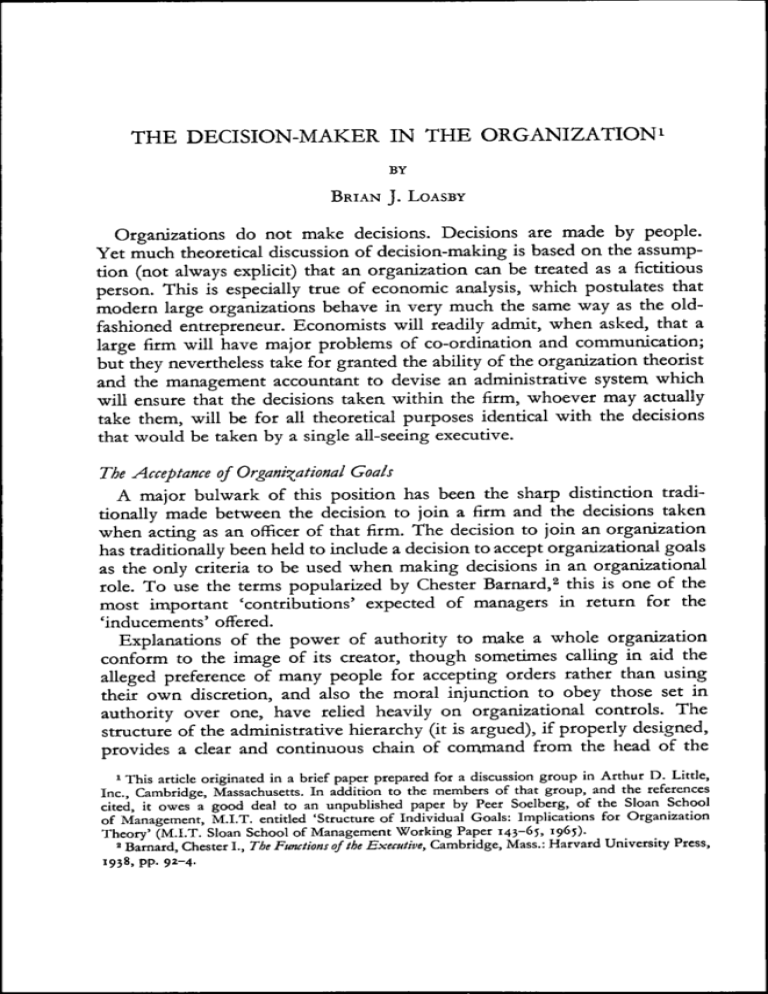

THE DECISION-MAKER IN THE ORGANIZATIONi

advertisement

THE DECISION-MAKER IN THE ORGANIZATIONi BY BRIAN J. LOASBY Organi2adons do not make decisions. Decisions are made by people. Yet much theoretical discussion of decision-making is based on the assumption (not always explicit) that an organizadon can be treated as a ficddous person. This is especially true of economic analysis, which postulates that modern large organizadons behave in very much the same way as the oldfashioned entrepreneur. Economists will readily admit, when asked, that a large firm will have major problems of co-ordination and communicadon; but they nevertheless take for granted the ability of the organization theorist and the management accountant to devise an administrative system which will ensure that the decisions taken within the firm, whoever may actually take them, will be for all theoredcal purposes idendcal with the decisions that would be taken by a single all-seeing executive. The Acceptance of Orgamt(ational Goals A major bulwark of this posidon has been the sharp disdncdon tradidonally made between the decision to join a firm and the decisions taken when acting as an officer of that firm. The decision to join an organization has traditionally been held to include a decision to accept organizadonal goals as the only criteria to be used when making dedsions in an organizational role. To use the terms popularized by Chester Barnard, ^ this is one of the most important 'contribudons' expected of managers in return for the 'inducements' offered. Explanadons of the power of authority to make a whole organizadon conform to the image of its creator, though sometimes calling in aid the alleged preference of many people for accepdng orders rather than using their own discredon, and also the moral injunction to obey those set in authority over one, have relied heavily on organizational controls. The structure of the administradve hierarchy (it is argued), if properly designed, provides a clear and continuous chain of command from the head of the 1 This article originated in a brief papet prepared for a discussion group in Arthur D. Little, Inc., Cambridge, Massachusetts. In addition to the members of that group, and the references cited, it owes a good deal to an unpublished paper by Peer Soelberg, of the Sloan School of Management, M.I.T. entitled 'Structure of Individual Goals: Implications for Organization Theory' (M.I.T. Sloan School of Management Working Paper 143-65, 1965)2 Barnard, Chester I., The Functions of the Executive, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1938, PP- 92-4. THE DECISION-MAKER IN THE ORGANIZATION 353 organization to the lowliest dedsion-maker, and thus ensures that the wishes of the former are understood throughout; and a wide variety of sancdons, ranging from mild disapproval to (in military organizadons) death affords the means to enforce obedience to these wishes. Within the last ten years, the serious defidendes in both of these explanations (in terms of cash incendves or the sancdons of authority) have begun to be realized. The first of these deficiencies is a difficulty with the implications of 'authority'. This difficulty can be explained by drawing an analogy between the two pairs of concepts 'authority — independence' and 'monopoly — perfect compedtion'. In a state of perfect compedtion every unit in the market is completely independent of every other unit: none has any control over price. Unfortunately, monopoly is not the precise andthesis of perfect compeddon. If it were, a 'perfect monopolist' would have absolute control over price; but such absolute control (implying a completely inelastic demand) is not possible. A substandal obstacle to the measurement of 'degrees of monopoly' has been the absence of any unique relationship between the propordon of the total supply of a commodity in the hands of a single producer and his ability to influence its price. It is possible for a firm with a large share of the market to be nevertheless faced with a highly elasdc demand for its product. Monopoly status is not the same as monopoly power. That power depends on the alternative means open to consumers for sadsfying their wants (including their ability and willingness to do without the monopolist's commodity altogether) and also upon the possible consequences (such as legisladon, counter-acdon by customers, or the emergence of a new compedtor) which may follow too ruthless an exerdse of the power which the monopolist does possess. The disregard of these consequences which is implicit in the use of a short-period demand curve to determine long-period equilibrium is a major element in P. W. S. Andrews' attack on current theories of the firm.* Similarly, although complete independence implies complete absence of control, there can be no posidon of authority which confers absolute powers of control. Even where there is no possibility of escape from a superior's jurisdiction, the exerdse of authority is restricted by the alternadves to obedience open to subordinates, which can be subde and devious, as every soldier knows, and also by the risk of provoking acdons which will seriously limit the superior's nominal authority. (One remembers the descripdon of the Czarist system of government in Russia as 'absoludsm tempered by assassinadon'.) The concept of 'countervailing power' is of some relevance to organisadonal as well as economic reladonships. Thus it is not surprising that, at a dme when there has been a seller's ' Andrews, P. W. S., On Gompetition in Economic Theory, London: Macmillan, 1964. 