Read the study

advertisement

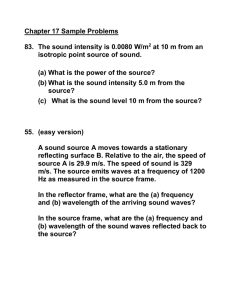

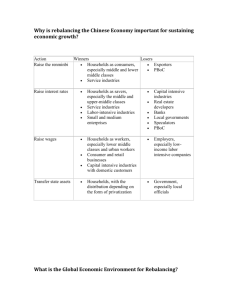

Economy & Rates Negative waves Why don't you knock it off with those negative waves? Why don't you say something righteous and hopeful for a change? (Kelly’s Heroes) February 2016 (figures and charts updated on 10 February, 2016) Bruno Cavalier - Chief Economist, bcavalier@oddo.fr, 33.(0)1.44.51.81.35 Fabien Bossy - Economist, fbossy@oddo.fr, 33.(0)1.44.51.85.38 Tables of forecasts Statistical and chart appendix pages 13-14 pages 16-40 Summary Negative waves • The markets entered 2016 on a pessimistic note. Their mood has deteriorated further. Alongside well known uncertainties (oil, China, Fed), concerns have now emerged that the banking and financial sector will suffer a wave of defaults (by companies or even oil states), leading it to stem the flow of credit to the economy. Economic growth, already fragile or hesitant in many regions, would not withstand this scenario if it materialises. Moving directly from the hypothesis (if…) to the conclusion, the markets’ reaction has been extremely negative in recent weeks. They already seem to take it as read that a sharp slowdown in global growth will occur in the near future, if it is not already underway. In our view, this question has not been settled. • Experience has demonstrated that the financial sector tends to amplify fluctuations in the business cycle. A credit rationing makes recessions more severe, and a credit stimulus facilitates economic recoveries. In this regard, the recent tightening of financial conditions and the severe correction by banking stocks are not good news. A bank lends if it has sufficient capital to cover the associated risks, if it has guaranteed access to liquidity on the markets or from the central bank and if it has risk appetite. At present, only this last parameter has been tangibly affected. At the very least, this may lead to a certain degree of caution in granting new loans. • Besides credit-related questions, the economic cycle also has its own dynamics that hinge on employment, income, productivity, prices and profit margins. No-one can deny that areas of weakness exist in the global economy, but this observation cannot be generalised without ignoring indicators of the real economy. The US economy has passed its mid-cycle, but it is not currently in recession or in a pre-recession state. Employment is robust, the construction sector is catching up fast, consumption is moderating but from a fast pace, economic policy is not restrictive in any way, etc. The big black mark is the crisis in the oil sector. Since its onset 18 months ago, this crisis has had no spillover effects at either the geographical or sectoral levels. There are good reasons to think that the adverse effects of this crisis will fade now that the investment purge is over, while its positive effects will continue to boost the purchasing power of economic agents. Meanwhile, Europe is following the typical trajectory of a recovering economy: strong growth in household consumption, fall in unemployment and the start of an investment pick-up. • One particular concern today is the interest-rate environment, itself largely shaped by monetary policies. After the financial crisis of 2008, central banks, with the best will in the world, conducted unprecedented monetary experiments, such as zero interest rates policies (ZIRP) and quantitative easing. The most radical measure is to set policy rates in negative territory (NIRP). The Bank of Japan has just joined the ECB and other central banks in Europe down this road. For these institutions, negative interest rates are the final tool against deflation since they make it possible to lower real interest rates even when inflation is very low – and, incidentally, they put downward pressure on the currency. In this way, they claim to have restored almost limitless room for manoeuvre. The problem is that there is a qualitative difference, not just a quantitative one, between a positive rate and a negative rate. This may create new frictions at the economic, legal and financial levels. It may also encourage poor capital allocation. In addition, the signalling effect may have the opposite of the intended consequences. Can one be certain of creating conditions conducive to a reflation when government bond yields are negative on maturities of up to 10 or 15 years in some cases? The markets are already emitting enough negative waves. Nobody needs central banks to add to them. Strictement confidentiel 2