Cyclin specificity: how many wheels do you

advertisement

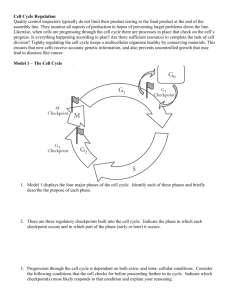

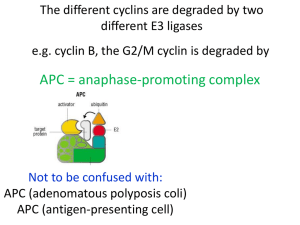

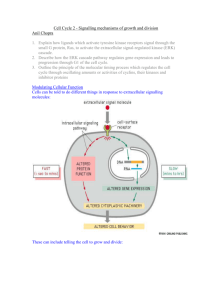

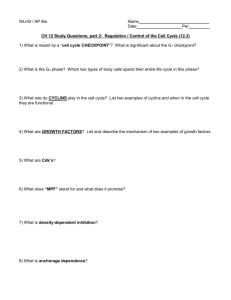

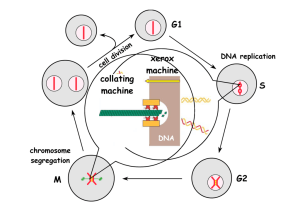

COMMENTARY 1811 Cyclin specificity: how many wheels do you need on a unicycle? Mary E. Miller and Frederick R. Cross* The Rockefeller University, 1230 York Ave., New York, NY 10021, USA *Author for correspondence (e-mail: fcross@rockvax.rockefeller.edu) Journal of Cell Science 114, 1811-1820 © The Company of Biologists Ltd Summary Cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) activity is essential for eukaryotic cell cycle events. Multiple cyclins activate CDKs in all eukaryotes, but it is unclear whether multiple cyclins are really required for cell cycle progression. It has been argued that cyclins may predominantly act as simple enzymatic activators of CDKs; in opposition to this idea, it has been argued that cyclins might target the activated CDK to particular substrates or inhibitors. Such targeting might occur through a combination of factors, including temporal expression, protein associations, and subcellular localization. Introduction The major events of the eukaryotic cell cycle depend on the sequential function of cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs; Levine and Cross, 1995). CDK catalytic activity is dependent upon physical association with cyclin regulatory subunits (De Bondt et al., 1993; Jeffrey et al., 1995). In animals, multiple CDKs exist and are activated by multiple cyclins. The many different complexes make analysis in animal cells difficult. In budding yeast, one CDK, Cdc28p, is present and activated by different cyclins at different cell cycle positions (Fig. 1; Cross, 1995; Nasmyth, 1996). A single CDK also functions in cell cycle control in fission yeast (Stern and Nurse, 1996). Although the general principles of cell cycle control in yeast and higher eukaryotes are similar, the single CDK makes analysis simpler in yeast, and for this reason we focus primarily on the yeast systems. We refer to results from animal systems when clear comparisons can be made. Different cyclin-CDK complexes are required for distinct cell cycle events. In budding yeast, at cell cycle initiation, the CDK Cdc28p is activated by the Cln cyclins; at initiation of DNA replication Cdc28p is activated by the B-type Clb5p and Clb6p cyclins, and at mitosis Cdc28p is activated by the B-type Clb1p, Clb2p, Clb3p and Clb4p cyclins. Note that these statements on the biological roles of different cyclins are based mainly on knockout phenotypes. Since the different cyclins are under distinct transcriptional and proteolytic controls, the knockout phenotype does not distinguish between the absence of any (generic) cyclin at a given time and the absence of a specific cyclin. The question of whether the different cyclin proteins are intrinsically specialized (apart from distinct regulation of protein abundance) is one of the main subjects of this Commentary. regulated cyclin expression. The mitotic B-type cyclins are degraded during or at the end of mitosis by the proteosome, after ubiquitination by the highly conserved anaphasepromoting complex (APC; Irniger et al., 1995; King et al., 1996; Zachariae et al., 1996). In budding yeast this control is somewhat redundant with accumulation of the Sic1p inhibitor of Clb-Cdc28p kinase activity (Schwab et al., 1997; Schwob et al., 1994). It has been proposed that the resulting oscillation of Clb-Cdc28p kinase activity is required for alternation of DNA replication and mitosis (see below). The budding yeast G1 cyclins (Cln proteins) are highly unstable owing to the action of non-APC ubiquitinating Skp1p–Cdc53p–F-box protein complex (SCF; Bai et al., 1996; Willems et al., 1996). G1 cyclin instability is not thought to be cell cycle controlled. Instability nevertheless imparts biological significance on transcriptional control of G1 cyclins, since the abundance of highly unstable proteins closely reflects recent transcriptional activity. Yeast cyclin genes are transcriptionally controlled. The G1 cyclin genes CLN1 and CLN2 and the S-phase-acting CLB5 and CLB6 are activated by Cln3p-Cdc28p activity at cell cycle Start (see below). CLB3 and CLB4 come on later for unknown reasons. CLB1 and CLB2 (Clb2p is the major mitotic B-type cyclin) are activated in a positive feedback loop involving Mcm1p, Ndd1p, Fkh1p and Fkh2p, as well as Clb2p (Althoefer et al., 1995; Amon et al., 1993; Koranda et al., 2000; Kumar et al., 2000; Pic et al., 2000; Zhu et al., 2000). CLN3 expression is moderately periodic owing to transcriptional activation late in the cell cycle (McInerny et al., 1997). Regulation of cyclin abundance Control of cyclin gene transcription and cyclin proteolysis governs cell cycle progression in many contexts in all eukaryotes and gives rise to successive waves of cell-cycle- Key words: Cyclin, CDK, Cell cycle, Targeting, Phosphorylation Two central questions about cell cycle control by CDKs: why does it matter that CDK activity oscillates and does it matter which cyclin activates a CDK? Coupling between CDK activity cycles and periodic DNA replication A central aspect of cell cycle control is the alternation of DNA 1812 JOURNAL OF CELL SCIENCE 114 (10) Cell growth Mating-factor pathway Cln3p Clb3p, Clb4p Cln1p, Cln2p Clb5p, Clb6p Clb1p, Clb2p Fig. 1. Cyclins and control of the budding yeast cell cycle. All cyclins shown interact with the Cdc28p CDK. The Cln G1 cyclins are required for cell cycle Start, which entails bud emergence, inhibition of the mating factor pathway and activation of Clb-Cdc28p complexes. Cln3p is primarily a transcriptional activator of CLN1, CLN2, CLB5 and CLB6 and other genes (Breeden, 1996; Dirick et al., 1995; Levine et al., 1996; Stuart and Wittenberg, 1995; Tyers et al., 1993). The CLN1 CLN2 gene pair may act directly to drive bud emergence and morphogenesis, as well as Clb-Cdc28p activation (reviewed in Cross, 1995). Cell cycle Start is modulated by cell growth and by the mating-factor pathway, probably through direct effects on Cln-Cdc28p function (Cross, 1995; Jeoung et al., 1998; Nasmyth, 1993; Nasmyth, 1996). Clb-Cdc28p complexes are directly responsible for activation of DNA replication and mitotic initiation (Nasmyth, 1996). Shaded circles represent nuclei undergoing DNA replication. replication and mitosis (Rao and Johnson, 1970; Stillman, 1996). A model was proposed to account for this alternation (Nasmyth, 1996). High Clb-Cdc28p kinase activity was proposed to inhibit loading of proteins required for origin formation. Once replicated through direct use or passive replication, an origin was proposed to ‘unload’, preventing another initiation from this origin until reloading. Thus, cells locked in a low Clb-Cdc28p activity state will not replicate, because Clb-Cdc28p activity is required for replication (Schwob et al., 1994), whereas cells locked in a high ClbCdc28p activity state will not re-replicate, because they cannot reload replication origins. The model thus proposes an obligatory oscillation of Clb-Cdc28p kinase activity for consecutive and alternating rounds of mitosis and replication. Independently of the requirement for low Clb-Cdc28p activity for reloading origins, a drop in Clb-Cdc28p activity is required for completion of mitosis. Cells in which Clb2pCdc28p activity is maintained at a high level by overexpression of undegradable Clb2p block in anaphase; separated chromosomes remain on a long anaphase spindle, and cells fail to complete cytokinesis or nuclear division (Surana et al., 1993). As described below, a similar model was proposed based on work in fission yeast (Stern and Nurse, 1996). In this model, a moderate level of the B-type cyclin-CDK complex activity is required to begin S phase, and an increased level is required to trigger mitosis, thus ensuring that DNA replication occurs before mitosis. Again, high activity is proposed to inhibit the loading of proteins on origins, so that, once replicated, they will not replicate again and B-type cyclin-CDK activity must drop for cells to exit mitosis (Stern and Nurse, 1996). A proposal for the minimal cell cycle It is likely that the cell cycle requires an alternation between a low B-type cyclin-Cdk kinase activity state and a