Unlocking the Full Potential of the New Haven Line January 2014

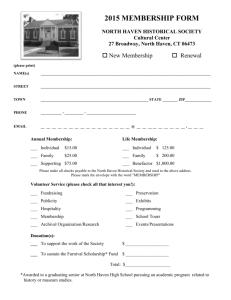

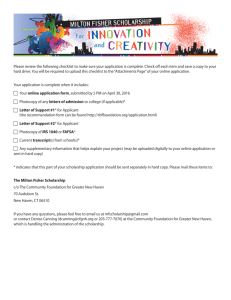

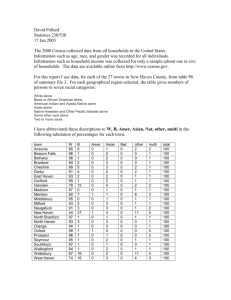

advertisement