PROFESSOR - Muhlenberg College

advertisement

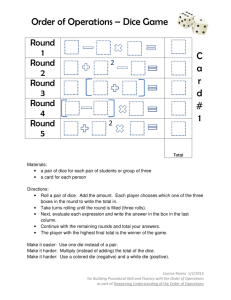

THE Volume 20, Number 4 PROFESSOR April 2006 Use the Power of Groups to Help You Teach By Robert Loser, Northern Virginia Community College rloser@nvcc.edu eading a textbook and listening to a lecture may be useful learning activities, but for most students, when used alone, they are insufficient for long-term retention and transfer of learning. Activities like group work, discussion, and other forms of collaboration have great potential for helping students process new information, ideas, and procedures so that learning is expedited. Here are five research-based reasons for using activities that involve students in class. R individuals would on their own, and the weaker students will learn better strategies from the stronger ones. 3. Knowledge is recalled best when it is learned in the context in which it will be used. Ask students to relate what they are learning to their lives, their work, their families, and society with activities such as role-plays, case studies, and application papers. Once again, groups are going to envision more relevant contexts than individuals are likely to. 1. New knowledge must be anchored to existing knowledge for long-term retention; the more anchors, the better the chances for recall. In a discussion, ask students to compare and contrast new information or ideas with what they already know, or ask them to give examples or analogies. Each elaboration is a potential memory anchor for some learners, and, together, the class will generate many more elaborations than could be thought of individually. Chances are good that someone will suggest a viable elaboration that never crossed your mind. 4. Skills are learned by practice with guidance and immediate feedback. Since you can’t provide immediate feedback to everyone at the same time, enlist your students to help each other in the early learning stages when basic feedback is sufficient, but still vital. Offer clear examples of excellent performance, and then provide students with a rubric for critiquing each other’s work. The greater the number of critiques, the greater the likelihood that the average of the critiques will be reasonably accurate. Besides benefiting from feedback, students are learning something about providing it constructively. 2. Short-term memory can hold only about seven pieces of information at a time. New knowledge must be organized in chunks to fit through this bottleneck during learning and recall. Ask students to organize new information, summarize it, suggest mnemonics for it, and then share their strategies with the class. Again, the class is likely to generate more strategies collectively than 5. Problem-solving expertise requires relevant basic skills and conceptual knowledge, along with being able to decide which basic skills and knowledge to apply in any given situation. Assign problems to heterogeneous groups of five to seven students and facilitate collaboration to solve the problems. Members of the group will have different knowledge and skills to contribute, so the groups will tend to solve problems better than the individual members can on their own. In the process, students will learn knowledge, skills, and strategies from each other, especially if you have them discuss the processes they used. Group strategies help you teach more efficiently by harnessing the parallel processing power of all of the minds in your classroom and open the possibility that you just might learn something from your students! If you are interested in references that explore the research that stands behind these principles, let me recommend two sources. Clark, R., and Mayer, R. (2003). ELearning and the Science of Instruction: Proven Guidelines for Consumers and Designers of Multimedia Learning. San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons. Gagne, E., Yekovich, C., and Yekovich, F. (1993). The Cognitive Psychology of School Learning, Second Edition. New York: HarperCollins. In This Issue Tell Students When They’re Wrong . . . . . .2 Feedback Forms for Peer Assessment in Groups . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3 Improve Thinking: Improve Learning . . . .3 Why Do You Teach? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4 Students and Optimistic Grade Expectations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4 Revising the Freshman Research Assignment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5 Roll the Dice and Students Participate . . . .6 2 THE Tell Students When They’re Wrong PROFESSOR Editor Maryellen Weimer, Ph.D. Penn State Berks Campus P.O. Box 7009, Reading, PA 19610-7009 Phone: 610-396-6170 E-mail: grg@psu.edu Magna Editor Rob Kelly robkelly@magnapubs.com President William Haight whaight@magnapubs.com Publisher David Burns dburns@magnapubs.com Editorial Content Director Bob Bogda bbogda@magnapubs.com Creative Services Manager Mark Manghera Customer Service Manager Mark Beyer For subscription information, contact: Customer Service: 800-433-0499 E-mail: custserv@magnapubs.com Website: www.magnapubs.com Submissions to The Teaching Professor are welcome. When submitting, please keep these guidelines in mind: • We are interested in a wide range of teaching-learning topics. • We are interested in innovative