124 to a posttest mean of 102.75, or from the 95th to the 58th percentile. SST did not appear to #BTFMJOF *OUFSWFOUJPO TABLE 3 Percent Nonoverlapping Data Points and Treatment Integrity PND (%) Treatment Integrity (%) Kev 79.12 TDB 92.31 NSI 84.62 AT 76.92 Laurie 68.75 TDB 76.92 NSI 46.15 AT 84.62 Debbie 65.42 TDB 61.54 NSI 84.62 AT 46.15 Nate 85.58 TDB 100 NSI 61.54 AT 100 M #BTFMJOF 76.23 74.17 *OUFSWFOUJPO 'PMMPXVQ %VSBUJPO1FSDFOUBHFT /BUF 4FTTJPOT Figure 4. Duration times for TDB, NSI, and AT for Nate. Behavioral Disorders, 31 (4), 363–377 BD_31(4).indd 371 August 2006 / 371 9/6/06 7:46:22 AM TABLE 4 Social Validation Measures: Social Skills Rating System—Teacher M Total Social Skills Pretest SD Posttest SD 78.25 9.85 101.25 10.66 Total Problem Behaviors 124.00 11.33 102.75 12.42 Academic Competence 85.00 12.33 89.25 11.38 have an appreciable effect on the students’ Academic Competence ratings on the SSRS-T. Follow-up probes collected two months after the termination of SST showed maintenance effects on some target behaviors. All students showed similar maintenance effects for TDB two months after intervention. Kev, Debbie, and Nate showed good maintenance for NSI at follow-up and all four students showed adequate maintenance for AT during the follow-up probes. Discussion The current findings indicate that students receiving a relatively intense SST demonstrate rather large decreases in competing problem behaviors and improvement on social validation measures. Sixty hours of SST also produced large changes in NSI for Kev and Debbie, a moderate effect for Nate, and a relatively small effect for Laurie. Large effects for TDB in the classroom were observed for Kev, Laurie, and Nate, and moderate effect for this behavior was shown for Debbie. Three of the four students showed large decreases in AT on the playground (Kev, Laurie, and Nate). These results suggest that a higher intensity or “dosage” of SST than has been reported in the literature produces larger effects on target behaviors and social validation measures than lower intensity SST. This “dose effect” would seem to argue for simply providing more SST to achieve positive outcomes. Treatment integrity levels, however, may also moderate these findings. The effect of treatment integrity on SST outcomes has not been studied extensively in the literature. Three meta-analyses of the SST literature have shown relatively weak effects for SST with students (Forness & Kavale, 1999; Mathur et al., 1998; Quinn et al., 1999). Mathur et al. (1998) analyzed 64 single-case design studies conducted with students with emotional and behavioral disorders. These students, on average, received 2.5 hours per week of SST for 12 weeks (M = 30 hours). This 372 / August 2006 BD_31(4).indd 372 M synthesis of the 64 single-case studies showed that the PND based on 463 graphs showed a moderate effect of 62%. There is also little evidence in various metaanalyses of the SST literature that interventions were implemented as planned or intended (Gresham et al., 2004; Gresham, Sugai, & Horner, 2001). Given the absence of treatment integrity data in the SST literature, one does not know if a SST program is ineffective because it is a poor treatment or if it would be effective if it were implemented with high integrity. The absence of treatment integrity data in the SST literature does not allow one to draw definitive conclusions about the effects of SST on treatment outcomes. Assessment of treatment integrity should be a high priority in future SST research. Forness and Kavale (1999) conducted a meta-analysis of SST studies with students have specific learning disabilities. These authors analyzed 53 studies involving 2,113 students who received, on average, 3 hours of SST per week for 10 weeks (30 hours of SST). Based on analysis of 328 effect sizes, the mean effect size was 0.21, which is virtually identical to the effect size reported by Quinn et al. (1999). Forness and Kavale (1999), Mathur et al. (1998), and Quinn et al. (1999) concluded that SST has limited empirical support for students with emotional and behavioral disorders and learning disabilities. The results of the current investigation indicated that students receiving approximately twice as much SST than has been reported in the literature show much larger effects (M = 76.23% versus 62.00%, respectively). Additionally, the 4 students in this study moved up by 46 percentile ranks on Total Social Skills and down by 84 