skraelings

advertisement

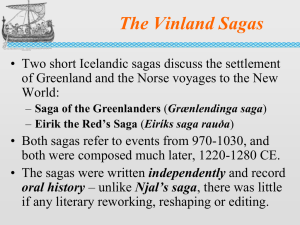

Viking Exploration Scandinavian explorers began sailing west in the North Atlantic as early as the ninth century. Similar to traditions of exploration that emerged in southern Europe, Scandinavian explorers were undertaking quests for knowledge, trade, and conquest. These motivations led them further into what would later be called the New World. The Vikings, in particular, pushed far into the unknown territories of the West. In 870 they joined Irish colonists in settling Iceland. One of these Viking colonists, Erik Thorvaldsson, also known as Erik the Red (950–1003), discovered Greenland in 982, after being exiled from Iceland. Three years later he founded two colonies there with five hundred settlers, and the colonies soon began to thrive. The following year a would-be settler of Greenland named Bjarni Herjólfsson (c. 960–c. 1022) was blown off course on his way to the new colony. He ended up sailing far west of his intended destination, sighting the coasts of Labrador and Newfoundland. When Herjólfsson finally made it to Greenland, he told tales of the new land he had seen. Erik the Red’s teenage son, Leif Eriksson, paid close attention to these tales, particularly Bjarni Herjólfsson’s description of the abundant tall timber—an invaluable resource for shipbuilding—growing in these lands. Eriksson, also itching to get out from under his father’s stern rule, set sail in Bjarni Herjólfsson’s old ship, bound for the new lands, around 1000. His discoveries would mark the farthest expansion of Europeans for another five hundred years, until the voyages of Christopher Columbus (1451–1506) to the Caribbean. "Leif Eriksson Explores Canada: 1000." Global Events: Milestone Events Throughout History. Ed. Jennifer Stock. Vol. 6: North America. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale, 2014.World History in Context. Web. 7 May 2014. The Family Business Erik the Red was born in Norway near the town of Stavanger. His father, Thorvald Asvaldsson, became involved in a blood feud and killed a man. As was usual for the time, he was sentenced to exile in Iceland, which had first been settled by the Norwegians starting in the 870s. The family moved to a remote part of western Iceland. After he was grown and married, Erik moved to another part of Iceland where he too became involved in a blood feud and killed two of his enemy's sons. As punishment, he was banished overseas for a period of three years. Erik had heard about the voyages of a man who had found a group of small islands west of Iceland and said that he had seen a much larger land beyond that. Erik announced that he was going in search of this land. With a group of men he sailed due west from Iceland in the year 982 and discovered a new land he called Greenland. By this time, the term of Erik's banishment from Iceland was complete. After exploring Greenland for a few years, he sailed back around the southern tip of Greenland and returned safely to Iceland in the summer of 985. On his return, the blood feud with his neighbors started up again. Erik then began to promote the colonization of his new found land, calling it "Greenland," thinking that would make it more appealing. He left Iceland in 986 with 14 ships that carried 400-500 people as well as domestic animals and household goods. In the year 999, Erik's son, Leif Eriksson, pioneered the first direct route to Norway from Greenland. While in Norway, Leif converted to Christianity and brought back the first missionary with him to Greenland. This did not please Erik, who remained true to the old Viking religion. When Leif made his trip to Vinland in 1001 or 1002, Erik wanted to go with him but fell off his horse on the way to the ship and injured his leg. Erik the Red died sometime during the winter of 1003-1004. Ironically, he was buried on the grounds of what became the Christian cathedral at Brattahlid. He left behind three sons—Leif, Thorvald, and Thorsteinn—and an illegitimate daughter named Freydis, noted for her habit of getting into arguments. She married a man named Thorvard, and they became the richest but least popular couple in the Greenland settlement. The Norse Greenland settlements prospered for a while, but then they were afflicted by a changing climatic pattern that made the weather much colder and no longer suitable for European farming practices. The increased ice in the ocean also made communication with Iceland more difficult. The last recorded voyage between Iceland and Greenland was made in 1410, although it is probable that there were some later trips. The Inuit advancing from the north are thought to have overwhelmed the Western Settlement around 1350. The last Norsemen in the Eastern Settlement probably disappeared sometime in the early 16th century. "Erik the Red." Explorers & Discoverers of the World. Gale, 1993. World History in Context. Web. 7 May 2014. Western Expansion The Vikings also began to build settlements in northwestern Europe. In Ireland, Scotland, the Faroes, Orkney and Shetland Islands, and northeastern England, the Vikings mingled and intermarried with the people adopting their languages and customs. In France, a district in the lower Seine River basin was officially granted to them as the duchy of the Northmen (Normandy) in 911. There, too, they assimilated well with the local inhabitants, also adopting their language and many of their customs. Yet, some Vikings were unsatisfied with these settlement plans. Perhaps out of a sense of adventure, or maybe, as in the case of the most famous Viking explorer, Erik the Red, out of a sense of wanting to be an outlaw, some Vikings chose to sail farther from their traditional sites of raiding, conquest, and colonization. Iceland, an island northwest of the Faroes Islands, had been discovered around 874, with permanent Viking settlement taking place a short time afterward. Despite its name, the island is quite habitable, with significant thermal activity that maintains a mild climate mild and creates land suitable for agriculture. However, the same cannot be said for Greenland. Discovered in 982 by Erik the Red, it is surrounded by ice-choked waters and has few habitable farmlands or pastures. Viking colonies survived there into the fifteenth century, when, for some reason, the settlers abandoned them and disappeared. "The Vikings as Explorers and Colonists." World Eras. Ed. Jeremiah Hackett. Vol. 4: Medieval Europe, 814-1350. Detroit: Gale Group, 2002. 43-46. World History in Context. Web. 7 May 2014. