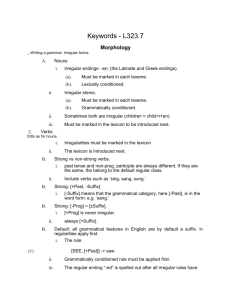

Berent et al., The nature of regularity and irregularity

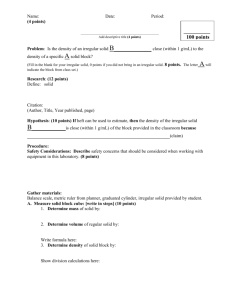

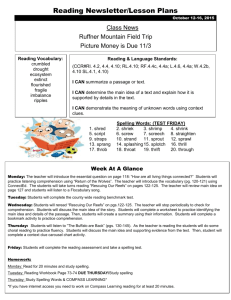

advertisement