354 THE JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT STUDIES OCTOBER market for managers as well as for workers, and when therefore the available sanctions have lost much of their force, there has been more emphasis on the nodon that authority is something accepted from below, rather than enforced from above. Superiors are now exhorted to lead rather than to drive. But before accepting that the efficacy of sancdons is limited solely by such factors, it should be nodced that among military commanders, who have the strongest sanctions at their disposal, qualides of leadership have always been very highly valued. It must be conduded that authority, though it may be of considerable, indeed indispensable, value in securing the acceptance of organizadonal goals, cannot guarantee their acceptance. If conformity to organizational objectives cannot always be enforced, neither can it always be bought. The flaw in the economists' approach is the assumpdon that sadsfacdons are obtained always with the proceeds of work, never in the process of work. That this assumpdon quite often appears to be jusdfied, at least on the shop floor, cannot be denied: but one is nowadays likely to hear it argued quite strongly that this is a self-jusdfying assumption rather than a basic truth. If workers are given no opportunity of gaining any sadsfacdon from their work, they will inevitably appear to be interested only in their pay. Whatever may be the truth on the shop floor, it is surely the case that managers seek to satisfy some of their most important wants through the work that they do, and not only by spending the cash which they earn. The sadsfacdon of these wants, espedally for higher management, is likely to impinge direcdy upon the objecdves of the organizadon. In these circumstances, organizadonal goals, far from being accepted in return for proffered inducements, must act as significant inducements themselves. Instead of hiring managers to carry out a predetermined policy, a firm may have to formulate a policy which will succeed in attracting managers. Thus the distincdon between 'inducement objecdves' — what do we need to do to stay in business — and 'direcdon objecdves' — what is our business — breaks down. Inducement objecdves become direction objectives. The Formulation of Organiv^ational Goals From the growing recognidon of the defidencies of both the 'incendve' and the 'authority' theories there have emerged two modern explanadons of the relationship between individual and organizadonal goals. The earlier, and in our terms the less revolutionary, is assodated particularly with the name of Douglas McGregor,* who, denouncing authoritarianism both for its ineffidency and for its failure to meet some of the basic needs of managers^ argues that conformity between individual and organizational goals can best •McGregor, Douglas, The Human Side of Enterprise, New York: McGraw-Hill, i960, esp. Chaps. 2-4, 9. 1968 THE DECISION-MAKER IN THE ORGANIZATION 355 be achieved if the latter are the product of a consensus: if a manager helps to set organizadonal goals, he will accept them as his own during the working day. As a prescripdon for enlightened management, McGregor's advice has much to recommend it. But it does not solve our problem. As President Johnson would no doubt be the first to admit, it is not easy to maintain a working consensus. Genuine conflicts of interest do exist, and some of these conflicts must somehow be accommodated within any large organization. American polides are normally discussed, and practised, far more openly in terms of interest groups than British polides; political alliances rely on bargaining as well as limited consensus. In both countries this bargaining is supported by the use of phrases which can be — and are intended to be — interpreted quite differendy by different groups. This has been a notable feature of Harold Wilson's technique. In some circumstances, free and open discussion may produce a true 'meedng of the minds'; in others, poor communications and misunderstandings may be among the most effecdve forces holding an organizadon together. It is in this spirit of polidcal realism that Cyert and March discuss the formation of organisadonal goals.