Evaluation of Facilities Design and Methods of Handling Bison BY

advertisement

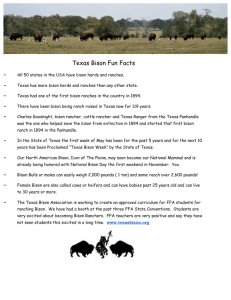

EvaluationofFacilitiesDesignandMethodsofHandlingBison BY DuaneJ.Lammers Athesissubmittedinpartialfulfillmentoftherequirementsforthe MastersofScience MajorinWildlifeandFisheriesScience SouthDakotaStateUniversity 2011 i iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my advisor Jonathan Jenks for his guidance and review of my research. John and Polly Preston for allowing me to analyze working of their bison herd. Claude and Annette Smith for the loading portion of this research and being willing to try new approaches to this process. Sam Hurst and Denise DuBroy for trying the short fences and herding of bison on two different ranches to determine the differences in capturing bison for fall roundups. Triple Seven Ranch for the 25 years I operated the ranch in a joint venture and things I tried to improve the handling of bison. And Custer State Park for their time and willingness to always explore better ways to handle their bison herd. iv Abstract Evaluation of Facilities Design and Methods for Handling Bison Duane J. Lammers 2011 There are 14 known large mammals that have been domesticated for thousands of years (Diamond:1999, 168-169). Bison (Bison bison) are not on that list even though they have been held on private ranches and in parks for over 100 years. Bison have been treated as wild, difficult to handle animals in roundups and when processing them through corrals. This project involved several research trials during different phases of capture, working bison in corrals, loading them into trucks, and when entering animals into squeeze chutes. Seventy one percent of the bison entered the squeeze chute calmly with a window design crash gate whereas 10 percent entered calmly with a solid crash gate design. When bison were herded into and through corrals and gates without capture or threat of harm, roundups and loading of bison into trucks were carried out with minimal stress on the animals. Allowing bison to be herded through the corrals, a man-made corridor, during normal pasture rotations can make roundups a one-person operation. Using different designs to work animals through corrals and into ready chutes and squeeze chutes had dramatic effects on how well animals entered. Bison can be handled in a low-stress manner for both herders and the bison. Corral designs that allow easy movement through v them can provide the conditioning results to lower stress on bison, and functionally speed the processing of animals through corrals and chutes. vi TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements…………………………..………………………………………..….i Acceptance Page ………………………………………………………………….…..….ii Abstract………………………………………………………………….…………...…..iii List of Figures……………………………………..………………….…….….…..…..viii List of Tables…..…………………………………………………………...….……..….ix Chapter 1 Justification……………………………………………………………………1 Chapter 2 Bison Roundups….…………………………………………………..…….….5 Introduction…………...………………………………………..…………..…..5 Study Area and Methods………………………………………….….……..….6 Results Lame Johnny Creek Ranch………………..…………….………..……8 Results Cheyenne River Ranch………………………….……………..…..….11 Results and Discussion…..…………………………………………….…...…13 Chapter 3 Entering Ready Chutes…………………………….…………………....……15 Introduction……………………………………………….……………….….15 Methods………………………….…………………………….………..….…15 Results and Discussion…………………………….……………………….….20 Chapter 4 Training Bison to Load…………………………………………….…..….….22 Introduction………………………………………………………….….....…..22 Methods……………………………………………………………………..…22 Results and Discussion………………………………………….……...…..…24 vii Chapter 5 Bison Crash Gate Test…………………………………………...…..………..27 Introduction……………………………………………………………..….……27 Methods……………..………………………………….…………………….....28 Results and Discussion………………………..……………………….…..……30 Conclusions and Discussion……………….…………………………….….……..….…32 Definitions and Equipment Descriptions..………………………..…….….……..….34-38 Literature Cited…………………………………………………………………....……..39 viii LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1. Hurst Ranch, Lame Johnny Corrals before Modification………………...…….7 Figure2. Lame Johnny Corrals after fence addition………………………………....……9 Figure 3. Hurst Ranch, Cheyenne River corrals roundup strategies………………..…...10 Figure 4. Cheyenne River corrals after fence addition………………….……………….12 Figure 5. 777 Ranch corral with ready chutes…………………………………….…….18 Figure 6a. Preston Ranch corral drawing with gates open……………………………….19 Figure 6b. Preston Ranch corral drawing with gates closed……………………………..19 Figure 8. Smith Ranch working and loading chute area…………………………...