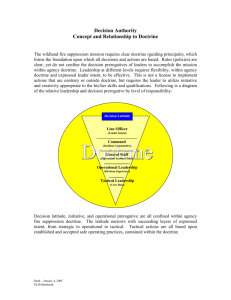

counter-improvised explosive device doctrine review - C

advertisement