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------But Erik the Red’s son, Leif Eriksson, led a successful voyage resulted in what some consider the earliest European exploration of North America. The first land his expedition encountered was a barren, rock-strewn place that the explorers named Helluland, now thought to be Baffin Island in the Canadian territory of Nunavut. Next the explorers came upon a land of great timbers that they called Markland (Forest Land), in what is now thought to have been Labrador. Finally, the expedition landed in a temperate, wooded area they called Vinland (Vine Land) after grapes were discovered growing there in the wild. (The Middle Ages was a time of increased global temperatures during which grapes grew as far north as Newfoundland.) The expedition most likely stayed in Vinland for the winter, in present-day Newfoundland, then returned home with a load of timber and trade goods, earning Eriksson the nickname of Lucky Leif. "Leif Eriksson Explores Canada: 1000." Global Events: Milestone Events Throughout History. Ed. Jennifer Stock. Vol. 6: North America. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale, 2014.World History in Context. Web. 7 May 2014. Leif’s Legacy Although historians had known about two sagas—epic poems that blended Norse history and myth—that recounted exploration and settlement of a previously unknown land in the West, the tales had been discounted. L'Anse aux Meadows and related findings proved that the myths were based on fact. The Norse had sailed to and settled in North America nearly five centuries before Columbus inaugurated the so-called Age of Discovery. Unlike Columbus and those who came after him, the exploits of Eriksson and his followers failed to establish a permanent presence in the New World. Various factors may have conspired to cause their temporary stay in North America, chief among which was perhaps the lack of economic and population pressures comparable to those that propelled European colonization from the sixteenth century onward. Another factor that might have curtailed the impact of the Norse discovery of the Americas is that, unlike later Europeans, the Vikings were not surprised to find land to the west. Their cosmology imagined a great world ocean surrounded by a ring of islands and land masses. The Norse people were great sailors during the Middle Ages, and they routinely made discoveries. Expanding from their homeland in Scandinavia starting during the eighth century, they discovered and colonized the Shetland and Faroe Islands and the Hebrides; settled in presentday Scotland, Ireland, northern England, and northern France; and discovered and colonized Iceland and Greenland. Due to the limitations of Viking ships, which were swift and durable but could not carry much cargo or crew, these waves of discovery and settlement took place in a series of steps or jumps across the North Atlantic. Conflicts between Eriksson and his father delayed any immediate return voyage to Vinland. Eriksson sailed for Norway instead, hoping to curry favor with the king. Instead, he returned a Christian, with missionaries in tow, and settled into his role as leader of the Greenland colonies in the wake of his father’s death in 1003. Further explorations fell to Eriksson’s younger siblings. Eriksson’s brother Thorvald sailed to Vinland in 1003 to establish a colony but was killed two years later in skirmishes with the local natives, whom the Vikings called skraelings. The first permanent colony in Vinland was not established until 1010, when Leif’s brother-in-law brought his wife and other women with him on an expedition. Snorri Thorfinnsson, in approximately 1011, became the child the first European born in the Americas. Trade with the local skraelings was established, but disaster soon befell the colony when Eriksson’s half-sister Freyda, who had come to Vinland to form a trading partnership with two men, murdered her business partners and their families in what was either an attempt at a double-cross or a case of cabin fever brought on by the winter. Whatever the cause, Freyda returned to Greenland and was forgiven by Eriksson. Shortly after this incident, relations with the natives deteriorated, and the Vinland settlement ceased to exist. "Leif Eriksson Explores Canada: 1000." Global Events: Milestone Events Throughout History. Ed. Jennifer Stock. Vol. 6: North America. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale, 2014.World History in Context. Web. 7 May 2014. Global Impact of the Vikings In the centuries to come, Eriksson’s accomplishments would fade from notice, dismissed as legend, and Italian explorer Christopher Columbus would be regarded as the first European in North America. But in 1960, archaeologists working in Canada made a startling discovery: very strong evidence of European settlement in Newfoundland, which disproved the traditional narrative of the discovery of the New World by Columbus. The site, L'Anse aux Meadows, quickly became world famous. The settlement seemed to have been like a trading post, perhaps a stopping-off point for ships sailing farther south. The precise location of the main Viking colony in Vinland, as the Norse called the new land, remains a subject of controversy. Further archaeological discoveries, including a Norwegian coin found at an Indian hunting and fishing camp in Maine and dating to the mid-eleventh century, testify to extensive trade networks and a Viking presence in the New World over several decades, but details remain limited. The challenges faced by the Vinland colonists—isolation, hostile natives, small numbers, and limited resources—were not unlike those faced by European colonizers of the Americas five hundred years later. Many European colonies failed just as Vinland had. However, unlike Vinland, new colonies were founded in their place. The Norse gave up on Vinland, because there was no great drive to colonize a hostile land so far from the Viking homeland. Additionally, the Norse did not enjoy a technological advantage over the skraelings, nor did they arrive bearing deadly diseases to depopulate the countryside, both key factors in later European colonial success. Most important, perhaps, Eriksson and his kin sailed to Vinland on their own initiative, without the backing of a powerful nation-state. Their opportunities for successful exploitation were limited. There was no great spice trade to motivate explorers to keep driving ahead in their search for a passage to the Indies. To other Vikings the natural resources of Vinland would have proven a poor incentive when similar resources could be secured much closer to home. Ultimately the discovery of a New World to the west would live on in Norse oral tradition for centuries, nearly forgotten until present-day archaeologists unearthed evidence that the legend had its basis in fact. "Leif Eriksson Explores Canada: 1000." Global Events: Milestone Events Throughout History. Ed. Jennifer Stock. Vol. 6: North America. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale, 2014.World History in Context. Web. 7 May 2014.