percentile ranks on Total Problem Behaviors of the SSRS-T. The current data suggest that doubling the amount of SST from the usual amount (30 hours) produces rather large, socially valid effects. The relatively small effect sizes reported in previous meta-analyses can be explained, Behavioral Disorders, 31 (4), 363–377 9/6/06 7:46:22 AM in part, by the failure of studies to match specific types of social skills deficits to specific intervention strategies. SST typically has four objectives: (a) promoting skills acquisition, (b) enhancing skill performance, (c) removing competing problem behaviors, and (d) facilitating generalization and maintenance (Elliott & Gresham, 1991; Gresham, 1998). Most SST studies reviewed in various metaanalyses deliver an intervention with an almost complete disregard for the types of social skills deficits of students. Most research suggests that there is little systematic attempt to assess whether students actually need to be taught the specific social skills chosen in SST (Forness & Kavale, 1999; Gresham et al., 2001). The current investigation specifically targeted students who demonstrated social skill acquisition deficits using systematic assessment procedures. Recall that in this study we defined acquisition deficits operationally as students receiving a rating of 0 (Never) on the frequency dimension and a rating of 1 (Important) or 2 (Critical) in the importance dimension for 50% or greater of the 30 items on the SSRS-T (15 or more items). Competing problem behaviors were defined as receiving a frequency rating of 2 (Very Often) on 50% or greater (9 or more items) on the Total Problem Behavior scale. The effectiveness of SST may be partially due to matching intervention strategies (modeling, coaching, and behavioral rehearsal) to students’ acquisition deficits. Limitations Four limitations of the current investigation should be noted. One, the second author conducted all SST sessions and the teacher/ parent consultation sessions. Although this controls for the expertise level of the instructor, it limits the external validity of the findings. Future research should replicate the current findings using different instructors to enhance the generalizability of these results. Two, teachers completing the SSRS-T ratings on all students were not blind to the fact that these students were receiving SST. They were not aware, however, of the specific hypotheses of the present study. Three, the current investigation did not conduct a systematic functional behavioral assessment (FBA) to determine the controlling functions of the competing problem behaviors. The classroom-based DRO procedures designed to decrease TDB were implemented without the benefit of an FBA. It would have Behavioral Disorders, 31 (4), 363–377 BD_31(4).indd 373 been advantageous to include a formal descriptive FBA in both the classroom and on the playground to identify the hypothesized functions of the competing problem behaviors. The information from this FBA could have been used to formulate testable hypotheses about predictable antecedent and consequent events occasioning competing problem behaviors (see Maag, 2005). Finally, the SST intervention was a packaged intervention that contained many components (small group SST, DRO, and parent and teacher feedback). As such, it was impossible using the current experimental design to isolate the unique effects of each intervention component. It could have been that the DRO procedures for each student accompanied by performance feedback on its implementation were sufficient to promote large decreases in the competing problem behaviors. Future research should contrast an SST-only intervention with a DRO-based intervention to determine their effects on problem behavior reduction. Despite the above limitations, the present study demonstrated that intense SST and classroom-based DRO interventions implemented with integrity can produce relatively large changes in competing problem behaviors and social validation measures completed by teachers. Moreover, these effects were maintained at 2-month followup. This investigation was one of the few to have systematically classified the specific type of social skill deficit (acquisition deficit) and provide social skills instruction based on that classification. Although much more research needs to be conducted, this study offers guidance into fruitful areas of future social skills intervention research for students with or at risk for emotional and behavioral disorders. REFERENCES Achenbach, T., & McConaughy, S. (1987). Empirically based assessment of child and adolescent psychopathology: Practical applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Coie, J. D., & Dodge, K. A. (1983). Continuities and changes in children’s social status: A five-year longitudinal study. