China and Cambodia: Patron and Client?

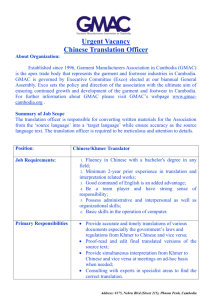

advertisement