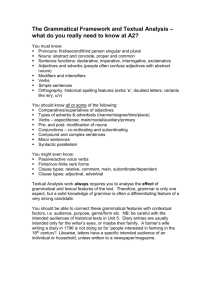

Universal Sentence Structure

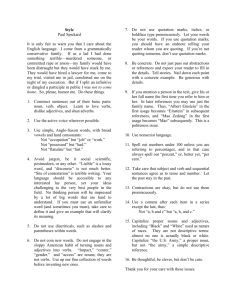

advertisement