high kinase activity state, and this must be coupled to an alternation in the activity of the APC ubiquitinating machinery (Fig. 2A). Active Cdk stimulates DNA replication and spindle assembly, and may also promote activation of the form of the APC that is active with Cdc20p. Cdc20p is a ‘specificity factor’ that induces the APC to ubiquitinate Pds1p and some Clb proteins in budding yeast (Rudner et al., 2000; Rudner and Murray, 2000). The low Cdk activity state is largely self-reinforcing in budding yeast, because it is characterized by accumulation of the Sic1p inhibitor of Clb kinase, by high activity of Hct1pdependent Clbp proteolysis and by low CLB transcription. Hct1p is a Cdc20p relative that is predominantly involved in Clb2p proteolysis in the low Clb activity state. All of these conditions are reversed by the Cln kinases, since they are immune to Sic1p and Hct1p, and their transcription is independently controlled. Cln-dependent phosphorylation of Sic1p leads to its degradation, and Cln-dependent phosphorylation of Hct1p may lead to its inactivation (Amon, 1997; Visintin et al., 1998; Zachariae et al., 1998). The high Clb activity state is also self-reinforcing, even without Cln kinase activity, because Sic1p and Hct1p phosphorylation can be carried out by Clb kinase activity, and Clb2p, at least, stimulates its own transcription (see Fig. 2B; Amon, 1997; Amon et al., 1993). CDK-cyclin activity: quantitative vs qualitative models for specific functions There are two extreme viewpoints on the question of functional specialization of cyclins: the particular cyclin might be irrelevant to function except as a general activator of CDK enzymatic activity (Stern and Nurse, 1996); alternatively, cyclin identity might be essential for interaction of a CDK with appropriate (cyclin-specific) targets. Intermediate scenarios are possible, in which some cell cycle events require specific cyclins for targeting but others simply require a given level of activated CDK and are independent of the activating cyclin. The case against the importance of cyclin specificity On the basis of work in fission yeast, it has been proposed that there is no requirement for cyclin-specific targeting of CDK activity to appropriate substrates (Stern and Nurse, 1996). Although there are multiple cyclins in this organism, deletion of all but a single cyclin, Cdc13p, yields a viable strain with coordinated DNA replication and mitosis (Fisher and Nurse, 1996). Although strains lacking other cyclins cig1, cig2 and puc1 exhibit a significant delay in initiation of replication, this delay can be eliminated by removal of the Rum1p inhibitor (Martin-Castellanos et al., 2000). On the basis of these observations, it was proposed that different cell cycle events occur as a consequence of the accumulation of different quantities of active cyclin-CDK complex. DNA replication was proposed to have a lower threshold for CDK activity than does mitosis; as with the model discussed above (Nasmyth, 1996; Stern and Nurse, 1996), it was proposed that high CDK activity also blocks reloading of replication origins to block re-replication before mitosis. According to this ‘quantitative’ model, a periodic rise and fall Cyclin specificity: how many wheels do you need on a unicycle? 1813 of CDK activity can yield qualitatively different responses at specificity could be due to extrinsic regulatory controls that different levels. The observation that (as in budding yeast) large differ for different cyclins. For example, the APC degrades numbers of different cyclins have apparently distinct biological mitotic (Clb) cyclins but not G1 (Cln) cyclins, and the Sic1p roles could simply be due to the phased activation of different inhibitor and the Swe1p inhibitory kinase inhibit Clb-Cdc28p genes, which have been selected during evolution for their but not Cln-Cdc28p complexes (Booher et al., 1993; Irniger et ability to achieve the appropriate overall quantity of activated al., 1995; King et al., 1996; Schwob et al., 1994). In contrast, CDK. the inhibitor Far1p, when activated by the mating-factor In fission yeast, loss of Cdc13p-Cdc2p activity (either pathway, inhibits the G1 Cln-Cdc28p but not Clb-Cdc28p through deletion of cdc13 or overexpression of the Cdc13pcomplexes (Gartner et al., 1998; Jeoung et al., 1998; Peter and Cdc2p inhibitor rum1+) induces multiple rounds of reHerskowitz, 1994). In fission yeast, the Rum1p inhibitor replication of DNA (Hayles et al., 1994; Sanchez-Diaz et al., inhibits the kinase activity of Cdc13p-Cdc2p and Cig2p-Cdc2p 1998). This could fit with the idea of high cyclin-Cdk activity complexes, whereas Puc1p-Cdc2p and Cig1p-Cdc2p blocking reuse of origins of replication. The model still appears complexes are insensitive to inhibition. Additionally, Rum1p to require some mechanism to allow cyclical inactivation of the itself is phosphorylated and targeted for degradation by Puc1premaining functional cyclins in these contexts (since otherwise, Cdc2p and Cig1p-Cdc2p complexes (Benito et al., 1998). replication origins should remain unloaded after one round of Thus a biological requirement for a specific cyclin could be replication). This has not been addressed experimentally to our due not to differences in output of different cyclin-CDK knowledge. complexes but rather to differences in regulatory input to the According to this view, the apparent functional specificity of cyclin-CDK system. For example, the specific requirement for different cyclins (based on deletion analysis) could simply be due to differences in the timing of cyclin expression. In this case, the cyclin-CDK complex would be available only Origin use at certain times in the cell division cycle and Origin Spindle Anaphase Telophase (DNA therefore have access to only a subset of loading assembly substrates. Certainly, a correlation between replication) expression patterns and the timing of functions exists (as described above). The question becomes, in the absence of this temporal regulation, do cyclins continue to Clb kinase confer functional specificity on the CDK? Overexpression of the B-type cyclin CLB5 Hct1p Pds1p can rescue deletion of the three G1-type Cln kinase Cdc20p Sic1p cyclins (Epstein and Cross, 1992). Additionally, constitutive overexpression of Hct1p, the B-type cyclin CLB1 rescues a strain Cdc20p lacking all remaining B-type cyclins (Haase (APC activators) Cell growth Cdc14p and Reed, 1999). In Drosophila, no single deletion of cyclin A, cyclin B or cyclin B3 caused striking defects, but deletion of both cyclin B and cyclin B3, or of cyclin A and cyclin B3, gave mitotic defects (Jacobs et al., Cln 1998), suggesting substantial overlap among Low Clb High Clb the function of these cyclins. Such results, activity Cdc14p, activity coupled with the fact that, in fission yeast, Cdc20p cdc13 is sufficient as the sole B-type cyclin (Fisher and Nurse, 1996), are not consistent High [Sic1p] Low [Sic1p] with the idea that cyclin targeting is essential Hct1 active Hct1p inactive for appropriate CDK activity. A dramatic result suggesting that specific Low CLB High CLB cyclins are not required for targeting Cdk transcription transcription activity was the finding that appropriate ‘activating’ mutations in the budding yeast Fig. 2. The minimal cell cycle. (A) Regulatory machinery responsible for the minimal Cdc28p CDK eliminate all detectable cyclin cell cycle. Note that inhibition (indicated by a flat line) occurs by multiple mechanisms: requirements for cell cycle Start, which stoichiometric inhibition, phosphorylation, or proteolysis due to ubiquitination. Activation (indicated by an arrow) is presumably achieved by phosphorylation in some normally requires at least one Cln cyclin (Fig. cases and by dephosphorylation in others. See recent reviews and papers for more 1). However, such mutations did not bypass information (Cross, 1995; Deshaies, 1997; Nasmyth, 1996; Rudner et al., 2000; Rudner cyclin requirements later in the cell cycle and Murray, 2000; Zachariae and Nasmyth, 1999; Zachariae et al., 1998). (B) The (Levine et al., 1999). minimal cell cycle as a Clb activity cycle, in which transitions between the low Clb Even in cases in which a specific cyclin activity state and high Clbp activity state are regulated by Cln kinase, Cdc14p and requirement is demonstrated, cyclin Cdc20p. A B 1814 JOURNAL OF