® Arguing that a consensus is in any large organizadon difficult to construct, that where there are major conflicts of interest (which is not unusual) it is impossible to achieve, and furthermore that organizadons can funcdon quite successfully without it, they suggest that organizadonal goals are best viewed expliddy as the outcome of a bargaining process, which is likely to leave many issues unresolved. These unresolved issues are submerged by four factors: first, the inability of the pardes concerned to appreciate them all (limited radonality); second, the infrequent need to face more than one or two of them at a time (sequendal attendon to goals); third, the use of phrases, such as 'an aggressive markedng policy' or 'purposive and pragmadc government', which provides no unambiguous standard of measurement (non-operadonal objecdves); and fourth, the possibility, as long as the organizadon is not fully stretched to meet its external commitments, of simultaneously sadsfying potendally conflicdng minimum demands (organizational slack). These issues are submerged, not settled, and when the relevant factor ceases to be effective — when, for example, a fresh problem forces a hitherto-avoided confrontadon, when a non-operadonal objecdve becomes operational, when organizadonal slack dwindles in hard dmes — they break surface again, and can cause a great deal of trouble. Its power to explain the emergence of formerly-suppressed conflicts within organizadons is just one of the many attractions of the Cyert and March = Cyert, R. M. and March, J. G., A Bthavioral Theory of the Firm, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1963, Chap. 5. 356 THE JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT STUDIES OCTOBER approach. They have opened the way to a treatment of the firm as both an economic and a political unit. (Incidentally, it is notable how much progress has been made in integrating political and economic issues in analysing developments in Communist countries.) But this particular merit is largely neglected in their own work. Though their theory is far removed from the old assumption that organizational goals are either sold to or imposed upon decision-makers within organizations, though on the contrary they insist that specific attention be given to the process of goal-formation, yet they still adhere to the even more fundamental assumption that a knowledge of organizational goals — an understanding which they have notably advanced — is sufficient to explain decisions within organizations. This assumption is surely wrong. The Inadequacy of Organisational Goals as Determinants of Behaviour The decision to join an organization as a manager implies the perceived compatibility — or potential compatibility, if there is a chance of modifying the latter — of personal and organizational objectives. It does not imply the acceptance of organizationally-determined criteria for decision-making. Even if a manager should identify himself completely with the goals of his firm, it is usually not rational for him to pursue them without personal incentives. For a corporate goal is a collective good to all those who desire it; and unless the contribution required is very small, it is not usually rational to contribute to the supply of a collective good. As one manager among many, one's own contribution can make little difference either way; the result depends on other people's efforts. What is generally desired, and must be made freely available, if available at all, will not be individually sought.^ The theory of collective goods demonstrates the fallacy in the argument that members of an organization should share a common purpose. It is not just that a common purpose is unnecessary as a rational incentive; it is actually worthless. Joint purposes, not common purposes, are the efficient engines of action.'' A collective good may provide a rational incentive if it is common to only a small group; for then the contribution of a single person may significantly affect the supply of the good, and his share of the benefit may outweigh the cost of his contribution. Thus corporate objectives may motivate top management; and lower levels of management may be activated by sub-group objectives. But often the strongest incentive will be to pursue individual objectives. Thus the natural tendency of the rational manager is to pursue first his own objectives, second, his sub-group's objectives, and the objectives 'Olson, M., The hogic of Collective A.ction, Cambridge, Mass.; Harvard University Press, 1965. ' This point has been emphasized by my former colleague, Mr. D. K. Clarke, now Principal of Swinton Conservative College. 1968 THE DECISION-MAKER IN THE ORGANIZATION 357 of larger groups feebly if at all. How closely his decisions conform to the overall goals of the organization depends on the degree of discretion he is allowed and on the organization's control system — interpreting the latter, as will be explained shortly, in the widest sense. Decisions cannot be delegated without giving the decision-maker the power to make organizationally-perverse choices. Yet delegation can scarcely be avoided. In an organization of any size, no one man can have either the time or the information to make all the decisions; moreover the attempt to keep all decisions in his hands is likely seriously to reduce the quality of his subordinates, and thus to impair the information used in making his decisions, of which they must remain a major source. How closely the actions of a decision-maker within an organization conform to the interests of that organization depends on the effective jointness of his own and the organization's objectives. The link between the two is the management control system. Management Control Systems The technical problems of constructing a system which will measure a manager's performance in terms of the desired objectives are well understood, though, as the literature of the subject clearly demonstrates, they are far from completely solved. What are the elements of good performance ? How can the non-measurable elements be dealt