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 29, 261–282. Eddy, J., Reid, J., & Curry, V. (2002). The etiology of youth antisocial behavior, delinquency, violence, and a public health approach to prevention. In M. Shinn, H. Walker, & G. Stoner (Eds.), Interventions for academic and behavior problems II: Preventive and remedial approaches (pp. 27–52). Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists. August 2006 / 373 9/6/06 7:46:22 AM Eifert, G. H., Schulte, D., Zvolensky, J. M., Lejuez, C. W., & Lau, A. W. (1997). Manualized behavior therapy: Merits and challenges. Behavior Therapy, 28, 499–509. Elliott, S. N., & Gresham, F. M. (1991). Social skills intervention guide. Circle Pines, MN: AGS Publishing. Forness, S., & Kavale, K. (1999). Teaching social skills in children with learning disabilities: A meta-analysis of research. Learning Disability Quarterly, 19, 2–13. Forness, S., & Knitzer, J. (1992). A new proposed definition and terminology to replace “serious emotional disturbance” in Individuals With Disabilities Education Act. School Psychology Review, 21, 12–20. Gresham, F. M. (1981). Social skills training with handicapped children: A review. Review of Educational Research, 51, 139–176. Gresham, F. M. (1986). Conceptual issues in the assessment of social competence in children. In P. Strain, M. Guralnick, & H. Walker (Eds.), Children’s social behavior: Development, assessment and modification (pp. 143–179). New York: Academic Press. Gresham, F. M. (1998). Social skills training: Should we raze, remodel, or rebuild? Behavioral Disorders, 24, 19–25. Gresham, F. M. (2002). Teaching social skills to highrisk children and youth: Preventive and remedial strategies. In M. Shinn, H. Walker, & G. Stoner (Eds.), Interventions for academic and behavior problems II: Preventive and remedial strategies (pp. 403–432). Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists. Gresham, F. M., & Elliott, S. N. (1990). Social Skills Rating System. Circle Pines, MN: AGS Publishing. Gresham, F. M., Cook, C. R., Crews, S. D., & Kern, L. (2004). Social skills training for children and youth with emotional and behavioral disorders: Validity considerations and future directions. Behavioral Disorders, 30, 19–33. Gresham, F. M., Lane, K. L., MacMillan, D. L., & Bocian, K. (1999). Social and academic profiles of externalizing and internalizing groups: Risk factors for emotional and behavioral disorders. Behavioral Disorders, 24, 231–241. Gresham, F. M., MacMillan, D. L., & Bocian, K. (1996). “Behavioral earthquakes”: Low frequency, salient behavioral events that differentiate students at-risk for behavioral disorders. Behavioral Disorders, 21, 277–292. Gresham, F. M., MacMillan, D. L., Bocian, K., Ward, S., & Forness, S. (1998). Comorbidity of hyperactivity-impulsivity-inattention + conduct problems: Risk factors in social, affective, and academic domains. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 26, 393–406. Gresham, F. M., Sugai, G., & Horner, R. (2001). Interpreting outcomes of social skills training for students with high-incidence disabilities. 374 / August 2006 BD_31(4).indd 374 Exceptional Children, 67, 331–344. Gresham, F. M., Watson, T. S., & Skinner, C. H. (2001). Functional behavioral assessment: Principles, procedures, and future directions. School Psychology Review, 30, 156–172. Johnston, J., & Pennypacker, H. (1993). Strategies and tactics of behavioral research (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Kupersmidt, J., Coie, J., & Dodge, K. (1990). The role of peer relationships in the development of disorder. In S. Asher & J. Coie (Eds.), Peer rejection in childhood (pp. 274–308). New York: Cambridge University Press. Maag, J. W. (2005). Social skills training for youth with emotional and behavioral disorders and learning disabilities: Problems, conclusions, and suggestions. Exceptionality, 13, 155–172. Mastropieri, M., & Scruggs, T. (1985-86). Early intervention for socially withdrawn children. The Journal of Special Education, 19, 429–441. Mathur, S., Kavale, K., Quinn, M., Forness, S., & Rutherford, R. (1998). Social skills