CELL SCIENCE 114 (10) budding yeast Cln cyclins to reverse the low Clb activity state discussed above (Fig. 2A) is probably due to immunity of the Cln-Cdc28p kinases to Clb-inhibitory mechanisms, rather than to different abilities of active Cln-Cdc28p complexes vs ClbCdc28p complexes to carry out some functions. This is evidenced by the ability of Clb-Cdc28p complexes to maintain the high-Clb activity state once it is established (see above), as well as by the bypass of the Cln requirement by CLB5, or certain CDC28 mutations (Epstein and Cross, 1994; Levine et al., 1999). Similarly to the situation with Sic1 and Cln cyclins in budding yeast, the Cig1p and Puc1p cyclins of fission yeast are immune to the Rum1p inhibitor, but phosphorylate Rum1p and trigger its degradation (Benito et al., 1998). It is not clear, though, whether the Cdc13p or Cig2p complexes are able to overcome Rum1p inhibition if the cyclin-Cdk complexes are present at a high enough level. Another interesting example of input specificity could be the case of the viral cyclins that can activate Cdk6. The viral cyclin-Cdk6 complexes are resistant to the INK4 and Cip/Kip families of inhibitors and so allow Rb phosphorylation to occur independently of the presence of these inhibitors (Swanton et al., 1997). These viral cyclins may also alter output specificity in this system, since the substrate specificity of the viral cyclin-Cdk6 complexes is thought to be higher than that of endogenous cyclin-Cdk6 complexes (Chang et al., 1996; Godden-Kent et al., 1997; Jung et al., 1994; Swanton et al., 1997). Evidence in favor of intrinsic cyclin functional specialization In some cases, cyclin-dependent events are not rescued by ectopic expression of different cyclins under conditions in which differences in regulatory input appear to have been eliminated. Repression of the mating factor response pathway by CLN2 overexpression was not duplicated by constitutive CLB5 or CLN3 overexpression (Oehlen and Cross, 1994). The Clb2p mitotic B-type cyclin is unable to trigger transcription of genes normally activated by Cln3p and in fact inhibits their expression (Amon et al., 1993), whereas the Clb5p B-type cyclin might activate expression of these genes (Li and Cai, 1999; Schwob and Nasmyth, 1993). Overexpression of the CLN genes or of CLB5, but not of CLB3 or CLB4, eliminates heat-shock-induced G1 arrest, owing to a specialized ability of CLB5p to activate CLN1 and CLN2 transcription (Li and Cai, 1999). The function of CLB5 in spindle morphogenesis or premeiotic DNA replication cannot be rescued by overexpression of CLB2 (Segal et al., 1998; Stuart and Wittenberg, 1998). CLN and mitotic cyclins have essentially opposing effects on budding yeast morphogenesis, and these effects are exacerbated by overexpression (Lew and Reed, 1993). CLB5 is able to promote the activation of early and late origins of replication, whereas CLB6 is able to activate only early origins (Donaldson et al., 1998; in this case, however, the pattern of expression of Clb6p has not been shown to be the same as that of Clb5). Spindle pole body (SPB) duplication is a multistep process both positively and negatively regulated by the cyclin-Cdc28p complexes. The Cln-Cdc28p complexes are able to trigger SPB duplication during G1 phase, whereas Btype cyclin-Cdc28p complexes carry out maturation of SPBs. B-type cyclin-Cdc28p complexes are also able to inhibit reduplication of SPBs, ensuring that SPB duplication occurs only once per cell division cycle (which is similar to models for control of DNA replication; Haase et al., 2001). With respect to cyclin specificity, it was shown that even overexpressed CLN2 or CLB5 could not block SPB reduplication, which suggests that this function is intrinsically specific to CLB1-CLB4 (Haase et al., 2001). In fission yeast, the G1-type cyclin-CDK complex Puc1p-Cdc2p cannot induce S phase, unlike the B-type cyclin-Cdc2p complexes (Fisher and Nurse, 1996). In higher eukaryotic cells, cyclin D2 and cyclin D3, but not cyclin D1, prevent differentiation of 32D myeloid cells in response to granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (Kato and Sherr, 1993). These data suggest that some CDKdependent events require specific cyclin-CDK complexes or at the least that specific cyclins strongly potentiate some CDKdependent events. To demonstrate that cyclin proteins confer functional specificity to CDKs, cyclin-coding sequences have been placed under control of a distinct cyclin promoter. In this way, a direct functional comparison of the two cyclins can be made independently of differences in expression patterns. This approach was first used to compare the functional specificities of the G1-type cyclins Cln2p (representative of the highly homologous CLN1/CLN2 gene pair) and Cln3p (Levine et al., 1996; Valdivieso et al., 1993). Previously, functional analysis of Cln2p and Cln3p had revealed that they support cell cycle entry by distinct mechanisms; Cln3p is responsible for transcriptional activation of G1 transcripts, including CLN1 and CLN2 (Dirick and Nasmyth, 1991; Koch and Nasmyth, 1994; Stuart and Wittenberg, 1995). Cln2p is required for additional G1 events, including bud emergence and activation of Clb-CDK complexes (Benton et al., 1993; Cvrcková and Nasmyth, 1993; Lew and Reed, 1993). The intrinsic functional specificity of Cln2p, compared with that of Cln3p, is demonstrated by the fact that Cln2p and Cln3p differ in their support of viability in certain genetic backgrounds, even when both are expressed from the CLN3 promoter (which produces relatively constitutive, low levels of expression; Levine et al., 1996). These data indicate that differences in the timing or the levels of expression of CLN2 and CLN3 do not account entirely for their functional specificity. More recent studies reveal that Cln2p and Cln3p are primarily localized to distinct subcellular compartments, and that their localization contributes to their functional specificity (Miller and Cross, 2000; see below). Despite the clear differences in functional specificity between Cln3p and Cln2p, both are independently able to support cell cycle initiation. This is probably due to the existence of parallel pathways backing up certain aspects of G1 cyclin function. Thus Cln3p is ‘aided’ by proteins that might mimic some aspects of Cln2p function (Levine et al., 1996). In the case of Cln2p, transcripts normally activated by Cln3p are delayed but eventually are produced at reasonably high levels, possibly with the aid of Bck2p (Levine et al., 1996). Bck2p works in parallel with (although independently of) Cln3p to activate transcription (Di Como et al., 1995; Epstein and Cross, 1994). Similar conclusions have been drawn about cyclin D1 and cyclin E in mice. Geng et al. found that phenotypes associated with the cyclin D1 knockout were rescued by replacement of the coding sequence of cyclin D1 with that of cyclin E (Geng et al., 1999). Although this result suggested that cyclin E and cyclin D1 are functionally redundant, a closer examination of Cyclin specificity: how many wheels do you need on a unicycle? specific cyclin-D1-dependent events that occur during normal cell cycle progression showed that cyclin E did not rescue these events but instead bypassed the requirement for cyclin D1 during cell cycle progression. These results are reminiscent of the relationship between Cln3p and Cln2p in which either cyclin can support entry into the cell cycle, but do so by different mechanisms. Cyclin specificity that is independent of differences in expression patterns has also been demonstrated for B-type cyclins in budding yeast. CLB5 and CLB6 are expressed earliest and implicated most directly in regulation of DNA replication, especially of late-acting origins in the case of Clb5p (Donaldson et al., 1998; Epstein and Cross, 1992; Schwob and Nasmyth, 1993). CLB1 and CLB2 are expressed later and are involved in regulation of mitosis (Surana et al., 1993). Replacement of the coding sequence of CLB5 with that of CLB2 (so that CLB2 is expressed from the CLB5 promoter) can rescue inviability due to deletion of CLB1 and CLB2 but poorly promotes the onset of DNA replication. This effect appears to be largely independent of differences in Clb protein expression (Cross et al., 1999). Overexpression of a Clb2p mutant lacking its destruction box (which is