strategies, techniques, and approaches that facilitate learning and in reflective analyses of educational issues of concern. • Write with the understanding that your audience includes faculty in a wide variety of disciplines and in a number of different institutional settings; i.e., what you describe must be relevant to a significant proportion of our audience. • Write directly to the audience, remembering that this is a newsLETTER. • Keep the article short; generally between 2 and 3 double-spaced pages. • If you’d like some initial feedback on a topic you’re considering, you’re welcome to share it electronically with the editor. The Teaching Professor (ISSN 0892-2209) is published monthly, except July and September, by Magna Publications, Inc., 2718 Dryden Drive, Madison, WI 53704. Phone: 608246-3580 or 800-433-0499. Fax: 608-246-3597. E-mail: custserv@magnapubs.com. One-year subscription: (U.S.) $79. Outside the U.S.: $89. Discounts available for multiple subscriptions (please call for price quotes). Periodicals postage paid at Madison, WI. POSTMASTER: send change of address to The Teaching Professor, 2718 Dryden Drive, Madison, WI 53704. Copyright © 2006, Magna Publications, Inc. Back issues cost $20.00 each. A specially-priced collection of previous year’s issues with index and official Teaching Professor 3-ring binder is available for $59.00 plus shipping and handling within the US. We accept MasterCard, VISA, Discover, or American Express. To order, contact Customer Service at 1-800-433-0499. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use, or the internal or personal use of specific clients, is granted by The Teaching Professor for users registered with the Copyright Clearance Center (CCC) Transactional Reporting Service, provided that 50 cents per page is paid directly to CCC, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923; Phone: 978-7508400; www.copyright.com. For organizations that have been granted a photocopy license by CCC, a separate system of payment has been arranged. April 2006 nstructors need to be thoughtful and reflective about those strategies they use when they respond to students’ answers, and this is especially true when the answer given is wrong. Most of us understand that the stakes are high in this case. Students are easily intimidated. Even those not participating can be negatively affected by how an instructor handles incorrect answers. Some current philosophies of education argue against telling students that they are wrong. The thinking here is that students need to figure out for themselves if their answers are right or wrong. Instead of telling them, instructors should guide them to the right answers, possibly through some sort of Socratic dialogue. Robert Ehrlich and Stanley Zoltek (reference below) are strongly in favor of telling students when they are wrong. Their context is science, but the points they make apply to other kinds of knowledge as well. They think that instructors ought to “destigmatize” wrong answers. Mistakes are an inevitable part of learning. They recommend encouraging students to be less afraid of asking “stupid” questions, quoting noted physician Alvan Feinstein, “Ask stupid questions. If you don’t ask, you remain stupid.” They think that putting students under some pressure, while it may undercut their confidence at the moment, in the long run benefits their learning and prepares them for the future. In the world of work, employers have to tell employees when they are mistaken. College classrooms are safer places where students can learn how to handle negative feedback so that it doesn’t traumatize or humiliate them. Always praising answers puts instructors in the awkward position of having to respond to wrong responses indirectly or vaguely. This may result in “considerable student confusion over where the truth lies, or even the misguided belief that correct answers in science may be a matter of opinion.” (p. 10) Finally, they make the point that not using corrective feedback in the classroom I is actually a condescending way to respond to students. If a colleague makes a mistake or says something foolish, he or she would quickly be corrected by other colleagues. It’s something expected among equals. Erlich and Zoltek do understand that how wrong answers are handled is crucial. They make two points: “First, telling students they are wrong must be done in a noninsulting and nonpersonal manner.” (p. 8) It is the answer that is wrong, not the student. “Second, it is not enough to tell students that they are wrong; they must also be told which aspects of their answers are correct, and which aspects are incorrect.” (p. 8) They hold that corrective feedback is not the same as negative feedback. The correction may include many additions, like “Jim, that answer is not correct, but you’re on the right track.” “That answer is close, but not quite right.” “That’s a wrong answer, Susan, but you’ve made a common mistake that all of us can learn from.” They summarize their case for calling wrong answers wrong with this observation: “If you succeed in creating a class environment in which everyone is treated with mutual respect, and being wrong is okay, you should find that students are less fearful of being wrong, and more apt to contribute to class discussion. In this case, students