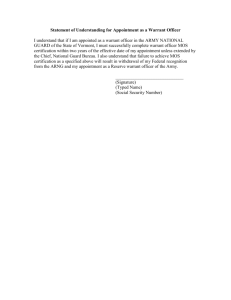

Controverting an Informant's Factual Basis for a Search Warrant

advertisement