The New Fight on the Periphery: Pakistan's Military Role in

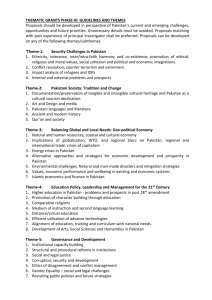

advertisement