therefore immune to APC-mediated ubiquitination and proteolysis) results in inhibition of mitotic exit (Ghiara et al., 1991; Surana et al., 1993). Overexpression of destruction-box-deleted Clb5p to similar levels failed to inhibit mitotic exit, although it did appear to block DNA replication in the next cell cycle (Jacobson et al., 2000). This suggests that Clb2p is much more efficient at blocking mitotic exit, whereas both Clb2p and Clb5p may block reloading of origins of replication (see above and Fig. 2A). A special ability of Clb5p to prevent Clb2p-Cdc28p inactivation late in the cell cycle was inferred from the result that, in the absence of Cdc20p and Pds1p, Clb5p plays a unique role in blocking mitotic exit (Shirayama et al., 1999). It was concluded that Clb5p is especially active at phosphorylating Sic1p and Hct1p (Fig. 2A) and keeping Clb2p active. Thus, we conclude that, although cyclin targeting of CDK activity is unlikely to be essential, it strongly influences the biological activity of the complex. Certain activities of specific cyclin-Cdc28p complexes are simply undetectable in other complexes; other activities are facilitated by specific cyclins, even if activity can be detected with inappropriate cyclins at higher expression levels. There are sure to be truly non-cyclinspecific CDK activities, although none has yet been clearly characterized. Cyclin-dependent targeting of CDK activity How does a cyclin confer functional specificity on a CDK? Although the expression patterns of most cyclins correspond to the timing of their functions, the information reviewed above indicates that this is not the only aspect of cyclins that is important for functional specificity. Cyclin proteins may target CDK activity, either through cyclin-specific protein interactions or by influencing subcellular localization. Obviously, these two contributing factors may be linked, the subcellular localization limiting the accessibility of cyclin to a subset of proteins. Several laboratories have found that phosphorylation of some potential Cdk substrates is dependent on the identity of 1815 the cyclin. This work has been carried out primarily in higher eukaryotic cell lines, in which a limited number of CDK substrates are known. Sherr et al. have found that the LxCxE motif in cyclin D is required for interaction of the cyclinD–CDK complex with and efficient phosphorylation of Rb (Sherr, 1993). In fact, specificity exists among different types of cyclin D with respect to their ability to activate CDK2 and phosphorylate Rb (Ewen et al., 1993). Mutation of a similar sequence in cyclin E prevents phosphorylation of Rb by cyclinE–CDK2 (Kelly et al., 1998) and has interesting biological consequences. Peeper et al. found that cyclin-A–CDK2 and cyclin-A–CDC2, but not cyclin-B–CDK2 or cyclin-B–CDC2 complex can phosphorylate the Rb-like protein p107 (Peeper et al., 1993). Cyclin-A–CDK2 and cyclin-B–CDK2, but not cyclin-D–CDK2 can phosphorylate the E2F-1–DP-1 transcription factor complex. Interestingly, phosphorylation of E2F-1–DP-1 by cyclin-A–CDK2 inhibits the DNA-binding activity of the transcription complex, whereas cyclin-B–CDK2 phosphorylation does not (Dynlacht et al., 1997). CyclinA–CDK2, but not cyclin-E–CDK2, phosphorylates the 34 kDa subunit of the human single-stranded-DNA-binding protein complex (SSBP) and lamin B (Gibbs et al., 1996; Horton and Templeton, 1997). The human papillomavirus DNA replication initiation factor E1 binds to cyclin E, cyclin A, cyclin B and cyclin F, but not cyclin D1(Ma et al., 1999). Studies of T470 breast cancer cell nuclear lysates find that cyclin-D1–CDK4 phosphorylates a 24 kDa and 34 kDa protein, whereas cyclin-D3–CDK4 phosphorylates 24-kDa, 42-kDa, 102-kDa, and 105-kDa proteins. The cyclin-D3–CDK6 complex phosphorylates 102-kDa and 105-kDa proteins, but not a 24 kDa protein. These data suggest that there are substrates specific to the cyclin (the 102-kDa and 105-kDa proteins phosphorylated in the presence of cyclin D3 but not cyclin D1) and substrates specific to the CDK (the 24 kDa protein phosphorylated in the presence of CDK4, but not CDK6; Sarcevic et al., 1997). Cyclin-specific protein interactions are not limited to potential substrates. In budding yeast, specific inhibitors recognize specific cyclin-CDK complexes. As described in the previous section, the Far1p inhibitor is able to bind to and inhibit Cln-Cdc28p complexes but not Clb-Cdc28p complexes (Jeoung et al., 1998; Peter and Herskowitz, 1994). Conversely, the Sic1p and Swe1p inhibitors are able to inhibit Clb-Cdc28p complexes but not Cln-Cdc28p complexes (Schwob et al., 1994). Cks1p is required for Cln2-Cdc28p complex formation but not Clb-Cdc28p complex formation (Reynard et al., 2000). The fission yeast Rum1p protein inhibits the Cdc13p and Cig2p cyclins, but not Puc1p or Cig1p cyclin in complex with Cdc2p (Benito et al., 1998). In vitro, the higher eukaryotic CDK inhibitors p21 and p27 are able to bind cyclins directly. This binding exhibits some specificity, since p21 is able to bind to cyclin E more efficiently than to cyclin A and cyclin B, and does not bind to D-type cyclins (Chen et al., 1996). Specific inhibitors are also known to bind preferentially to different CDK components of cyclin-CDK complexes in higher eukaryotes (Morgan, 1995; Sherr and Roberts, 1999). Viral cyclin D homologs have been identified in three types of γ-herpesviridae (Cesarman et al., 1996; Nicholas et al., 1992; Virgin et al., 1997). Two have been shown to bind and activate eukaryotic CDK6 and CDK4 in higher eukaryotic cells. When bound to CDK4 and CDK6, viral cyclins are able 1816 JOURNAL OF CELL SCIENCE 114 (10) to phosphorylate substrates normally phosphorylated by cyclin-D–CDK complexes, such as Rb, yet are resistant to inhibition by the INK4 and Cip/Kip families of CDK inhibitors. The viral cyclin-CDK6 complexes also demonstrate a broader substrate range than that observed for endogenous cyclin-D–CDK6 complexes (Chang et al., 1996; Godden-Kent et al., 1997; Jung et al., 1994; Li et al., 1997b; Swanton et al., 1997). Tyrosine phosphorylation of CDK inhibits its activity, and CDK can subsequently be activated by Cdc25p-dependent dephosphorylation. In the case of cyclin-B–Cdc2p complexes, the inhibitory phosphorylation of Cdc2p occurs after complex formation, which suggests that the cyclin binding is important for this regulation (Solomon et al., 1990). Cdc25p is also better able to bind to cyclin-CDK complexes than to monomeric CDK in vitro, which suggests that the cyclin brings the CDK into contact with Cdc25p more efficiently (Morris and Divita, 1999). The relationship between CDC25 and cyclins is complex, since cyclin B, but not A- or D-type cyclins, is able to bind to CDC25A, which results in activation of the phosphatase (Galaktionov and Beach, 1991; Zheng and Ruderman, 1993). During early embryogenesis, the cyclin-A–CDC2 complex appears to be a poor substrate for the kinase that phosphorylates and inhibits CDC2, whereas cyclin-B–CDC2 is not. Additionally, cyclin-A–CDC2 complexes do not require the CDC25 tyrosine phosphatase for activation, whereas cyclinB–CDC2 complexes do (Devault et al., 1992). In these cases CDC2 is inhibited differentially depending on the identity of its cognate cyclin. A finding consistent with this is that cyclinB–CDC2, but not cyclin-A–CDC2 complexes, are regulated by tyrosine phosphorylation during meiosis in starfish oocytes (Okano-Uchida et al., 1998). Interactions between CDC25 and cyclin might occur through the highly conserved hydrophobic patch region (described below), and potential competition might exist between p21 inhibitor, substrate and CDC25 for interaction with cyclin-CDK complex through the hydrophobic patch (Adams et al., 1996; Saha et al., 1997). The hydrophobic patch region of cyclin A has been described as a docking site for substrates (Shulman et al., 1998). Mutation of this region reduces the ability of cyclin A to bind to specific substrates but does not reduce activation of CDK2 kinase activity (Shulman et al., 1998). Likewise, stable association of substrates such as p21, Rb and E2F requires specific substrate domains that, when mutated, inhibit substrate interactions (Adams et al., 1999; Adams et al., 1996). Small peptides designed to mimic substrate domains show specificity in their ability to block cyclin A activity