Characterizing US Operations in Pakistan

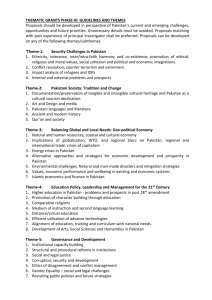

advertisement