…….23 Figure 9. Smith Ranch working corrals with gates open………………………….…….25 Figure 10. Front view of crash gate chute……………………………………………….29 Figure 11. Side view of crash gate and chute……………………………………..……..29 ix LIST OF TABLES Table 1. Results of bison entering ready chutes………………………………….……..20 Table 2. Results of change to loading before and after training…………………….…..25 Table 3. Levels of acceptance and resistance to entering squeeze chute………………..31 1 CHAPTER 1 JUSTIFICATION Until approximately 1976, the number of bison (Bison bison) in the United States (US) and Canada numbered under 100,000 animals. Since that time, the number of bison has increased to approximately 400,000 animals about one quarter of the animals located in Canada (Firmage-O’Brien 2008) and 38,400 of those bison in the US located in South Dakota (SD). South Dakota is the number one producer of bison, the second ranked state is Nebraska with 17,900 ( National Bison Association 2010). The US has 4,449 private bison producers (USDA Agriculture Census 2007). Prior to 1976, the number of private ranches with bison were few, and parks seemed to set the standard for handling this native ungulate; Custer State Park (CSP) in South Dakota being the most prominent of those. The CSP Roundup is attended by over 10,000 people annually and viewed by millions via TV news and documentaries. During the roundup, over 50 horseback riders and a nearly equal number of people in pickup trucks and sport utility vehicles (SUV’s) round up the bison herd of 1,500 animals at a run, forcing the herd into the corral. While the CSP roundup is meant to be a tourist attraction, most believe that these methods are necessary to roundup bison. This prevailing thought is demonstrated in statements made by those perceived to be experts in the area of handling bison. Statements such as: “Handling bison is a precarious chore at best”(B. Sowell, Ph.D, TNC, personal 2 communication, 1998); “Bison are wild animals, they can be unpredictable and their tolerance for handling is less than domestic livestock” (Bison Breeders Handbook 2001). These comments are echoed by the many bison producers from around the US and Canada. Many bison owners have great difficulty in rounding up their herds and experience significant injury, mortality, and stress to animals in processing the animals through their facilities. These facilities, often very expensive fortress type operations, rival many park operations. Most parks and private ranches have relied on the technology of fences, aircraft, and SUV’s for roundups. Dan Hawkins, a long time helicopter pilot who has conducted bison roundups in Yellowstone, Wind Cave, and Badlands National Parks, has talked of how bison have become increasing hard to herd even with helicopters. Early on the animals were quite responsive to herding but some animals have become resistant to the extent where even putting the helicopter skid on their back cannot keep them from breaking away from the group during the “roundup push”. There are plans by Non-Government Organizations (NGO’s) to create some large-scale bison ranges (Dan O’Brien 2009, wildlife biologist personal communication). Some of these could easily have herds exceeding 10,000 animals. Discussions of these large-scale natural areas have not included animal handling protocols that would aid owners if a herd fails to respond to current herding methods. 3 A news crew, who happened to film the CSP roundup, watched as we completed a roundup of greater than 2,000 bison with three wranglers that resulted in the herd calmly walking into the corral the day following the CSP roundup that the discrepancy in handling bison became apparent. The genetic make up of the herd, was predominately, CSP stock with additional animals from National Bison Range, Wind Cave National Park, Badlands National Park, and Theodore Roosevelt National Park, all with similar management of bison to CSP. Therefore, one would not tend to think of those bison as any more domestic than the aforementioned herds. I have also encountered biologists at national parks that have discounted my handling methods because they assumed that their animals were wild and thus, behaved differently from those bison residing on private ranches; even though the bison on private ranches likely had similar genetics. Subsequent informal interviews with current and prospective bison ranch operations along with an unpublished survey, conducted by University of Wyoming staff and students (from personal copy received in 1989) indicated handling and facilities design were the most important issues for bison ranchers. It was concern for low-stress handling to improve the safety and cost benefits to the bison operations, and the growing concern for humane handling of animals that initiated the desire to document anecdotal stories that improved handling of bison as well as the lack of information on this subject that precipitated the following studies. It may be time to shift from improving technology associated with bison operations to just watching and walking with the bison if we are to understand behavioral responses that best accomplish future management strategies. 