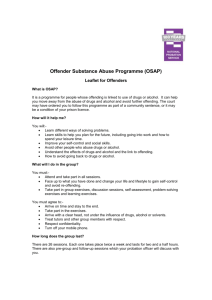

Probation Revocation

advertisement