Economics for Managers - Asian School of Business

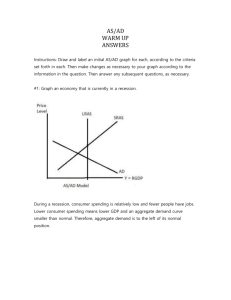

advertisement