will also be apt to analyze your comments more carefully and may on occasion have the pleasure of correcting you the next time you are wrong!” (p. 10) Reference: Ehrlich, R., and Zoltek, S. (2006). It’s wrong not to tell students when they’re wrong. Journal of College Science Teaching, 35(4), 8–10. The Teaching Professor 3 Feedback Forms for Peer Assessment in Groups any faculty incorporate a peerassessment component in team projects. Because faculty aren’t present when the groups interact and therefore don’t know who’s doing what in the group, they let students provide feedback on the contributions of their group-mates. In addition to giving the teacher accurate information on which to base individual grades, the process gives students the opportunity to learn the value of constructive peer feedback. It’s a skill applicable in many professional contexts. Most faculty have discovered that the quality of peer feedback improves if students use a form that articulates assessment criteria. Otherwise, given a form that asks them to rate or describe the contributions of other members, students tend to avoid giving negative feedback and to fall back on the “everybody contributed equally” mantra. A group of faculty (mostly in engineering) looked at the inter-rater reliability of three short peer-evaluation forms. Interrater reliability is a statistical measure of the extent of agreement among evaluators. It’s an important feature of good assess- M ment instruments. One of the forms used was a single-item instrument without any behavioral anchors or specific assessment criteria, similar to what’s described in the previous paragraph. The second form used a five-point rating scale and asked students to assess team members across 10 categories that included various behaviors, e.g., attended group meetings regularly, contributed to discussions, listened effectively, performed significant tasks, and completed tasks on time. The final form included these kinds of behavioral anchors in its instructions and elaborated descriptions of the rating words (excellent, for example, was defined as “consistently went above and beyond, tutored teammates, carried more than his or her fair share of the load”). However, on this form group members gave peers a single rating assessment. Researchers found that both behaviorally anchored forms had about the same high inter-rater reliability when they were used by four raters in the same group. The value, of course, is the economy of the shorter form. It considerably expedites the grading process, which benefits instructors who may have large classes and homework and other assignments to grade. Researchers also hypothesize that students will complete shorter forms more conscientiously. However, they do recommend using the longer form to accomplish formative goals. They have their students complete it at the end of a first project so that group members can use the feedback to identify areas for improvement. If the feedback indicates that a group has some members who are “hitchhiking” (as in getting a free ride from the group) or “overachieving” (as in dominating and overdirecting the group effort), the instructor meets with those groups to explore better ways to distribute the workload and leadership within the group. All three of the forms tested in this analysis are included in this article. Reference: Ohland, M. W., Layton, R. A., Loughry, M. L., and Yuhasz, A. G. (2005). Effects of behavioral anchors on peer evaluation reliability. Journal of Engineering Education, 94(3), July, 319–325 Improve Thinking: Improve Learning ere’s a list of some practical suggestions taken from a neat, “miniature guide for those who teach on how to improve student learning.” (reference below) The guide was prepared by Richard Paul and Linda Elder, both well-known experts on critical thinking. H • “Focus on fundamental and powerful concepts with high generalizability. Don’t cover more than 50 basic concepts in any one course.” Instead of presenting more new material, spend the time thoroughly analyzing these fundamental concepts. • Keep these basic concepts in the “foreground.” When a new concept is pre- The Teaching Professor sented, weave it into those that students already understand. Show how the whole relates to this new part and how the part relates to the whole. • “Speak less so that they [students] think more.” • “Don’t be a mother robin—chewing up the text for the students and putting it into their beaks through lecture.” The goal instead is to teach students how to read the text for themselves. • Model good critical thinking for students. Think out loud for students; puzzle your way through problems. “Try to think aloud at the level of a good student, not as a speedy professional.” Students will not think they can emu- late the thought process if the problems are too advanced and you work through them too quickly. This miniature guide is part of a “Thinker’s Guide” series that covers 12 topics, including active and cooperative learning, ethical reasoning, how to study and learn, and critical thinking. Some of these guides are written for students as well as faculty. They are reasonably priced, especially for bulk orders. For information about this guide series as well as other resources on critical thinking, visit this website: www.criticalthinking.org. April 2006 4 Why Do You Teach? et’s imagine a “required” professional development activity for faculty: after 20 years of teaching, all college instructors must prepare (we’ll skip the and-submitfor-credit part) an essay that explores the reasons why they teach. The idea for this assignment derives from an essay by Laura B. Soldner (reference below) who found herself restive during a sabbatical year. She couldn’t seem to focus on the textbook she was supposed to be writing but kept revisiting the reasons she chose to teach and exploring how those reasons related to her current professional life. The four reasons Soldner chose to teach and that she discovered continued to motivate her to remain in the profession may not be reasons you’d list, but they illustrate the importance of this kind of introspection, and they might springboard your own reflection. L Sense of discovery—“I am continually struck by the simultaneous nature of teaching and learning. In one instant, I may be the teacher or facilitator of a lesson, discussion, or activity, but I am, at the same moment, a learner who is reconsidering previous knowledge, seeking out new information, or making connections between the two.” (p. 73) Teaching is a profession for those who love to learn. Quest for self-improvement— Soldner writes about the many changes teachers regularly face: favorite texts that go out of print, the increased presence of technology in the lives of students (and their teachers), the declining levels of preparedness of college students, and others. Teachers can bemoan these changes and respond to them with much complaining, or see them as opportunities for growth. Soldner says that her commitment to teaching remains because it provides her with so many opportunities to grow and change. Ability to scaffold development— Soldner is a developmental educator. She works with students on basic reading and writing skills. She explains that the “ability to scaffold development, to provide students with the initial assistance they need and to withdraw that help gradually as they are able to use the skills and strategies independently, is another reason I find teaching so satisfying.” (p. 75) The success of one’s students can bring teachers much satisfaction. Sense of “mattering”—“Developmental literacy educators are often the front line of defense in stemming student attrition. They may be the only ones to have daily instructional and personal interactions with their students.” (p. 77) That makes their work important—to their students, to their institutions, even to our society—and this sense of doing work that makes a difference can be a powerful motivator for all kinds of educators. Perhaps in preparing an essay on “why I teach,” some educators may find that what brought them to education in the beginning no longer sustains them. Those teachers should make a change. For the rest of us, this exercise can be a confirming and motivating experience. It’s easy to forget the reasons or to take them for granted. Preparing an essay like this and then reading it at least once a year would be a beneficial endeavor for most faculty. Reference: Soldner, L. B. (2002–2003). Why I continue to teach: Reflection of a mid-career developmental literacy educator. Journal of College Literacy and Learning, 31, 71–78. Students and Optimistic Grade Expectations sk students what grade they think they’re going to get in a course before the course starts and they’ll tell you that they’re going to do extremely well. Let the course begin, distribute the syllabus, go over course requirements, give students the opportunity to attend several class sessions, and then ask them to predict their grades. Guess what? They are just as optimistic. At least that’s what one group of researchers (reference below) found when they asked 258 undergraduates, most of whom had already completed one year of college. All but two students in this cohort A April 2006 reported that they had read and understood the course syllabus and all but three had been to at least two class meetings. Even so, better than 95 percent of them anticipated a B or better—this despite the fact these students had been told in the course introduction that typically only 50 percent of students in the course earned A’s or B’s. These students’ grade predictions averaged to a 3.6 course GPA when in fact the GPA for the course turned out to be 2.4. A full 70 percent of these students overestimated their final grades, 24 percent accurately predicted them, and a mere 6 percent underestimated them. The researchers analyzed these overestimations in a variety of interesting ways. Most notably but probably not unexpectedly, they found that students who came to the course with lower cumulative GPAs most seriously overestimated their grades for the course. In their discussion of results, the researchers divided this student population into two groups: the informed optimists “who tempered the anticipation of the success they desired with reality” (meaning they expended appropriate effort to PAGE 6 ☛ The Teaching Professor 5 Revising the Freshman Research Assignment By Cara Snyder, Dallas Christian College, TX - csnyder@dallas.edu wo years ago, I said goodbye to the traditional 10-page research paper in my freshman composition classes. My