'THE VOYAGE OF ERIK THE VIKING'

advertisement

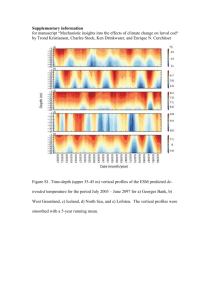

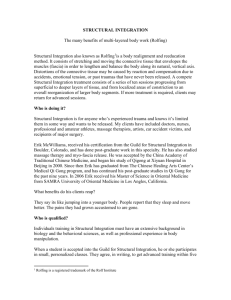

REPORT TO THE WINSTON CHURCHILL MEMORIAL TRUST ‘THE VOYAGE OF ERIK THE VIKING’ ALEXANDRA FITZSIMMONS, FELLOW OF 2007 Contents Introduction Life in Turf houses: Viking days in Iceland and Greenland All aboard! An Icelander explains that it’s easy to sail to America in a Viking ship Colonising peoples: an argument over sustainability Religious leanings: Erik’s dispute with his wife and its result in Viking heritage Conclusion: writer’s fever and the art of living it twice. Note on spelling: Icelandic uses certain letters which are unfamiliar in English and for ease of reading I have used English spellings throughout. I have made exceptions for a few Icelandic terms, which are italicised – in these cases the Icelandic letter ð is pronounced th, as in this. Acknowledgements: thanks to the WCMT and the Eranda Foundation for generous funding; Royal Arctic Line for hospitality at sea; all those I met during my Fellowship including particularly for this report Bjarni F Einarsson at Hólmur, Gunnar Marel Eggertsson in Keflavík, Jón Jónsson and Sigurður Atlason in Holmavík, staff at the Reykjavík 871± 2 exhibition, the family at Drangar, Ingibjörg Gisladottir at Qassiarsuk, Finn Lynge at Narsaq. Finally, a particularly key text has been W.Fitzhugh and E.Ward (eds.) 2000, Vikings – The North Atlantic Saga. Introduction A foggy, windy day off the coast of north-west Iceland. A small rubber boat is lowered slowly from the back of a ferry and two figures slip down into it, one confidently, one more cautiously. The engine sputters and the dinghy shoots off across the bay, the second passenger clinging tightly to the side. She shivers, but looks ahead. Through the mist, the shoreline is becoming visible, muted greens and browns. There’s a wooden landing stage, a slippery slope of aged planks vanishing into the dark water. Three splashes of colour behind it morph into raincoated human figures. The boat chugs to a halt: hands stretch out; the passenger grasps them and is helped ashore, careful of her footing, slowly making it to solid earth. Words are exchanged, in Icelandic. The captain revs up the engine again: the boat moves off. Those left behind watch as the fog swallows it up. The newcomer is the first to turn around. What next? Having reached this remote cove, what will she say to these people? She looks at their faces, weatherbeaten and cheery, wonders. Then a man walks by in bright orange raingear and the men’s faces break into smiles. “If you wait fifteen minutes and then follow him,” grins one, “ you will find a naked Viking in his bathtub.” *** I am following the journey of Erik the Red, the Viking explorer who – according to the Norse Sagas – was the first European in Greenland, a thousand years ago. Erik was – it is said – born in Norway, in Jaeren, the region around modern Stavanger. One day, his father was exiled for fighting, and he and Erik set out for Iceland. There was little choice of settling-place, so they colonised a remote bay in Iceland’s north-west fjords – this bay I have just discovered, today inhabited by raincoated Icelanders. But this is only the beginning of my, and of Erik’s journeys. I have followed him from Norway to Iceland, and now I plan to follow him further, going south again to the region where he lived as a married man. With his wife Thjodhild, Erik farmed here for a while, until he had a fight with a neighbour and had to move west. It did no good: my next visit is set for the site of the parliament where, after further disagreements and skirmishes, Erik was eventually thrown out of Iceland. He then took to his boats and sailed off west, into the open ocean. Map sketching my route, approximately in Erik’s tracks. Erik’s own route is not precisely recorded, but areas associated with him are Jaeren (around Stavanger), NW Iceland, and other regions in its west, and the Nuuk and Qaqortoq regions in Greenland. Map: Google Maps. I plan, unlike Erik, then to return to Iceland’s capital, Reykjavík, where are to be found some of the manuscripts which hold Erik’s story. After looking at these I will find a boat to take me further in his tracks, crossing the North Atlantic and entering the Davis Strait, exploring up and down the south-west coast of Greenland. *** I wait a little longer before visiting the bathtub, and find it empty – but genuinely a natural bath, warm water flowing into a hollow in the rock beneath the mist. My guides swear to me that it has been in use for hundreds of years, probably since Erik the Red himself sat in it, dreaming of voyages across the world. I warm my hands in the water before turning back, continuing my own quest to follow him across the northern oceans. *** The aims of my 2007 Churchill Fellowship were various. Primarily, I was following the