with, in order to avoid a concentration of the manager's attention upon the measurable ? How can one avoid a situation in which a manager can improve his own recorded performance at the expense of the organization as a whole ? Such questions are the staple of discussion, and there is plenty of guidance available. The companion problems, of devising an incentive system that will effectively motivate the improvement of the performance so monitored, has also attracted a good deal of attention, but it has not been so well resolved. There is disagreement over the relative effectiveness of different incentives; and this disagreement is unnecessarily exacerbated by a failure to realize that different managers may seek different kinds of satisfaction, and also by a failure to realise that a manager, like anyone else, is entitled to forgo a proffered incentive if he chooses; he cannot be compelled to conform to the preferences of the control system. The trouble is that discussions of the incentive elements in management control systems have not yet completed their escape from the outworn assumptions that confornaity between organizational and individual goals can be secured by a combination of sanctions and financial reward. The consequences of escape are far-reaching. To a manager who is seeking satisfactions from the content of his work, the management control system, instead of providing a mechanism for directing his activities, becomes 558 THE JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT STUDIES OCTOBER itself part of the inducement. The whole organization must be regarded as a control system. This view is supported by R. I. Tricker,^ who writes (privately) that 'we must look on business control systems within the context of a business total system, rather than as a controlling mechanism added on top. In other words, we must study man/machine systems instead of accounting paper work systems.' The kind of management control system used in an organization may be a vital influence on an individual's decision whether to join. The absence of tight control is frequently argued as essential to the recruitment of good university staff and of good industrial scientists. But if the freedom to make decisions with a substantial element of discretion is used as an inducement to join, then the organization is offering, not merely the right to join in the formulation of organizational goals, but the right to pursue, within some limits, individual objectives when making decisions within the company. In these drcumstances it is not only the distinction between inducement and direction objectives that breaks down, but also the distinction between organizational and individual objectives. Such freedom of action is particularly likely to be offered to managers near the top of an organization, who may indeed be allowed to pursue their own objectives and also to attempt to impose these objectives on their subordinates as organization objectives. If this is so, then, as has been argued by a senior officer in a large consulting organization, • one ought to talk of the objectives of a group of senior executives, rather than of the objectives of a firm. Many of that company's corporate planning assignments reflect this attitude. The consultants set out to elicit the objectives of the major decision-makers — objectives which are by no means always apparent to their colleagues — and then attempt to devise a policy which takes explidt account of them. This approach is in the spirit of McGregor's recommendations; it has also been advocated in an article by Guth and Tagiuri.^" So far, we have discussed managerial discretion as a deliberate grant in order to recruit and stimulate good managers. But some discretion is inevitable in the absence of perfect knowledge. This discretion may arise from three causes. First, the uncertainty surrounding most dedsions often makes it difficult to assess the correctness of the choice made. Second, it is almost impossible to review a dedsion by a specialist — and even more impossible to review a dedsion by a group of spedalists — without having the dedsion made afresh by another spedalist (or group of specialists); and this, besides costing time and money, is Ukely to lose one the services of the spedalists ' Barclays Bank Professor of Management Information Systems at the University of Warwick. » Magee, J. F., of Arthur D. Little, Inc. " Guth, W. D. and Tagiuri, R., 'Personal Values and Corporate Strategies', Harvard Business Reviea, September-October 1965. THE DECISION-MAKER IN THE ORGANIZATION 359 SO treated. Authority, in the sense of having one's word accepted, can flow upwards as well as down. Third, subordinates have a good deal of control over the information which their superiors use, induding the information on which they are judged. As was stated earlier, the technical problems of constructing a system which will measure a manager's performance in terms of the desired objectives are well understood; but the problems are not merely technical. It is far too readily assumed (as it is for instance in David Solomons' Divisional Performance: Measurement and Controiy^ that both the recorded performance and the standards against which it is judged represent objective truth. But a budget is a political as well as an economic document, as