students knew too well that Googling along with cut and paste could produce 10 pages of fluff in no time, with a bibliography of 15 sources. (Who cares how reliable?) It was time for a change. The new assignment consists of five short (about four-page) papers. The student sticks with the same topic through all five papers. Typically, each student has a different topic. The topics are very narrow and reflect the mission of my college, for example, why was stoning the biblical method of execution, or how is “yeast” used in Scripture? I provide a list of suggestions, but students can come up their own topics. One of these papers is due every two weeks (but we’re flexible), and much of our class time is spent in the library, with me finding out about new sources right along with the class as I attempt to answer their questions. As can be seen in the following brief description of the papers, despite the specificity of these topics, the way I’ve reformulated the traditional research paper is applicable to many other topics and content areas. T Paper One—Students begin with a reader-response essay researched using only a primary source. The goal is for the student to find out what this source seems to be saying and showing about the topic. In my case, the primary source is the Bible. Students are limited to versions of the Bible and to complete concordances, and they are expected to study as many passages as possible that pertain to their topics. Similar assignments in other fields could involve whatever the primary literature is, whether creative writing, historical documents, or scientific papers. Paper Two—The second paper requires that students use only sources The Teaching Professor written before 1799. Whether they find these sources online or in hard copy doesn’t matter—the sources just have to be old. In our case, the online library www.ccel.org (Christian Classics Ethereal Library, Calvin College) has made this research easily accessible. I make this the second assignment because this material is the hardest for students to understand, and I find facing the harder challenge early makes the rest of the papers seem easier. My students are usually quite surprised to find that the old guys already have said so much about their topics. Given the difficulty of the material, I grade them on how much they managed to find and how well they organized and presented it rather than how much they may have understood it. I’m hoping for approximately six sources in the works cited. time range, like 1800 to 1980. For this one, I’m hoping for 12 to 15 sources cited but I am happy if I get eight or 10 good ones. Paper Three—Now students are limited to dictionaries, encyclopedias, handbooks, or other reference works. I do allow Wikipedia on this one, but with the stipulation that anything they find in it must be checked against their other sources and that inaccuracies then be submitted to Wikipedia. The goals of this paper are (1) to see how many sources they can find that say the same thing; (2) to find the earliest source saying it; and (3) to check for any differences or added details that have accrued over the years. In this one, they are encouraged to come up with as many citations as possible (I’m hoping for between six and 12). This collection of papers precludes having students integrate all their research into one long paper. I simply do not have the time at that point in the semester to read 20-page papers because I’ve already graded a lot of papers. I do find, though, that I get through the four-page papers much more efficiently and enthusiastically than I do 10-page papers where I’m repeatedly marking the same mistakes. Using this approach gives students more feedback more quickly, and that improves subsequent papers. The greatest advantages I’m finding are that the students really do seem to begin to understand the research process, their topics, and specific kinds of bibliography forms. There is much less mindless Googling and much less plagiarism. So far I’m finding my new system preferable to the traditional approach. Paper Four—In the fourth paper, students turn to the most established works in our field, which are commentaries and books on Scripture since 1800. Again, students may use either print copies or online versions—preferably both—but the bulk of this research should be from print copies on the shelves at the library. My students are generally surprised at this point to discover how much excellent material can be found in books, of all things. I’ve found it useful to designate a Paper Five—Finally, students look at journal articles and Internet sources. Use of relevant electronic indexes for the field (ATLA in our case) is required, but so is as much Googling as they want to do. By this point, the students have become pretty good authorities on their own topics and are better able to judge Internet materials. They do two bibliographies for this paper, one being the works cited, and the other a complete list of all the Internet sources and scholarly articles that might relate, even if they don’t get used. This longer bibliography identifies any unreliable or misleading Internet sources, as well as the best ones. April 2006 6 Roll the Dice and Students Participate By Kurtis J. Swope, U.S. Naval Academy, Annapolis, MD swope@usna.edu recently