route of a Viking explorer, investigating past and present so as to write the story of not one but two adventures on my return. I hoped this way to bring life to the story of Erik’s journey, which as told in the Sagas is minimal on detail of scenery and day-to-day life. Original readers (or tellers) of the Sagas would have understood these details automatically, but for a modern audience it is more difficult. But I did not only want to bring life to the Sagas. All stories are ‘tools to think with,’ providing a way to re-understand the world. Erik’s story can help bring into focus questions about colonising new lands – both about exploration and about sustainability – and about religion. Erik ultimately colonised Greenland, setting up a European farming lifestyle in the far North: how hard was that, and how were these Northern lands affected by an influx of Viking farmers? Erik was a stolid worshipper of the Norse gods at a time when Christianity was being introduced across Iceland and Greenland: why couldn’t those of the two faiths live together? And a final question: how important is Erik to Icelanders and Greenlanders today, and why? Any discussion of Erik the Red must be prefixed by a quibble: the man may not have existed. The sagas that describe him are stories of lives lived, battles fought, bodies raised from the dead, shipwrecks and one-legged monsters. Parts are clearly fiction, exaggeration, or confusion. But – traces of houses have been found where houses were described. Settlements are where, and when, settlements should be. Definitely, someone made each of these journeys – from Norway to Iceland and from Iceland to Greenland – at about the time Erik the Red is said to have lived. Quite possibly Erik is a historical figure. Even if not, though: even if he is the purest of fiction, his story is so good – and has been told so often and for so many reasons – that it is worth a visit for its own sake. The final product of my Fellowship will be a travel book in which my and Erik’s story, and these and other debates, are mingled. At time of writing, the book is in draft form. The Report that follows is a taster: there is something about Viking daily life in Iceland and Greenland, something about making a voyage in a Viking boat, something about colonising new lands, something about religion and Viking heritage. To conclude, there is a section about writing: the strangeness of travel writing for me lies in the way it makes one live twice, once experiencing and once recording every significant event. Drangar, in north-west Iceland: the bay where Erik and his father are said to have settled. Life in Turf Houses: Viking days in Iceland Wind blows, hard, across the valley’s entrance, and the mountains rising around it are tall, wild, snowy. Way below them, bumping and lurching across the grass, is a rugged Landrover. It pulls to a halt. Fifty yards away, a patch of turf has been cut away, and a hole dug deep in the soil. A man and a woman step out of the vehicle, banging the doors behind them. He strides confidently: she follows close behind. When they reach the edge of the pit he gestures across it, pointing where the earth is slightly lighter, patterned in patches with blotchy swirls. *** Bjarni F Einarsson was showing me the ruins of turf walls, to the uninitiated no more than a pattern in the earth. We were at Hólmur, his excavation site near Höfn in southern Iceland. Turf is the perfect building medium for Iceland. Very insulating and widely available, it was the material of choice for Icelandic houses through most of Iceland’s history: only in the nineteenth century did Icelanders began importing wood from Norway for building. Erik’s house would certainly have been built from turf. Left to right: turf house at Eiríksstadir, nr. Budardalur; interior turf wall at the Sorcerer’s Cottage in Bjarnarfjordur, in the Westfjords; remains of a turf wall at Hólmur. The skills for building with turf survive – just. In Iceland there are reconstructed turf houses to visit: in one I sat comfortably on sheepskin rugs, trying out a sword for size, while in another I opened the door only to reel away as the scent of sheep overpowered me. An impressive amount is known about what went on inside these houses, gleaned from scraps and objects found on the floors. Typically, the building itself was long and narrow, with the back wall slightly curved outwards. The main door was towards one end, and beds (or benches) stretched along each long side. It’s thought that the family slept against one wall, and slaves against the opposite. Along the centre of the room was a stone hearth. Often these houses would have extensions, added over time, and outhouses with different functions. Fish-oil lamps and firelight lit the dark interior, where women spent many days spinning and weaving, making cloth from the sheep’s wool. It was this that kept everyone