Cyert and March have pointed out; many budget items represent commitments rather than constraints. In addition, budgetary standards are liable to suffer from the attempt to achieve two conflicting aims. One aim is to provide a guide to action by the manager himself, by drawing attention to problems through the recording of variances; the other is to assist in evaluating the manager, by recording his shortcomings. On the first criterion, an unfavourable variance indicates the need for action; on the second criterion it indicates the failure of previous action. It is not surprising, therefore, that, as W. F. Pounds of the Sloan School at M.I.T. has found, there is liable to be an emphasis on the setting of budgetary standards which will indicate neither problems nor failures. ^^ Sometimes this emphasis is supported by the superior of the manager being evaluated (probably because he does not enjoy giving a reprimand^^ and also because any failure by his subordinates may harm his own standing) and may become an open conspiracy throughout the company. When this happens, the control system is occupying a good deal of time, and some ingenuity, in making management less effective by concealing problems which deserve attention. Even if such inflation of budgets is not a general implicit policy, the individual may still have some control over the standards by which he is judged. Indeed it is an artide of the modern budgetary controller's faith that a budget must be accepted by the manager to whom it is to be applied. The budget then is the result of bargaining; it is not analytically determined. An experienced consultant, writing about the control of his own work, says, 'A technique which I enjoy . . . is to have a sufficiently large cushion in each ^1 Solomons, D., Divisional Performance. Measurement and Control, New York: Financial Executives Research Foundation, 196J. " Pounds, W. F., 'The Process of Problem Finding' (M.I.T. Sloan School of Management Working Paper, 165-65, 1965), pp. 16-18. " For evidence of this attitude, see Rowe, K. H., 'An Appraisal of Appraisals,' fournal of Management Sjudies, Vol. I, No. i, March 1964, pp. 1-25. 360 THE JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT STUDIES OCTOBER case that it isn't necessary to keep a close and continual watch on actual expenditure'.^* If budgets do not embody political commitments, guaranteeing a certain expenditure, then they are liable to be fudged, with or without general approval. If neither of these measures are adequate to frustrate the control system, there are often means available to influence the recorded figures. If there is a danger of underspending, it is not usually difficult to spend a little more (and there are surely not many managers who have never been asked to suggest some supplementary expenditure in order to use up a budgeted allowance); if there is a danger of overspending, there are a number of methods for hiding or misreporting expenditures. What can happen even in a technically efficient management control system is illustrated hy the following example. ^^ 'Asked what data he used for making decisions about the running of his department [a production manager] produced a sheaf of his own running notes on relative plant performances under various conditions. Questioned why the control accounting data did not reflect similar patterns, he explained that the control data was originated hy him for the accountants and he told them what he thought they wanted to know. He had found that there was much criticism at the monthly meetings if his weekly performances fluctuated a lot. In fact, he explained, because of a multitude of variables, the results did really fluctuate. What he did in reporting was to average the figures to show reasonable consistency, keeping the excesses on good weeks to ease the results in bad weeks. As he put it, "I keep a bit of production up me sleeve to save my neck'." Why should we assume that managers are less skilful than operatives in controlling the reported results of their work? Neither the target nor the reported figures of an accountant's control system necessarily represent reality; on the contrary, all formal control systems nuy he expected to generate misinformation. The Extent of Managerial Discretion Thus a manager often has a freedom of choice which is not merely nominal. Organizational objectives specify the limits (though as we have seen, not always precisely) but they do not prescribe the choice. The extent of this remaining freedom is obscured by the ambiguity of the word 'judgement'. Managerial judgement does not consist solely in making a good estimate of the situation and evaluating various courses of action; it also consists in deciding how to choose within the limits which organizational criteria prescrihe. That such an effective freedom exists is adnutted hy any salary 1* Private communication. " Tricker, R. I., The Accountant in Management, London: Batsford, 1967, p. 83. THE DECISION-MAKER IN THE ORGANIZATION 361 scheme which rewards responsibiHty; it is made expUcit in Eliot Jaques' Equitable Payment,^^ which advocates a salary structure related to the 'timespan of discretion'. The existence of managerial discretion poses a problem for modern, as well as for old-fashioned, theories of decision-making. Contrary to