ran into a former student at a local restaurant. We talked for a few minutes about how his classes were going this semester and what his plans were following graduation. After we talked, it occurred to me that I had heard him speak more during this short conversation than he had during the entire semester he took my course. I was somewhat appalled, being that I’m an instructor who prides himself on engaging (or at least attempting to engage) students in active classroom participation. Here was a student who had done well overall in the course but who had evidently made it through my class with only a modicum of vocal participation. I wonder if your experience is like mine. I find that some students eagerly volunteer answers and often dominate discussions, while others listen, observe, or daydream while their classmates hold forth. I have always been somewhat hesitant to call on inattentive students for fear of embarrassing them or creating an awkward or uncomfortable classroom atmosphere. However, I have also found that those reluctant to volunteer often have quite worthwhile and interesting things to say when called upon. I regularly teach a course in statistics, and a few semesters ago I began using index cards with students’ names to ran- I EXPECTATIONS FROM PAGE 4 achieve the grades they predicted) and uninformed optimists who not only were unable to accurately predict their grades but also seemed to lack “important learning skills and an appreciation of the factors that influence and culminate in course success.” (p. 17) The most interesting part of the discus- April 2006 domly select them for various tasks, such as working homework problems on the board. I used this approach to reinforce the concepts of probability and sample selection, but I found that when I shuffled the cards prior to randomly drawing names, a wave of interest and excitement rippled through the class. Based on this favorable response, I started using the cards during classroom discussions and in other courses as well. Previously some students were justifiably confident that I would not call on them if they did not volunteer, but the cards suddenly made everyone “fair game” every time. It was my wife who suggested that I use dice rolls to simplify and expedite the selection process. She actually found some many-sided dice at a local game store that are perfect for the smaller-sized classes at my institution. However, dice rolls can also be easily adapted to larger class sizes by breaking the section list into several smaller subsections (for example, groups of 10 to 20) and then using two dice rolls—one to pick the subsection and one to pick the student. I found that using the dice rolls frequently to elicit student responses in various contexts has several important advantages: (1) it provides a convenient avenue for looking past the overeager student who participates too frequently; (2) it removes the awkwardness associated with intentionally calling on inattentive students; (3) it generates a sense of anticipation and attention because any student can be called upon at any time; (4) it provides a convenient method of calling on somebody when nobody seems willing to volunteer an answer; and (5) it generates greater variety in student responses. While I do not have any rigorous empirical analysis to prove that frequent use of random selection improves overall learning outcomes, my personal experience has been overwhelmingly positive. Students seem very receptive and goodhumored toward random selection. I am certain that it improves student attention, which is often the greatest challenge. Moreover, most students seem to welcome the dice roll as an alternative to discussions dominated by a few classmates. On the other hand, responses are more frequently wrong or at least not well formulated. But these types of responses actually stimulate greater and deeper discussion because we, as a class, can stop and analyze the responses. I still use “open” discussion quite often, but the dice rolls are very effective at initiating or changing the pace of a discussion. I roll the dice whenever I need to select or assign students to a task. In fact, I now use the dice rolls so often in class that a student this semester asked, “Sir, do you always carry that thing around in your pocket?” I don’t—but maybe I should. I have a feeling it could come in handy unexpectedly, like when I can’t decide which spaghetti sauce to buy. sion of results explores what to do with the uninformed optimists. Should a teacher try to correct their expectations? What happens to students’ motivation when the teacher directly and forcefully tells them that the grades they think they will achieve are highly unlikely? These researchers recognize that having high expectations motivates students. They believe that “uninformed optimists may not benefit from more realistic appraisals as much as they would from skills development.” Instead of trying to discourage grade optimism, teachers ought to make clear what skills are needed to succeed in the course (and the rest of their college courses) and then include opportunities for their development. Reference: Svanum, S., and Bigatti, S. (2006). Grade expectations: Informed or uninformed optimism, or both? Teaching of Psychology, 33(1), 14–18. The Teaching Professor