“How am I doing?” - assessment and feedback to learners

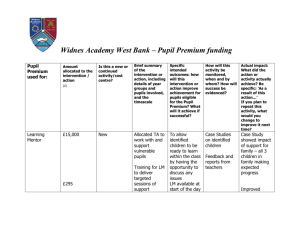

advertisement