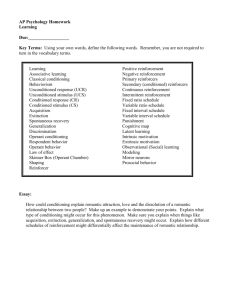

Note format

advertisement

Instrumental Conditioning II The shaping of behavior Conditioned reinforcement Response chaining Biological constraints The Stop-Action Principle l l Guthrie and Horton (1946) puzzle box experiment showed that different actions will be selected, depending on what the cat happened to be doing at the time of reinforcement. The Stop-Action Principle l l Occurrence of reinforcer stops (interrupts) ongoing behavior. Association between situation and behavior ongoing at the time of reinforcement is strengthened. The “Shaping” of Behavior l l l According to the stop-action principle, whatever the organism happens to be doing at the moment of reinforcement tends to be repeated. Natural contingencies between behavior and reinforcement will usually lead to the selection of appropriate behavior. Skinner (1948) demonstrated that accidental pairings of behavioral acts with reinforcement lead to “superstitious” behavior. 1 Shaping by Successive Approximation l l l l Sometimes the act that will produce the reinforcer will naturally occur only rarely, if ever. The subject thus has no opportunity to learn the consequences of that act. To overcome this, the experimenter can begin by reinforcing acts that do occur and which are at least distant approximations to the desired behavior. As these behaviors occur more often, the experimenter changes the criterion for reinforcer delivery toward a closer approximation. This process, called shaping by successive approximation, is continued until the desired act occurs. Skinner’s “Superstition” Experiment Revisited l Staddon and Simmelhag (1971) l l Observed pigeon behavior while delivering grain periodically, independently of behavior. Two classes of behavior were observed: l l l Interim behavior – occurred earlier in the interval between grain deliveries. Terminal behavior – occurred just before grain deliveries. Suggested that these are innate behaviors that tend to occur when likelihood of food is low or high, respectively. Conditioned Reinforcement l l l In classical conditioning, pairing a neutral stimulus with a US transforms the former into a CS: Presenting the CS triggers a CR. Similarly, pairing a stimulus with a reinforcer can transform that stimulus into a conditioned reinforcer – one capable of reinforcing a response. Conditioned reinforcers are also called secondary reinforcers . The natural kind are called primary reinforcers . 2 Demonstrating Conditioned Reinforcement l l l l Briefly present a cue light, followed immediately by the primary reinforcer (e.g., a food pellet). Repeat many times to form an association between the two events. Arrange a contingency between an operant (e.g., a lever-press) and the cue light. The rate of lever-pressing increases. (Note that lever-pressing does not produce the primary reinforcer.) This rate-increase will be only temporary. Can you see why this would be? Conditioned Reinforcement Versus Classical Conditioning l l l In the previous example, a cue light was paired with food across a number of trials. This is a standard classical conditioning procedure; thus we may expect that the cue light will become a classical CS and elicit salivation as a CR. However, because the cue light can be used to reinforce an operant, it is also a conditioned reinforcer. Response Chaining l l l l In response chaining, a series of two or more acts must be completed, in a specific order, before a primary reinforcer will be delivered. The chain begins with the primary reinforcer absent. The first act occurs, and its completion sets the occasion for the next act. The last act in the chain ends with the delivery of the primary reinforcer. Response chains occur naturally, but their properties are easiest to see in what is called a chain schedule. 3 The Chain Schedule l l l l In a chain schedule, two or more links are set up. Each link is identified by a different discriminative stimulus, and arranges a specific contingency between some specified act and some consequent event. In all but the last link, the consequent event is a switch to the next link in the chain. In the last link, the consequent event is the delivery of the primary reinforcer. Example of a Chain Schedule l l l l A hungry pigeon is placed in an operant chamber equipped with a response key and grain magazine. The key turns red as the session begins. First Link: In the presence of the red SD, completing five pecks on the key changes the key color to green. Second Link: In the presence of the green SD, the first peck to occur after 15 seconds have elapsed gives the pigeon 4 seconds of access to grain. After grain-access ends, the key turns red again, signaling a return to the first link. Analysis of the Example Chain Schedule l l l The red key serves as a discriminative stimulus, in the presence of which pecking on the key five times is reinforced. The reinforcement for pecking in the first link is the presentation of the green keylight. Green is a conditioned reinforcer because it is associated with grain delivery. The green keylight also serves as a discriminative stimulus, in the presence of which pecking on the key after a 15-second wait is reinforced by presentation of the primary reinforcer, grain. l Note: because the green keylight continues to be paired with primary reinforcement on each trip through the chain, its ability to reinforce behavior does not extinguish. 4 Biological Constraints on Operant Conditioning l l At one time it was thought that virtually any behavior of which an organism is capable could be shaped up and maintained simply by arranging the appropriate reinforcement contingencies. Two phenomena appear to contradict this belief: l l Instinctive drift, and Autoshaping “The Misbehavior of Organisms” l l l l Breland and Breland (1961) applied operant conditioning principles to train animals for various commercial purposes. At first, the animals acquired the reinforced behaviors and performed well. However, after accumulating more experience in the situation, the animal’s performances broke down as competing behaviors emerged that interfered with the reinforced activities. The new behaviors appeared to be intrusions from the animal’s instinctive repertoire. The Brelands labeled the change toward instinctive forms “instinctive drift .” Analysis of Instinctive Drift l l l Presentation of food begins to produce classical conditioning to available cues preceding food delivery. Classically conditioned CSs then elicit as their CRs behavior instinctively associated with food (e.g., racoons “washing” their food). These instinctive behaviors then interfere with the performance of the operantly conditioned behaviors. 5 Autoshaping l l l Normally, pigeons have to be trained to peck a key, using shaping procedures. Brown and Jenkins (1971) discovered a procedure that would produce key-pecking without the need for manual shaping. Because the process appeared to “shape” up keypecking automatically, the phenomenon was called “autoshaping.” The Autoshaping Procedure l l l Place a pigeon in an operant chamber equipped with a response key. Illuminate the key for 20-second periods every minute or so. Immediately follow the end of each key-illumination with brief access to grain. If the pigeon pecks at the key, immediately present the grain. Analysis of Autoshaping l l l l Pairing of key-illumination with food delivery converts illuminated key into a CS. In hungry pigeons, the sight of food (seeds) instinctively elicits pecking at the seeds. Stimulus substitution: The CR that gets conditioned to the illuminated key is pecking at the key. Because pecks produce access to grain, keypecking is further maintained through operant conditioning. 6 Significance of Autoshaping and Instinctive Drift l l First thought to be violations of conditioning principles. However, now seen as consistent with them. Animals bring into the learning situation a number of instincts that can influence the course of learning. A complete account of the emerging behavior cannot be obtained while ignoring these instincts. 7