the claims of its exponents, satisfying theory does not provide a unique criterion for decision. The organization does not require above-satisfactory performance;, but it does not necessarily penalize it. The requirements of satisficing prescribe a feasible set of solutions — the set may of course be empty — but it offers no rule for making a choice within that set. The concept of managerial slack may be seen as an attempt to preserve organizational objectives as adequate predictors of behaviour by postulating that no attempt will be made to improve upon satisfactory performance." But the attempt cannot succeed. The preference for slack over improved performance must be an individual, not an organizational decision; it cannot be deduced from organizational goals alone. This is not the only objection. Even if satisfactory performance, by the standards of the organization, were to be accepted as a criterion, and not simply as a constraint, individual preferences still could not, in general, be excluded. There is no general reason why the subset of minimum solutions within the feasible set should contain only a single element; satisfactory performance can often be achieved in several ways. It is up to the decisionmaker to choose. Indeed, one of McGregor's recommendations is that managers should allow subordinates to follow their own preferences in choosing between several ways of achieving a desired result." This difficulty cannot be evaded by postulating a process of sequential search. Such a process leads to the acceptance of the first satisfactory solution to be discovered, but it does not explain which of the various satisfactory solutions will be discovered first. What appears to be the most obvious solution to one man, with a particular pattern of experience, does not necessarily appear to be the most obvious to another, whose experience has been different. Company histories may tend to over-emphasize the importance of individuals, but to deny them any importance would be absurd. The reason why Cyert and March's book ignores this problem is probably that their detailed model is designed to explain repetitive decisions within a stable organization. These are the conditions which produce 'organizational learning' and standard solutions.is But if the situations calling for action repeat themselves only infrequently, and there is a good deal of movement " " " " Jaques, E., Equitable Payment, London: Heinemann, 1961.' Cyert and March, op. cit., pp. 36-8. McGregor, op. cit.. Chap. 9. Cyert and March, op. cit., pp. ioo-i. 362 THE JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT STUDIES OCTOBER of managers into the organization, hringing diverse kinds of outside experience with them, then organizational learning will be rudimentary at best, and there will be no standard solutions. Cyert and March's concentration on short-period, repetitive problems also leads to the neglect of another issue. Why should the first satisfactory solution produced by a sequential search procedure necessarily be a minimum solution? If" the searcher has a repertoire of standard solutions, the assumption may he reasonable; but for long-term, non-repetitive problems such repertoires, and such minimum solutions, are a good deal less likely. The major innovations of economic development are indeed striking instances of solutions which rise well heyond the requirements of satisficing. In general, the Carnegie school provides a better analysis of short-term than of long-term decision-making. But even in short-period situations it is impossible to eliminate the individual. It is surely illegitimate to assume that managers who are capable of performance above the level required by their organization should always choose to employ those abilities in ways that have no effect on that organisation. The abandonment of such an assumption does not require the abandonment of the satisficing approach; it simply means acknowledging that the individual's standard of satisfaction may well be above the level prescribed by organizational objectives. W. F. Pounds has observed that plans are organisationally defined limits of managerial independence; as long as a manager's performance does not fall short of the plan, he is free to choose his own problems, free of organizational control (though not of course free of many influences).^" Some organizations, recognizing that some freedom of managerial action cannot be prevented, have deliherately chosen to increase that freedom in the hope of stimulating individuals to set themselves higher standards than the organization could ever hope to impose. A large consulting company, for instance, uses the ahsence of an elaborate formal control system as an essential element in its overall managerial system. In such an organization decisions cannot be explained without reference to individual objectives; for example in the consulting company the kind of new business brought in is substantially dependent on the initiative of individual consultants. Even if there is no deliberate attempt to make productive use of the resources which are not needed to meet minimum objectives — even if 'slack payments' are designed to meet purely personal objectives — these objectives may still be relevant to the history of the firm. For example, if an unnecessarily large research department is established solely to satisfy the Research Director's empire-building ambitions, without any reference to the needs of the firm, that research department may nevertheless produce ideas which have a major impact on the company. As Cyert and March "• Pounds, op. cit., p. 16. 