intervention with students with emotional and behavioral problems: A quantitative synthesis of single subject research. Behavioral Disorders, 23, 193– 201. Miltenberger, R. G. (2004). Behavior modification: Principles and procedures (3rd ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning. Parker, J., & Asher, S. (1987). Peer relations and later personal adjustment: Are low-accepted children at-risk? Psychological Bulletin, 102, 357–389. Patterson, G., Reid, J., & Dishion, T. (1992). Antisocial boys: A social interactional approach. Vol. 4. Eugene, OR: Castalia. Quinn, M. M., Kavale, K. A., Mathur, S. R., Rutherford, R. B., & Forness, S. R. (1999). A meta-analysis of social skills interventions for students with emotional and behavioral disorders. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 7, 54–64. Reid, J., Patterson, G., & Snyder, J. (Eds.) (2002). Antisocial behavior in children and adolescents: A developmental analysis and the Oregon Model for Intervention. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Repp, A. C., & Dietz, S. M. (1974). Reducing aggressive and self-injurious behavior of institutionalized retarded children through reinforcement of other behaviors. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 7, 313–325. Walker, H. M., & Severson, H. (1990). Systematic screening for behavioral disorders. Longmont, CO: Sopris West Educational Services. Walker, H. M., & Severson, H. (2002). Developmental prevention of at-risk outcomes for vulnerable antisocial children and youth. In K. Lane, F. M. Gresham, & T. O’Shaughnessy (Eds.), Interventions for children with or at-risk for emotional and behavioral disorders (pp. 177– 194). Boston: Allyn & Bacon. Walker, H. M., Irwin, L., Noell, L., & Singer, G. (1992). A construct score approach to the Behavioral Disorders, 31 (4), 363–377 9/6/06 7:46:23 AM assessment of social competence: Rationale, technological considerations, and anticipated outcomes. Behavior Modification, 16, 448–474. Walker, H. M., Ramsey, E., & Gresham, F. M. (2004). Antisocial behavior in school: Evidence-based practices (2nd ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson/ Wadsworth Learning. Watson, T. S., & Robinson, S. L. (1996). Direct behavioral consultation: An alternative approach to traditional behavioral consultation. School Psychology Quarterly, 11, 141–154. AUTHORS’ NOTE Address all correspondence to Frank M. Gresham, Department of Psychology, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803. E-mail: gresham@lsu.edu. APPENDIX Example of Social Skill Instruction Skill: Compromising in conflict situations by changing own ideas to reach agreement Objective: The student will compromise in conflict situations with others by changing opinions, modifying actions, or offering alternative solutions. Coaching Coaching includes the following ten steps: (a) present a social concept; (b) ask for definitions of the social concept; (c) provide clarification for the group’s definition of the concept; (d) ask for specific behavioral examples of the concept; (e) ask for specific behavioral nonexamples of the concept; (f) elicit potential outcomes for performing the skill and for not performing the skill; (g) generate situations and settings in which the skill would be appropriate, generate situations and settings in which the skill would be inappropriate; (h) use behavioral rehearsal to practice the skill; (i) use specific informational feedback about behavioral rehearsal performances; and (j) based on feedback of the initial behavioral rehearsal, have students replay and practice the skill. 1. Introduce skill and ask questions about it: “Today we are going to talk about compromise. This is a way to get along with others when we disagree with them.” When was the last time you had an argument with one of your classmates? What was the argument about and what did you do? What does the word compromise mean? What are some ways people can compromise? (People can calmly present an opinion; listen to others’ opinions, and so on.) How do people show that they are not willing to compromise? What are some good things that might happen if you compromised in an argument or disagreement with your friends or with your parents? What might happen if you did not compromise with friends or parents? 2. Define the skill and discuss key terms. Skill: Ending disagreements or arguments with others by offering alternative ideas, actions, or suggestions. Key terms: compromise, negotiate, alternatives, listening, opinions. 