but not cyclin B activity (Adams et al., 1996). Residues within the hydrophobic patch region of cyclin are highly conserved, and mutation of these residues in yeast Clb5p strongly impairs Clb5p function but not activity of Cdc28p towards the nonspecific substrate histone H1, which is consistent with data for cyclin A hydrophobic-patch mutants (Cross et al., 1999). The hydrophobic patch in cyclin A mediates interactions with the cyclin inhibitor p27. In twohybrid analysis, Clb5p also interacts with the higher eukaryotic cyclin inhibitor p27 through this conserved domain (Cross and Jacobson, 2000). Although no p27 homolog is thought to exist in budding yeast, these data indicate that this domain is capable of mediating cyclin-protein interactions. Confirmation of this idea requires identification of relevant Clb5p targets. Two- hybrid analysis has identified proteins that interact specifically with Clb5p but not Clb2p, and almost all of these targets also require the Clb5p hydrophobic patch to be intact (M. D. Jacobson, B. R. Drees and F.R.C., unpublished data); however, it is unclear whether any of these are authentic Clb5p interactions in vivo. The yeast mitotic cyclin Clb2p is unable to bind to p27 in the two-hybrid assay, although it retains most sequence signatures of the conserved hydrophobic patch. However, mutation of the hydrophobic patch domain does alter the functional profile of Clb2p. The hydrophobic patch mutant of Clb2p is almost negative in Clb2p-specific genetic assays, but, intriguingly, inactivation of the hydrophobic patch allows rescue in contexts normally restricted to Clb5p (Cross and Jacobson, 2000). These data suggest that the normal activity of Clb2p may require this targeting domain, and abnormal Clb2p activity towards normally Clb5p-specific events might be restricted by the targeting domain. In summary, the hydrophobic patch could be a conserved substrate recognition domain co-opted by p27 to anchor a kinase-inhibitory region (Russo et al., 1996). We speculate that differences in residues flanking the core domain could confer binding specificity. The hydrophobic patch region is important for cyclin-CDK interactions that are cyclin specific (as described above). The genetic and two-hybrid studies of Clb5p and Clb2p summarized above are consistent with this speculation but do not prove it. Thus, the ability of cyclin-CDK complexes to interact with cellular proteins is influenced by the identity of the cyclin component of the complex. In many cases, there is evidence that this can occur independently of potential differences in expression patterns or cyclin subcellular localization. Taken together, the ability of cyclin proteins to mediate specific protein interactions provides a likely mechanism for cyclindependent functional specificity of cyclin-CDK activity, although clearly defined and physiologically relevant cyclinCDK targets will need to be defined and tested for specific cyclin binding before this idea can be established. There has been significant progress along these lines in mammalian systems in the identification of specific cyclin–CDK-complexbinding proteins and substrates. Progress in the yeast field has been significantly slower on this important front. Cyclin specificity and subcellular localization An additional mechanism that contributes to the functional specificity of cyclin-CDK complexes is the control of their subcellular localization (reviewed in Pines, 1999). Differential subcellular localization of complexes could bring specific complexes into contact with potential substrates, keep complexes sequestered from improper substrates or expose the complex to activators or inhibitors that are localized to specific compartments. In this sense, control of cyclin subcellular localization is potentially linked to the control of cyclin-protein interactions. The subcellular localization patterns of many cyclins have been characterized and generally correlate well with cyclin function, such that cyclins are in the right place at the right time for their predicted functions (Baldin et al., 1993; Cardosa et al., 1993; Diehl and Sherr, 1997; Hagting et al., 1998; Hood et al., 2001; Knoblich et al., 1994; Lukas et al., 1994; Maridor Cyclin specificity: how many wheels do you need on a unicycle? et al., 1993; Ohtsubo et al., 1995; Pines and Hunter, 1991). In addition to this correlation, experimental data indicate that cyclin subcellular localization is important for cyclin function. The higher eukaryotic G1-type cyclin D1 is localized to the nucleus during G1 phase and then redistributes to the cytoplasm once DNA replication begins (Baldin et al., 1993). A mutant cyclin D1 that is unable to enter the nucleus is unable to activate DNA replication in fibroblasts (Diehl and Sherr, 1997). Higher eukaryotic cyclin B1 has a complex localization pattern, accumulating in the nucleus during mitosis just prior to nuclear envelope breakdown. The ability of cyclin B1 to promote mitosis in frog eggs is abolished in a mutant that does not localize to the nucleus (Li et al., 1997a). Interestingly, cyclin B1 that is targeted to the nucleus by addition of a nuclear localization signal (NLS) or through disruption of the cyclin B1 nuclear export signal (NES) shows a defect in DNAdamage-induced G2 arrest (Jin et al., 1998; Toyoshima et al., 1998). The cyclin-E–CDK2 complex and its substrate p220 (or NPAT) colocalize to Cajal bodies (specific subnuclear organelles associated with histone gene clusters). The timing of p220 phosphorylation correlates with the appearance of cyclin E in Cajal bodies at the beginning of G1/S boundary and appears to be important for histone transcription (Ma et al., 2000; Zhao et al., 2000). Cyclin B1 and cyclin B2 are localized to microtubules and the Golgi apparatus, respectively; this suggests that these two cyclins might have distinct functions in the cell cycle that are independent of their expression patterns and CDK partner (Draviam et al., 2001; Jackman et al., 1995). Similarly, Drosophila cyclin A and cyclin B both accumulate in the cytoplasm, whereas cyclin B3 accumulates in the nucleus (Jacobs et al., 1998). Strong evidence for an influence of subcellular localization on cyclin specificity comes from the study of G1 cyclin localization in budding yeast. The cyclins Cln2p and Cln3p support cell cycle progression through the same cell cycle step but through distinct mechanisms (see above). These two cyclins have distinct subcellular localization patterns. Cln3p is found primarily in the nucleus, which is consistent with its role as a transcriptional activator (Miller and Cross, 2000). Cln2p is found primarily in the cytoplasm, although a pool of Cln2p also localizes to the nucleus (Miller and Cross, 2000; M.E.M. and F.R.C., unpublished). Nuclear localization of Cln3p requires a C-terminal NLS (M.E.M. and F.R.C., unpublished), and deletion of this sequence results in the cytoplasmic accumulation of Cln3p. Functional analysis of a Cln3p mutant that lacks this NLS indicates that it can rescue strains that Cln2p can rescue, but that wild-type Cln3p cannot. Therefore, when Cln3p takes on a Cln2p-like subcellular localization pattern, it also takes on Cln2p-like functions. This is due to the shift in localization patterns and not to other defects associated with the Cln3p mutant, because addition of a heterologous NLS moves the mutant Cln3p back into the nucleus and abolishes Cln2p-like functions. These data (Miller and Cross, 2000; M.E.M. and F.R.C., unpublished) indicate that the subcellular localizations of the G1 cyclins Cln2p and Cln3p contribute to their functional specificity. The higher eukaryotic cyclins B1 and B2 also exemplify the importance of subcellular localization. When cytoplasmic, cyclin B1 is partially localized to microtubules and is capable of reorganizing nuclear, cytoskeletal and membrane compartments; whereas cyclin B2 is localized to the Golgi 1817 apparatus and is able to disassemble it. Using chimeric proteins, Draviam et al. replaced the N-terminus of cyclin B2 with the N-terminus of cyclin B1 and found that this chimera was redirected to the Golgi (Draviam et al., 2001). The reciprocal chimera, in which the N-terminus of cyclin B1 was replaced with the N-terminus of cyclin B2, was liberated from the Golgi. Directing cyclin B1 to the Golgi in this way restricted its function