warm. The cloth was also used for making the sails of ships, and was so valuable it was used as currency. Inside the house too, food was prepared and eaten. In Iceland, fish, lamb and dairy products were the mainstay of settlers’ diets: grain cannot really be grown so there was little bread. What there was, was flat-bread, baked on the hearth. Birds and eggs were important too – puffins caught easily off the cliffs. Two Icelandic foodstuffs are especially worth mentioning: skyr and harðfiskur. The first is a cross between yoghourt and cream cheese: to make it, you make yoghourt from milk and then turn it into cheese by adding rennet. The result is white, thick and creamy, with flavours of both cheese and yoghourt. Today’s skyr comes in different flavours, blueberry, strawberry or vanilla, in little pots with spoons in the lids. In Erik’s day, skyr would have been stored in a barrel and served with honey or maybe even seaweed. The second, harðfiskur, is dried fish. In the supermarkets today, it comes packaged up like crisps: you can buy a wilder sort down by the harbour. A cynic would say it tasted like old fish, with the texture of disintegrating cardboard. With butter however, and eaten in the open air, the flavour has a little more richness... a little less fishiness... gourmets will declare one fish, catfish, especially delectable dried. A good thing I came to like it because amidst the many uncertainties about Erik, one thing is sure: anyone with any sense making a voyage from Iceland would have taken a lightweight, protein-rich and, er, yummy food like dried fish. Harðfiskur and skyr for sale in Iceland. All aboard! An Icelander explains that it’s easy to sail to America in a Viking ship A beach. A field ringed round with fencing, and in its centre a boat. A lonely figure approaches, feet crunching first on the lava pebbles that line the shore, then softly treading across the grass. She pauses, looks back at the ocean. Then she turns to the ship in its field and it is as if she has frozen time. Entirely still, she takes in its high prow, the long strips of oak that seem to reach from end to end, the tall mast reaching upwards to where clouds sit, covering the sky. Then a battered jeep rattles into the field, and the trance is broken. *** Gunnar Marel Eggertsson is the driver of the jeep: he is also a man who has sailed to America in a Viking boat. Actually, this is the least of his achievements: he has sailed as far as Rio de Janeiro, further than the Vikings are even rumoured to have made it. Gunnar Marel Eggertsson’s reconstruction of a Viking longship: she has sailed to America and back. Gunnar Marel considers it his mission in life to prove that the Viking voyages of discovery – Erik’s amongst them – were really possible. Íslendingur is the latest of his boats: she was built for the Millennium, arriving in New York a thousand years after the first Viking boats, one captained by Erik’s son Leif, are said to have made the voyage to (more northerly) America. It is this sort of boat, explains Gunnar Marel, that made the voyages of discovery possible. She is stable and speedy – and capacious. It is thanks to this sort of boat that Iceland’s history began – thousands of emigrants from Scandinavian lands moving west to colonise the almost empty island, about twelve hundred years ago. All the wood in Íslendingur came from Norwegian forests, every piece chosen individually, each tree selected for the positioning of the knots in the wood. Iceland does not have the forests for boat-building, nor is she likely to have had them in Erik’s day. So far, the construction process was similar to that which would have been used a thousand years ago. For the actual building, Gunnar Marel admits to using electric tools, but this added power to the process, rather than changing it fundamentally. Íslendingur took a year to construct. I ask how long it took to sail to Greenland, and on to America. I don’t know what answer I expect – a month? Three months? I am way over. It takes about a week to get to Greenland in a Viking boat, and a week more to get to New York. Gunnar Marel assures me that weather is only a little bit of a problem: you try to avoid the worst, like storms with twenty-metre waves. To put this in context, Íslendingur’s mast is about twenty metres high. Ice round the coast of Greenland can delay a journey even for a modern hulk. In winter the more northerly waters are frozen. In spring, drift ice and pieces from glaciers block the fjords to the south, sometimes so closely packed and so hard that a boat cannot move between the bergs. Erik would have faced more challenges than the need to build a boat and the prospect of bad weather and ice. In his day the compass had not been invented, let alone GPS. Navigation seems to have been by landmark: ancient sources describe – for instance – ships sailing past Iceland so as only to