3. Discuss why the skill is important. Sometimes you can avoid arguments or disagreements by compromising. Many times you can come up with a better solution to a disagreement by compromising and listening to another person’s opinions. A lot of times people will think better of you if you calmly end disagreements rather than yell and scream. Behavioral Disorders, 31 (4), 363–377 BD_31(4).indd 375 August 2006 / 375 9/6/06 7:46:23 AM 4. Identify the following skill steps; have students repeat them. a. Recognize that you are in a conflict situation that has the potential for arguments, yelling, or other conflict behaviors. b. Identify what main source of disagreement is and why the other person(s) is/are upset. c. Listen to what other person(s) is/are saying. d. Calmly present your side and see how the other person(s) react. e. Offer a compromise. f. If the other person(s) accepts/accept your compromise, do the compromise. g. If the other person(s) does/do not accept your compromise, offer another solution or ask the other person(s) for alternative solutions. h. Negotiate alternative solutions to the problem and implement the agreed upon solution. Modeling Using one of the following situations, model and role-play the situation. Modeling includes the following six steps: (a) establish the need to learn the skills; (b) identify the skill components; (c) present the modeling display; (d) rehearse the skill; (e) provide specific feedback on rehearsal; and (f) program for generalization. For negative modeling, respond in one of the following ways: Misidentify the cause of the conflict, refuse to listen to the other person, present your side by yelling and screaming, refuse to offer a compromise, and so on. Modeling/Role Play Situations You are at your friend’s house on Saturday, and the two of you are watching TV. Your friend wants to watch one show and you want to watch another show. Your friend says “It’s my house and we’re watching what I say!” Mary wants to play kickball at recess, but you and Julie want to jump rope. Mary says “We always do what you two want to do! Now it’s my turn to decide what to do!” Your friend wants to play basketball but you want to play baseball. Behavioral Rehearsal Behavioral rehearsal includes the following five steps: (a) describe a role-play situation, select participants, and designate roles for each participant; (b) have participants role-play the social situation and instruct observers to watch the performances of each participant closely; (c) discuss and evaluate the performances in the role-play and provide suggestions for improved performance; (d) ask participants to incorporate feedback suggestions as they rehearse the skill; and (e) select new participants to role-play the same social situation. Ask the students to: a. Define the skill. b. Tell why the skill is important. c. State the skill steps, read them aloud together, and think of cues or prompts to help them remember. Follow Through and Practice 1. Review the skill: Discuss the skill of compromising in the next session and in the end of unit review. 376 / August 2006 BD_31(4).indd 376 Behavioral Disorders, 31 (4), 363–377 9/6/06 7:46:23 AM 2. Assign homework: Encourage students to practice compromising at home with their parents, siblings, and neighborhood friends. Generalization and Maintenance 1. Encourage self-monitoring. Have students monitor for one week the use of compromising at school and at home. Tell students to record at the end of each day the number of times they compromised. Stress that students should record the situation in which they compromised, the way in which they compromised, and the result of their compromise. 2. Assign homework. Invite students to discuss the use of compromise with their parents. Ask them what compromise they have made with their parents and how they went about compromising. Encourage students to give examples. 3. Generate situations Invite students to generate a list of situations in which they could and could not compromise. Try to find examples from history or from current events that show people successfully and unsuccessfully compromising. 4. Discuss newspaper article Bring a newspaper article to the group that describes an example of compromise. Discuss the article and determine ways the people in the article could better compromise. Behavioral Disorders, 31 (4), 363–377 BD_31(4).indd 377 August 2006 / 377 9/6/06 7:46:24 AM