to re-organization of the Golgi apparatus, whereas liberation of cyclin B2 allowed it to re-organize the cytoskeleton, taking on cyclin B1-like function. The CDKbinding region and potential substrate-binding hydrophobic patch domain was not switched in these chimeras. In this case, it appears that localization, and not substrate targeting through the hydrophobic patch, influenced the activity of these B-type cyclins (Draviam et al., 2001). Concluding remarks In summary, cyclins can influence when and where CDK is active, and therefore may be more than a conformational on/off switch for CDK activity. This cyclin-dependent targeting can occur through temporal regulation of cyclin expression and spatial regulation of cyclin localization. Additionally, cyclins influence CDK activity by mediating critical interactions between cyclin-CDK complexes and cellular proteins (including substrates, inhibitors and activators). Targeting is likely to occur through a combination of factors discussed here, which include temporal expression, protein associations, subcellular localization and possibly additional mechanisms not yet elucidated. Regulated oscillations of CDK activity required for the minimal cell cycle can probably be achieved through control of the level of a single cyclin protein, and this is arguably the condition under which the eukaryotic cell cycle initially evolved (Nasmyth, 1995; Nasmyth, 1996). The information reviewed above suggests that the situation in most modern eukaryotes may be more complex and that significant enhancement of biological efficiency of cyclin-CDK activity occurs through specific interaction of different cyclins with regulators and targets. References Adams, P. D., Sellers, W. R., Sharma, S. K., Wu, A. D., Nalin, C. M. and Kaelin, W. G., Jr (1996). Identification of a cyclin-cdk2 recognition motif present in substrates and p21-like cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 6623-6633. Adams, P. D., Li, X., Sellers, W. R., Baker, K. B., Leng, X., Harper, J. W., Taya, Y. and Kaelin, W. G., Jr (1999). Retinoblastoma Protein Contains a C-terminal Motif that Targets it for Phosphorylation by Cyclin-Cdk complexes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 1068-1080. Althoefer, H., Schleiffer, A., Wassmann, K., Nordheim, A. and Ammerer, G. (1995). Mcm1 is required to coordinate G2-specific transcription in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15, 5917-5928. Amon, A. (1997). Regulation of B-type cyclin proteolysis by Cdc28associated kinases in budding yeast. EMBO J. 16, 2693-2702. Amon, A., Tyers, M., Futcher, B. and Nasmyth, K. (1993). Mechanisms that help the yeast cell cycle clock tick: G2 cyclins transcriptionally activate G2 cyclins and repress G1 cyclins. Cell 74, 993-1007. Bai, C., Sen, P., Hofmann, K., Ma, L., Goebl, M., Harper, J. W. and Elledge, S. J. (1996). SKP1 connects cell cycle regulators to the ubiquitin proteolysis machinery through a novel motif, the F-box. Cell 86, 263-274. Baldin, V., Lukas, J., Marcote, M. J., Pagano, M. and Draetta, G. (1993). Cyclin D1 is a nuclear protein required for cell cycle progression in G1. Genes Dev. 7, 812-821. Benito, J., Martin-Castellanos, C. and Moreno, S. (1998). Regulation of the 1818 JOURNAL OF CELL SCIENCE 114 (10) G1 phase of the cell cycle by periodic stabilization and degradation of the p25rum1 CDK inhibitor. EMBO J. 17, 482-497. Benton, B. K., Tinkelenberg, A. H., Jean, D., Plump, S. D. and Cross, F. R. (1993). Genetic analysis of Cln/Cdc28 regulation of cell morphogenesis in budding yeast. EMBO J. 12, 5267-5275. Booher, R. N., Deshaies, R. J. and Kirschner, M. W. (1993). Properties of Saccharomyces cerevisiae wee1 and its differential regulation of p34CDC28 in response to G1 and G2 cyclins. EMBO J. 12, 3417-3426. Breeden, L. (1996). Start-specific transcription in yeast. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 208, 95-127. Cardosa, M. C., Leonhardt, H. and Nada-Ginard, B. (1993). Reversal of terminal differentiation and control of DNA replication cyclin A and Cdk2 specifically localize at subnuclear sites of DNA replication. Cell 74, 979992. Cesarman, E., Nador, R. G., Bai, F., Bohenzky, R. A., Russo, J. J., Moore, P. S., Chang, Y. and Knowles, D. M. (1996). Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus contains G protein-coupled receptor and cyclin D homologs which are expressed in Kaposi’s sarcoma and malignant lymphoma. J. Virol. 70, 8218-8223. Chang, Y., Moore, P. S., Talbot, S. J., Boshoff, C. H., Zarkowska, T., Godden-Kent, D., Paterson, H., Weiss, R. A. and Mittnacht., S. (1996). Cyclin encoded by KS herpesvirus. Nature 382, 410. Chen, J., Saha, P., Kornbluth, S., Dynlacht, B. D. and Dutta, A. (1996). Cyclin-binding motifs are essential for the function of p21CIP1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 4673-4682. Cross, F. R. (1995). Starting the cell cycle: what’s the point? Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 7, 790-797. Cross, F. R. and Jacobson, M. D. (2000). Conservation and function of a potential substrate-binding domain in the yeast Clb5 B-type cyclin. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 4782-4790. Cross, F. R., Yuste-Rojas, M., Gray, S. and Jacobson, M. D. (1999). Specialization and targeting of B-type cyclins. Mol. Cell 4, 11-19. Cvrcková, F. and Nasmyth, K. (1993). Yeast G1 cyclins CLN1 and CLN2 and a GAP-like protein have a role in bud formation. EMBO J. 12, 5277-5286. De Bondt, H. L., Rosenblatt, J., Jancarik, J., Jones, H. D., Morgan, D. O. and Kim, S.-H. (1993). Crystal structure of cyclin-dependent kinase 2. Nature 363, 595-602. Deshaies, R. J. (1997). Phosphorylation and proteolysis: partners in the regulation of cell division in budding yeast. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 7, 716. Devault, A., Fesquet, D., Cavadore, J.-C., Garrigues, A.-M., Labbé, J.-C., Lorca, T., Picard, A., Philippe, M. and Dorée, M. (1992). Cyclin A potentiates maturation-promoting factor activation in the early Xenopus embryo via inhibition of the tyrosine kinase that phosphorylates CDC2. J.Cell Biol. 118, 1109-1120. Di Como, C. J., Chang, H. and Arndt, K. T. (1995). Activation of CLN1 and CLN2 G1 cyclin gene expression by BCK2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15, 1835-1846. Diehl, J. A. and Sherr, C. J. (1997). A dominant-negative cyclin D1 mutant prevents nuclear import of cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (CDK4) and its phosphorylation by CDK-activating kinase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 7362-7374. Dirick, L. and Nasmyth, K. (1991). Positive feedback in the activation of G1 cyclins in yeast. Nature 351, 754-757. Dirick, L., Böhm, T. and Nasmyth, K. (1995). Roles and regulation of ClnCdc28 kinases at the start of the cell cycle of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 14, 4803-4813. Donaldson, A. D., Raghuraman, M. K., Friedman, K. L., Cross, F. R., Brewer, B. J. and Fangman, W. L. (1998). CLB5-dependent activation of late replication origins in S. cerevisiae. Mol. Cell 2, 173-182. Draviam, V. M., Orrechia, S., Lowe, M., Pardi, R. and Pines, J. (2001). The localization of human Cyclins B1 and B2 determines their substrate specificity and neither enzyme requires MEK to disassemble the Golgi apparatus. J. Cell Biol. 152, 1-15. Dynlacht, B. D., Moberg, K., Lees, J. A., Harlow, E. and Zhu, L. (1997). Specific regulation of E2F family members by cyclin-dependent kinases. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 3867-3875. Epstein, C. B. and Cross, F. R. (1992). CLB5: a novel B cyclin from budding yeast with a role in S phase. Genes Dev. 6, 1695-1706. Epstein, C. B. and Cross, F. R. (1994). Genes that can bypass the CLN requirement for Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell cycle START. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14, 2041-2047. Ewen, M. E., Sluss, H. K., Sherr, C. J., Matsushime, H., Kato, J. and Livingston, D. M. (1993). Functional interactions of the retinoblastoma protein with mammalian D-type cyclins. Cell 73, 487-497. Fisher, D. L. and Nurse, P. (1996). A single fission yeast mitotic cyclin B p34CDC2 kinase promotes both S-phase and mitosis in the absence of G1 cyclins. EMBO J. 15, 850-860. Galaktionov, K. and Beach, D. (1991). Specific activation of cdc25 tyrosine phosphatases by B- type cyclins: evidence for multiple roles of mitotic cyclins. Cell 67, 1181-1194. Gartner, A., Jovanovic, A., Jeoung, D.