see the birds off the coast. But Gunnar Marel has an answer for this too. “It is just island hopping,” he explains. On a clear day, Iceland is visible from the Faroe Islands; Greenland is visible from the Westfjords, the part of Iceland where Erik and his father settled. Baffin Island, at the north of Canada, is visible from the west coast of Greenland. So it’s quite possible that Erik knew where he was going, when he set out to discover new land in his period of exile. His boat, skilfully constructed from specially selected woods, did not head entirely into the unknown. Colonising peoples: an argument over sustainability and normality The sealskins are piled up around the outside of the room. Some retain their natural colours, soft browns and speckled. Others have been dyed, and gaudy colours glow. The guide lays her hand on one, stroking as she talks, explaining the different classes of fur, the different ways the skins can become damaged in preparation. And one other thing: that the whole animal was once eaten, but that now chicken wings, imported from Denmark, are cheaper than local seal meat. “It is a problem,” she says. *** Seals have been at the heart of Greenland’s economy for all its colonised history. To the traditional Thule Inuit1, who arrived in Greenland around the same time as Erik’s colonising group2, seals were vital. The skins were stretched over wood to make boats, became the walls of tents, were sewn together to make clothing worn fur-side-in in winter and fur-side-out in summer. The stomach was emptied, inflated and dried, used as a float, or used as a bag to contain preserved food. The meat was eaten, every part, fresh and dried. The blubber was used as fat and as candle-fat. Without seal, Thule lifestyles would have been very different – perhaps impossible. Left: fjord in South Greenland. Right, traditional skin tent in Greenland’s National Museum, Nuuk. 1 2 Formerly known to Europeans as Eskimos Well, within a few hundred years. Such Norse3 buildings as have been excavated have yielded high numbers of seal-bones, suggesting that seal was an important element of diets. But they were not everything. The Norse were not primarily hunters but sheep-farmers – and questions have been asked about how their farming activities changed Greenland’s landscape. The Norse settlement certainly affected the flora: even today, certain plants are found around Norse ruins that are found nowhere else in Greenland. Questions have also been asked about how much deforestation took place to create farmland. Trees do not easily grow back this far north – so was sheep-farming sustainable here, or did it just cause the land to erode faster once these largest plants had gone? Another debate in the scholarship is the degree to which the Norse were dependent on Europe. Certainly, there were many European habits that did not change – farming and hunting styles amongst them. For example, only certain sorts of seals’ bones have been found at Norse sites, suggesting that the inhabitants of the colonies Erik founded never learnt to hunt the seals with harpoons as Thule Inuit did but attacked those they found on land, clubbing them or netting them. The Norse inability to use a harpoon has even been cited as a reason for the eventual disappearance of the Norse colonies in Greenland. These vanished in the fifteenth century while Thule Inuit inhabitants survived: one difference between the two populations was hunting style. Perhaps the Norse lack of skill cut that group off from a key food supply, contributing to their demise.4 Now, Greenland is a part of Denmark. Previously it was a colony, and populations of Danish and Thule origin have been sharing the Greenlandic landmass for centuries. To skip over hundreds of years of history, nowadays most food in Greenland is imported from Denmark. This is one effect of the movement of Greenland’s population into cities from isolated settlements, begun in the 1950s as part of a – now controversial – effort to give Greenlanders access to facilities that were standard in Europe. While the benefits of 3 In this context, this is a more appropriate term than Viking for settlers of Scandinavian origin. 