1968 THE DECISION-MAKER IN THE ORGANIZATION 363 themselves observe, 'Slack provides a source of funds for innovations that would not be approved in the face of scardty but that have strong subunit support.'21 But the implications of managerial discretion for their own theory do not seem to be recognized. The Influence of the Organi^^ation on Individual Objectives It is necessary, therefore, to consider individual objectives in explaining dedsions, as well as in explaining the formation of organizational objectives. Individual objectives, however, are not completdy independent objectives. A potentially useful way of analysing individual objectives is provided by the dassification of problem-finding models suggested by Pounds. Such an analysis of a particular manager's objectives in terms of his own experience (historical models), the experience of others (extra-organizational models), and the demands of the organization (planning models) appears to offer a way of focusing upon the individual dedsion-maker without treating him in isolation. When considering the individual, it might be particularly convenient to distinguish between extra-organizational models which are entirely outside the organization in which the individual works and extraorganizational modds — perhaps better called extra-personal models — which are yet within that organization. As an example of the use of this kind of analysis, it is possible to suggest some influences which would tend to keep the standards in the individual manager's problem-generating models down to the levels prescribed by the organization — so that satisficing for the individual would mean the same as satisfidng for the organization, as the present Carnegie theory assumes. The organization's apparent, if implidt, models of managerial behaviour are influences of obvious importance. This indeed is the burden of McGregor's argument: if a firm dearly expects managers to do no more than the firm's formal control system can compel them to do, then those managers are likely to accept the consequences of Theory X as their own model too, to use managerial slack to fulfil personal objectives which are irrelevant to the performance of the company. If on the other hand, says McGregor, the firm's model is Theory Y, then there is a very good chance that the firm's managers will use Theory Y also — and Theory Y implies that individual targets will be set higher than the firm's targets, and that managers will seek to satisfy their personal objectives in ways which assist the company. The models of fellow-managers are also important. The phenomenon of group control is not confined to the shop floor, and managers can learn from their peers not to spoil the job. (The managers studied by Pounds, who were disturbed by the possible effects of this year's good performance on ^' Cyert and March, op. cit., p. 279. 24 364 THE JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT STUDIES OCTOBER next year's targets, obviously had some such model of behaviour.)^^ The existence of many submerged issues may also be a restraining factor. Aboveminimum solutions are liable to have a wider impact within the firm, and thus risk raising some of these issues. Past experience of the consequences of raising them, and a knowledge of the conflicting objectives that exist, are likely to be important influences on the choice made by a manager who can opt for an adequate or for a better solution. In the last resort, the organization which wishes to be highly successful cannot rely on organizational objectives to secure that success. At least it cannot rely on organizational objectives which are subject to organizational control. The routine and the regular can be thus dealt with. Procedures for initiating action can be established and solutions can be closely linked to problems. Armies have shown that men can be trained to react instinctively to foreseen situations. But initiative cannot be commanded. Operational models cannot be provided in advance for unforeseen problems. There is logically no way in which one can tell that a problem should have been recognized until it has actually been recognized. If it was not recognized in time, when it is recognized it is too late to demand earlier recognition. Thus for long-run problems, the establishment of operational objectives is of limited use. One must rely on the individual; and one may have to rely on a fairly low-ranking individual to give timely warning that action is needed. This is not to say that the organization has no control over the situation. It has; but its control lies in its ability to influence the standards which the individual sets for himself. Such influence results from the impression which it gives of its conception of good management (and detailed performance targets may not give the impression they are intended to give) and from the scope which it offers for the individual manager to achieve his personal objectives in (and not merely by means of) his performance as a manager. Pounds, op. cit. p.