-I., Bourlat, S., Cross, F. R. and Ammerer, G. (1998). Pheromone-dependent G1 cell cycle arrest requires Far1 phosphorylation, but may not involve inhibition of Cdc28-Cln2 kinase, in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 3681-3691. Geng, Y., Whoriskey, W., Park, M. Y., Bronson, R. T., Medema, R. H., Li, T., Weinberg, R. A. and Sicinski, P. (1999). Rescue of cyclin D1 deficiency by knockin cyclin E. Cell 97, 767-777. Ghiara, J. B., Richardson, H. E., Sugimoto, K., Henze, M., Lew, D. J., Wittenberg, C. and Reed, S. I. (1991). A cyclin B homolog in S. cerevisiae: chronic activation of the Cdc28 protein kinase by cyclin prevents exit from mitosis. Cell 65, 163-174. Gibbs, E., Pan, Z.-Q., Niu, H. and Hurwitz, J. (1996). Studies on the in vitro phosphorylation of HSSB-p34 and p107 by cyclin-dependent kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 22847-22854. Godden-Kent, D., Talbot, S. J., Boshoff, C., Chang, Y., Moore, P., Weiss, R. A. and Mittnacht, S. (1997). The cyclin encoded by Kaposi’s sarcomaassociated herpesvirus stimulates cdk6 to phosphorylate the retinoblastoma protein and histone H1. J. Virol. 71, 4193-4198. Haase, S. B. and Reed, S. I. (1999). Evidence that a free-running oscillator drives G1 events in the budding yeast cell cycle. Nature 401, 394-397. Haase, S. B., Winey, M. and Reed, S. I. (2001). Multi-step control of spindle pole body duplication by cyclin-dependent kinase. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 38-42. Hagting, A., Karlsson, C., Clute, P., Jackman, M. and Pines, J. (1998). MPF localization is controlled by nuclear export. EMBO J. 17, 4127-4138. Hayles, J., Fisher, D., Woollard, A. and Nurse, P. (1994). Temporal order of S phase and mitosis in fission yeast is determined by the state of the p34cdc2mitotic B cyclin complex. Cell 78, 813-822. Hood, J. K., Hwang, W. W. and Silver, P. A. (2001). The Saccharomyces cerevisiae cyclin Clb2p is targeted to multiple subcellular locations by cisand trans-acting determinants. J. Cell Sci. 114, 589-597. Horton, L. E. and Templeton, D. J. (1997). The cyclin box and C-terminus of cyclins A and E specify CDK activation and substrate specificity. Oncogene 14, 491-498. Irniger, S., Simonetta, P., Michaelis, C. and Nasmyth, K. (1995). Genes involved in sister chromatid separation are needed for B-type cyclin proteolysis in budding yeast. Cell 81, 269-277. Jackman, M., Firth, M. and Pines, J. (1995). Human cyclins B1 and B2 are localized to strikingly different structures: B1 to microtubules, B2 primarily to the Golgi apparatus. EMBO J. 14, 1646-1654. Jacobs, H. W., Knoblich, J. A. and Lehner, C. F. (1998). Drosophila Cyclin B3 is required for female fertility and is dispensable for mitosis like cyclin B. Genes Dev. 12, 3741-3751. Jacobson, M. D., Gray, S., Yuste-Rojas, M. and Cross, F. R. (2000). Testing cyclin specificity in the exit from mitosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 4483-4493. Jeffrey, P. D., Russo, A. A., Polyak, K., Gibbs, E., Hurwitz, J., Massague, J. and Pavletich, N. (1995). Mechanism of CDK activation revealed by the structure of a cyclinA-CDK2 complex. Nature 376, 313-320. Jeoung, D., Oehlen, L. J. W. M. and Cross, F. R. (1998). Cln3-associated kinase activity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is regulated by the mating factor pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 433-441. Jin, P., Hardy, S. and Morgan, D. O. (1998). Nuclear localization of cyclin B1 controls mitotic entry after DNA damage. J. Cell Biol. 18, 875-885. Jung, J. U., Stager, M. and Desrosiers, R. C. (1994). Virus-encoded cyclin. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1, 7235-7244. Kato, J.-Y. and Sherr, C. J. (1993). Inhibition of granulocyte differentiation by G1 cyclins D2 and D3 but not D1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90, 1151311517. Kelly, B., Wolfe, K. G. and Roberts, J. M. (1998). Identification of a substrate-targeting domain in cyclin E necessary for phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 2535-2540. King, R. W., Deshaies, R. J., Peters, J. M. and Kirschner, M. W. (1996). How proteolysis drives the cell cycle. Science 274, 1652-1659. Knoblich, J. A., Sauer, K., Jones, L., Richardson, H., Saint, R. and Lehner, C. F. (1994). Cyclin E controls S phase progression and its down regulation during Drosophila embryogenesis is required for the arrest of cell proliferation. Cell 77, 107-120. Koch, C. and Nasmyth, K. (1994). Cell cycle regulated transcription in yeast. Curr. Opin.Cell Biol. 6, 451-459. Koranda, M., Schleiffer, A., Endler, L. and Ammerer, G. (2000). Forkhead- Cyclin specificity: how many wheels do you need on a unicycle? like transcription factors recruit Ndd1 to the chromatin of G2/M-specific promoters. Nature 406, 94-98. Kumar, R., Reynolds, D. M., Shevchenko, A., Shevchenko, A., Goldstone, S. D. and Dalton, S. (2000). Forkhead transcription factors, Fkh1p and Fkh2p, collaborate with Mcm1p to control transcription required for Mphase. Curr. Biol. 10, 896-906. Levine, K. and Cross, F. R. (1995). Structuring cell-cycle biology. Structure 3, 1131-1134. Levine, K., Huang, K. and Cross, F. R. (1996). Saccharomyces cerevisiae G1 cyclins differ in their intrinsic functional specificities. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 6794-6803. Levine, K., Kiang, L., Jacobson, M. D., Fisher, R. P. and Cross, F. R. (1999). Directed evolution to bypass cyclin requirements for the Cdc28p cyclin-dependent kinase. Mol. Cell 4, 353-363. Lew, D. J. and Reed, S. I. (1993). Morphogenesis in the yeast cell cycle: regulation by Cdc28 and cyclins. J.Cell Biol. 120, 1305-1320. Li, J., Meyer, A. N. and Donoghue, D. (1997a). Nuclear localization of cyclin B1 mediates ints biological activity and is regulated by phosphorylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 502-507. Li, M., Lee, H., Yoon, D. W., Albrecht, J. C., Fleckenstein, B., Neipel, F. and Jung, J. U. (1997b). Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus encodes a functional cyclin. J. Virol. 71, 1984-1991. Li, X. and Cai, M. (1999). Recovery of the yeast cell cycle from heat shockinduced G(1) arrest involves a positive regulation of G(1) cyclin expression by the S phase cyclin Clb5. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 24220-242231. Lukas, J., Pagano, M., Staskova, Z., Draetta, G. and Bartek, J. (1994). Cyclin D1 protein oscillates and is essential for cell cycle progression in human tumour cell lines. Oncogene 9, 707-718. Ma, T., Zou, N., Lin, B. Y., Chow, L. T. and Harper, J. W. (1999). Interaction between cyclin-dependent kinases and human papillomavirus replicationinitiation protein E1 is required for efficient viral replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 382-387. Ma, T., Tine, B. A. V., Wei, Y., Garrett, M. D., Nelson, D., Adams, P. D., Wang, J., Qin, J., Chow, L. T. and Harper, J. W. (2000). Cell cycleregulated phosphorylation of p220 NPAT by cyclin E/Cdk2 in Cajal bodies promotes histone gene transcription. Genes Dev. 14, 2298-2313. Maridor, G., Gallant, P., Golsteyn, R. and Nigg, E. A. (1993). Nuclear localization of vertebrate cyclin A correlates with its ability to form complexes with cdk catalytic subunits. J. Cell Sci. 106, 535-544. Martin-Castellanos, C., Blanco, M. A., Prada, J. M. D. and Moreno, S. (2000). The puc1 cyclin regulates the G1 phase of the fission yeast cell cycle in response to cell size. Mol. Biol. Cell 11, 543-554. McInerny, C. J., Partridge, J. F., Mikesell, G. E., Creemer, D. P. and Breeden, L. L. (1997). A novel Mcm1-dependent element in the SWI4, CLN3, CDC6, and CDC47 promoters activates M/G1-specific transcription. Genes Dev. 11, 1277-1288. Miller, M. E. and Cross, F. R. (2000). Distinct subcellular localization patterns contribute to functional specificity of the Cln2 and Cln3 cyclins of S. cerevisaie. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 542-55. Morgan, D. O. (1995). Principles of CDK Regulation. Nature 374, 131-134. Morris, M. C. and Divita, G. (1999). Characterization of the interactions between human cdc25C, cdks, cyclins, and cdk-cyclin complexes. J. Mol. Biol. 286, 475-487. Nasmyth, K. (1993). Control of the yeast cell cycle by the Cdc28 protein kinase. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 5, 166-179. Nasmyth, K. (1995). Evolution of the cell cycle. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 349, 271-281. Nasmyth, K. (1996). At the heart of the budding yeast cell cycle. Trends Genet. 12, 405-412. Nicholas, J., Cameron, K. R. and Honess, R. W. (1992). Herpesvirus saimiri encodes homologues of G protein-coupled receptors and cyclins. Nature 355, 362-365. Oehlen, L. J. W. M. and Cross, F. R. (1994). G1 cyclins CLN1 and CLN2 repress the mating factor response pathway at Start in the yeast cell cycle. Genes Dev. 8, 1058-1070. Ohtsubo, M., Theodoras, A. M., Schumacher, J., Roberts, J. M. and Pagano, M. (1995). Human cyclin E, a nuclear protein essential for the G1to-S phase transition. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15, 2612-2524. Okano-Uchida, T., Sekiae, T., Lee, K., Okumura, E., Tachibana, K. and Kishimoto, T. (1998). In vivo regulation of cyclin A/Cdc2 and cyclin B/Cdc2 through meiotic and early cleavage cycles in starfish. Dev. Biol. 197, 39-53. Peeper, D. S., Parker, L. L., Ewen, M. E., Toebes, M., Hall, F. L., Xu, M., Zantema, A., Van der Eb, A. J. and Piwnica-Worms, H. (1993). A- and 1819 B-type cyclins differentially modulate substrate specificity of cyclin-cdk complexes. EMBO J. 12, 1947-1954. Peter, M. and Herskowitz, I. (1994). Direct inhibition of the yeast cyclindependent kinase Cdc28-Cln by Far1. Science 265, 1228-1231. Pic, A., Lim, F. L., Ross, S. J., Veal, E. A., Johnson, A. L., Sultan, M. R., West, A. G., Johnston, L. H., Sharrocks, A. D. and Morgan, B. A. (2000). The forkhead protein Fkh2 is a component of the yeast cell cycle transcription factor SFF. EMBO J. 19, 3750-3761. Pines, J. (1999). Four-dimensional control of the cell cycle. Nature Cell Biology 1, E73-79. Pines, J. and Hunter, T. (1991). Human cyclins A and B1 are differentially located in the cell and undergo cell cycle-dependent nuclear transport. J. Cell Biol. 115, 1-17. Rao, P. N. and Johnson, R. N. (1970). Mammalian cell fusion: studies on the regulation of DNA synthesis and mitosis. Nature 225, 159-164. Reynard, G. J., Reynolds, W., Verma, R. and Deshaies, R. J. (2000). Cks1 is required for G1 cyclin-cyclin−dependent kinase activity in budding yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 5858-5864. Rudner, A. D., Hardwick, K. G. and Murray, A. W. (2000). Cdc28 activates exit from mitosis in budding yeast. J. Cell Biol. 149, 1361-1376. Rudner, A. D. and Murray, A. W. (2000). Phosphorylation by Cdc28 activates the Cdc20-dependent activity of the anaphase-promoting complex. J. Cell Biol. 149, 1377-1390. Russo, A. A., Jeffrey, P. D., Patten, A. K., Massagué, J. and Pavletich, N. P. (1996). Crystal structure of the p27Kip1 cyclin-dependent-kinase inhibitor bounds to the cyclin A-Cdk2 complex. Nature 382, 335-331. Saha, P., Eichbaum, Q., Silberman, W. D., Mayer, B. J. and Dutta, A. (1997). p21CIP1 and Cdc25A: competition between an inhibitor and an activator of Cyclin-Dependent Kinase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 4338-4345. Sanchez-Diaz, A., Gonzalez, I., Arellano, M. and Moreno, S. (1998). The Cdk inhibitors p25rum1 and p40SIC1 are functional homologues that play similar roles in the regulation of the cell cycle in fission and budding yeast. J. Cell Sci. 111, 843-851. Sarcevic, B., Lilischkis, R. and Sutherland, R. (1997). Differential phosphorylation of T-47D human breast cancer cell substrates by D1-, D3-, E-, and A-type Cyclin-CDK complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 3332733337. Schwab, M., Lutum, A. S. and Seufert, W. (1997). Yeast Hct1 is a regulator of Clb2 cyclin proteolysis. Cell 90, 683-693. Schwob, E. and Nasmyth, K. (1993). CLB5 and CLB6, a new pair of B cyclins involved in DNA replication in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 7, 1160-1175. Schwob, E., Böhm, T., Mendenhall, M. D. and Nasmyth, K. (1994). The Btype cyclin kinase inhibitor p40SIC1 controls the G1 to S transition in S. cerevisiae. Cell 79, 233-244. Segal, M., Clarke, D. J. and Reed, S. I. (1998). Clb5-associated kinase activity is required early in the spindle pathway for correct preanaphase nuclear positioning in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 143, 135-145. Sherr, C. J. (1993). Mammalian G1 cyclins. Cell 73, 1059-1065. Sherr, C. J. and Roberts, J. M. (1999). CDK inhibitors: positive and negative regulators of G1-phase progression. Genes Dev. 13, 1501-1512. Shirayama, M., Toth, A., Galova, M. and Nasmyth, K. (1999). APCCdc20 promotes exit from mitosis by destroying the anaphase inhibitor Pds1 and cyclin Clb5. Nature 402, 203-207. Shulman, B. A., Llindstrom, D. L. and Harlow, E. (1998). Substrate recruitment to cyclin-dependent kinase 2 by a multipurpose docking site on cyclin A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 10453-10458. Solomon, M. J., Glotzer, M., Lee, T. H., Philippe, M. and Kirschner, M. W. (1990). Cyclin activation of p34cdc2. Cell 63, 1013-1024. Stern, B. and Nurse, P. (1996). A quantitative model for the cdc2 control of S phase and mitosis in fission yeast. Trends Genet. 12, 345-350. Stillman, B. (1996). Cell cycle control of DNA replication. Science 274, 16591664. Stuart, D. and Wittenberg, C. (1995). CLN3, not positive feedback, determines the timing of CLN2 transcription in cycling cells. Genes Dev. 9, 2780-2794. Stuart, D. and Wittenberg, C. (1998). CLB5 and CLB6 are required for premeiotic DNA replication and activation of the meiotic S/M checkpoint. Genes Dev. 12, 2698-2710. Surana, U., Amon, A., Dowzer, C., McGrew, J., Byers, B. and Nasmyth, K. (1993). Destruction of the CDC28/CLB mitotic kinase is not required for the metaphase to anaphase transition in budding yeast. EMBO J. 12, 1969-1978. Swanton, C., Mann, D. J., Fleckenstein, B., Neipel, F., Peters, G. and Jones, 1820 JOURNAL OF CELL SCIENCE 114 (10) N. (1997). Herpes viral cyclin/Cdk6 complexes evade inhibition by CDK inhibitor proteins. Nature 13, 184-187. Toyoshima, F., Moriguchi, T., Wada, A., Fukuda, M. and Nishida, E. (1998). Nuclear export of cyclin B1 and its possible role in the DNA damage-induced G2 checkpoint. EMBO J. 17, 2728-2735. Tyers, M., Tokiwa, G. and Futcher, B. (1993). Comparison of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae G1 cyclins: Cln3 may be an upstream activator of Cln1, Cln2 and other cyclins. EMBO J. 12, 1955-1968. Valdivieso, M. H., Sugimoto, K., Jahng, K.-Y., Fernandes, P. M. B. and Wittenberg, C. (1993). FAR1 is required for posttranscriptional regulation of CLN2 gene expression in response to mating pheromone. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13, 1013-1022. Virgin, H. W., Latreille, P., Wamsley, P., Hallsworth, K., Weck, K. E., Canto, A. J. D. and Speck, S. H. (1997). Complete sequence and genomic analysis of murine gammaherpesvirus 68. J. Virol. 71, 5894-5904. Visintin, R., Craig, K., Hwang, E. S., Prinz, S., Tyers, M. and Amon, A. (1998). The phosphatase Cdc14 triggers mitotic exit by reversal of Cdkdependent phosphorylation. Molec. Cell 2, 709-718. Willems, A. R., Lanker, S., Patton, E. E., Craig, K. L., Nason, T. F., Mathias, N., Kobayashi, R., Wittenberg, C. and Tyers, M. (1996). Cdc53 targets phosphorylated G1 cyclins for degradation by the ubiquitin proteolytic pathway. Cell 86, 453-463. Zachariae, W. and Nasmyth, K. (1999). Whose end is destruction: cell division and the anaphase-promoting complex. Genes Dev. 13, 2039-58. Zachariae, W., Shin, T. H., Galova, M., Obermaier, B. and Nasmyth, K. (1996). Identification of subunits of the anaphase-promoting complex of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science 274, 1201-1204. Zachariae, W., Schwab, M., Nasmyth, K. and Seufert, W. (1998). Control of cyclin ubiquitination by CDK-regulated binding of Hct1 to the anaphase promoting complex. Science 282, 1721-1724. Zhao, J., Kennedy, B. K., Lawrence, B. D., Barbie, D. A., Matera, A. G., Fletcher, J. A. and Harlow, E. (2000). NPAT links cyclin E-Cdk2 to the regulation of replication-dependent histone gene transcription. Genes Dev. 14, 2283-2297. Zheng, X. F. and Ruderman, J. V. (1993). Functional analysis of the P box, a domain in cyclin B required for the activation of Cdc25. Cell 75, 155164. Zhu, G., Spellman, P. T., Volpe, T., Brown, P. O., Botstein, D., Davis, T. N. and Futcher, B. (2000). Two yeast forkhead genes regulate the cell cycle and pseudohyphal growth. Nature 406, 90-94.