4 See T.McGovern, The Demise of the Norse, in W.Fitzhugh and E.Ward (eds.) 2000, Vikings – The North Atlantic Saga hospitals and schools cannot be denied, the changes caused turbulence amongst the population, social units thrown into confusion. Not all that was Greenlandic disappeared: the language was campaigned for and saved. But many traditional Greenlandic practices vanished, fast. To return to food, Greenlanders still eat seal – but less and less. They still use skins, but less and less. Chicken wings, and man-made fibres, are cheaper. European diets are becoming standard. One first reaction is: hooray! The seals are safe. But seals are not endangered along Greenland’s shores, so morally this is not the whole question. There are two others. One is about sustainability. Is it really better for the planet, or even for the planet’s animals, to eat factory-farmed birds that have been transported across the Atlantic than to eat locallycaught seal? Wasting energy transporting food is bad for the planet: causing Greenlanders to be entirely dependent on food that simply cannot be produced in Greenland is bad for Greenland. View across Greenland’s capital, Nuuk For many Greenlanders, chicken replacing seal is an imposition of European norms on a country where they are just not appropriate – which leads to the last question. What aspects of day-to-day life that we take for granted would others find bizarre? It can be taken further - what aspects of our life would others find as upsetting as we (or I) instinctively find hunting seals? It was normal for Norse to farm, for Thule to harpoon, for Danes to live in cities. Is normality anything more than a local invention? And what is the relationship between ‘normal’ and ‘sensible’ and ‘right’? Religious leanings: Erik’s dispute with his wife and its result in Viking heritage This time, the fjord is wide and bright, the sky royal blue, the sea pea-green, only the odd lump of white ice betraying its Greenlandic location. On the terrace of the youth hostel, a man lies stretched out in the sun. From its front door, two figures set out, chatting ladies in hiking boots. It is possible to overhear their conversation: one is an Italian cook, the other an English writer on the tracks of a Viking explorer. They talk about the others at the hostel: the Danish fishermen, the Japanese mother and son. They hurry: they are late. The road they are following is brick-red and winds along the side of the fjord, between the green fields and the few houses, over a bridge. Finally it climbs steeply, and the pair turn off it, towards a low wall with a high gate. On this wall, a lady sits, dressed in white: a long robe fastened with buckles at the shoulders, a Viking dress. The lady speaks: she starts to tell a story. *** View across the fjord at Qassiarsuk, the site generally identified as Brattahlid, where Erik settled in Greenland. The story told by Ingibjörg Gisladottir, storyteller, was about Erik the Red and his wife Thjodhild: this fjord was the site of Brattahlid, where Erik settled after colonising Greenland. Every summer, Ingibjörg works at the little church that has been reconstructed on this slope. This is one of the stories, from the Icelandic Sagas, that she tells. When Erik came to Greenland, he worshipped the old Norse gods: Thor and Odin and all. But his son, Leif, went away as a young man to Norway and converted to Christianity. Leif then brought Christianity to Greenland, and his mother was one of the first to convert. Erik, however, loathed the new religion. He refused to countenance its presence in his house but he did – eventually – allow Thjodhild to build a small church, just out of sight of their home. ‘Thjodhild’s Church – reconstruction at Qassiarsuk, South Greenland. The context of this is larger. In Iceland, in the year 1000, Christianity was officially adopted as the state religion. The decree was issued that it was impossible for two religions both to be official, though it was still allowed to practise pagan rites if nobody caught you. Erik had been in Greenland for fifteen years by then, but even in his time Christianity had been spreading through the land, challenging traditional beliefs. This was not merely a personal conflict: it reflected patterns of state politics. In the 1960s, the walls and graveyard of a small church were discovered in this bay, and archaeologists identified it as Thjodhild’s church. (For the record, there are those who dispute this, and certainly no way to prove it beyond doubt.) In the year 2000, the church – alongside a Norse longhouse and a traditional Thule house – was reconstructed. The church is just larger than large enough to stand up in: it is lined with still-fresh pine, and a driftwood cross by Greenlandic artist Aka Høegh rests above the altar. The front wall, mostly door, is also pine. The other three walls (the ones which left traces in the earth) are turf, and a low turf wall surrounds the whole. Ingibjörg explains that most of the reconstruction is down to imagination. She also tells the tale of the church’s opening, which was attended by several bishops. Because in Erik’s day the Church had not yet split into East and West, and further into Russian and Greek, Protestant and Catholic, Quaker and Methodist, this little church is ancestor to all today’s Christian faiths. This bay was the most westerly outpost of Christianity, for a long time. So the result of a quarrel between Erik and his wife has come to symbolise the unity of the Christian faiths, and what they hold in common. It is not claimed that those of Christian faith were