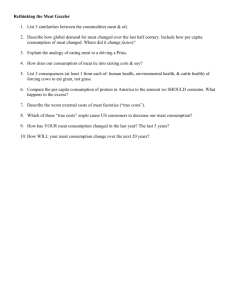

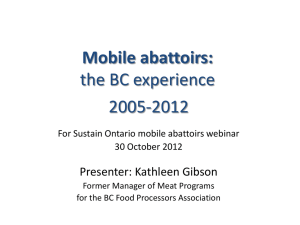

Proposal for a meat inspection service in South Africa for public

advertisement