united in Erik’s day – there had been many disputes and heresies already. Religion in general was even further from united. But the choice of those who reconstructed the little church was to focus on unity, not dispute, similarity, not difference. The church is visited by people from all over the world. Pine-scented, the little chapel is a place of calm, a place to come to rest. Conclusion: writer’s fever and the art of living it twice. She sits leaning against a stone, pad in hand, scribbling; she sits, cocooned in her sleeping bag, pencil moving, scribbling; she sits at table, menu pushed aside, eyes concentrated on the notebook, scribbling; she talks and questions and writes and writes; she pulls the pad out in the rain and scrawls until the paper is too wet to use; she chats casually to the driver of the car, catching his words as he speaks them; she turns the pages, sketches, writes panic lists of words that might describe a moment, writes and writes and writes… During my Churchill Fellowship my pencil and pad were never further than my knapsack, and my knapsack was never out of reach. Every day I spent hours writing: sudden minutes recording specific moments, long stretches remembering the events of an afternoon. Two pieces of advice were invaluable to me: both came from the same article by William Dalrymple on the BBC website.5 The first: write constantly. The atmosphere is in the detail, not just the visual but the heard, tasted, touched and smelt. It is the shape of the tree on the horizon, or the scent of the fish in the harbour, that brings life to a scene. The second: record dialogue at once – it is almost impossible to remember. At one level, following this advice was easy: I could notice a detail, laugh at a conversation and reach for my pad. But sometimes pulling out a notebook was not appropriate: say, when the customs official was pulling objects out of my bag. Imagine it: Official: So, how long are you staying in Iceland? Me: Three weeks. Official: And do you have any alcohol in your bag? 5 Getting started in travel writing by W Dalrymple, retrieved 2006 from http://www.bbc.co.uk/dna/getwriting/module16p - unfortunately at time of writing this seems no longer to be available online. Me: No. Official: I need to search your bag. Please come through here. Me: OK. And do you mind if I pull out a notebook and write down everything you say? Official: Er – what? Please open your bag. Me: Sorry, I’m still writing down what you said… what did you say? Official: Please stop writing and open your bag. Me: Hold on, hold on… you see, each time you say something I have to write it down… Even the obvious solution, a dictaphone, was not as good as a notebook – a dictaphone could not record gestures, or facial expressions, or my own internal responses. The solution proved to be a sort of very intense concentration, an attempt to learn by heart each scene, each moment of each day. Taking photos helped too, allowing me to add in details that I had forgotten by the time I recorded the day. Collecting paraphernalia, leaflets and books so that solid information did not need to be recorded, meant that more effort could be expended on people and places. But the intense concentration on people added to my own self-consciousness. I noted how I reacted to people’s chance remarks, and how they reacted to mine, until I was nervous of speaking unless I had thought through my words thoroughly beforehand. I noted gestures until I was so aware of my own that I watched and censured every one. I became so aware of the world and of my own path through it that rather than watching through my own eyes, I often felt I was watching myself move, a small figure tracing a path across the planet’s surface. An intense process, to live life once with extreme concentration, and then a second time, internally, remembering every detail to record it. Slight madness? If so, it has faded for now. The first result of my Fellowship was two tightly-written notebooks of impressions, conversations, colours, scents and sounds. As can be seen from the four mini-essays that form this Report, my experiences were richly varied, full of stories, full of surprises. My Fellowship did not only teach me about writing, about Vikings or about Erik the Red, though it taught me much about all. I had opportunities to see the world from the perspective of people entirely unlike myself – people who consider it easy to cross the Atlantic in a Viking ship; people who find it more natural to eat seal than to eat beef. And more than anything else I may pass on to peers, colleagues, readers – more than details of history or quirks of other cultures – I would hope that this consciousness of other ways of thinking, other normalities, other passions, will be what makes this Fellowship ‘of value to the UK’ as a Churchill Fellowship is intended to be. It has already made it invaluable to me.