4 The primary objective of this research was to identify key methods of handling bison in a low-stress manner during roundups and corral work. Other objectives were to evaluate anecdotal methods using statistical analyses and provide some background to future bison managers when they develop corrals and train personnel. 5 CHAPTER 2 BISON ROUNDUPS INTRODUCTION Over the years, parks and bison ranchers have used various methods of gathering or capturing their herds. Baiting and trapping methods are often used (Corner and Connell 1958, Keiter 1997). For example, utilizing feed and/or water as an enticement to bison to enter and stay in the corral until the gate is closed is one bait method. The other most often-used roundup method involves the use of pickup trucks, all terrain vehicles (ATV’s), and/or horses to chase the animals into the corral. This event usually involves a system involving smaller pastures and/or wing fences with increasing, aggressive chasing of the animals to force them into a continuously narrowing corral system (B. Williams,Stockmanship Course 1991). These aggressive methods of roundup usually result in most or all of the animals being captured, but also can include; more man hours, damaged fences, escaped animals, injured animals, damaged equipment, occasional human injury, and very stressed bison. In contrast, prior training of bison by moving the herd through the corral two or more times per year without working them in chutes could facility roundups and decrease animal stress. Thus, the purpose of this study was to identify low-stress roundup and handling methods that work in a consistent and timely manner, regardless of goals, and to seek out facility designs that fit well with bison behavior. 6 STUDY AREA and METHODS At each of two bison ranches, traditional roundup methods were used for two years, followed by incorporating roundups in the normal grazing management system on ranches with the addition of short length of fence directing pasture changes with movement through corrals as part of the grazing rotation. The Hurst Ranch, located on Lame Johnny Creek in Custer County, South Dakota, was located about 1.6 km (1 mile) from the CSP Corrals. The Hurst Ranch started raising bison in fall of 1993. They built a pasture fence for their grazing program and corrals for their annual roundup to sort bison for sale and vaccinate the herd. The ranch consisted of 260 hectares (640 acres) of deeded ground and about 200 hectares (490 acres) of leased pasture. The ranch is divided in the middle by a county gravel road, with the corrals on the north side of the road near the gate for moving bison from pasture to corrals (Fig. 1). Lame Johnny Creek flows in the spring most years but has flowed year long on occasion. Soils are deep to shallow, undulating to hilly, and textures range from loamy to sandy (South Dakota Rangeland Resources 1977). The creek has a mixture of elm (Ulmus sp.) and ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica) trees. Dominant grass species of western wheatgrass (Agropyron smithii), big blusteam (Andropogon gerardii) and blue grama (Bouteloua gracilis) occur on most of the land (Johnson 1999). 7 Figure 1. Hurst Ranch located in Custer County, roundups in years 1994 and 1995 During the first year of this study, 1994, a roundup of > 80 animals involved 5 people in pickup trucks and all-terrain vehicles (ATV’s) gathering and herding the animals from a 100-hectare (250 acre) pasture. The animals were brought down along the south east running fence line toward the fence line along the road circling back to a gate in the corral (see Fig. 1). It took about 4 hours with experienced bison wranglers to complete the capture, which developed into an aggressive chase. 8 During the second year, 1995, 5 people were again involved in the roundup. This time, using only ATV’s, the animals were brought along the same fence lines to the same corral entrance as in the first year. More effort was made during the summer to entice the animals to enter the corral, using water and grain pellets for bait. Despite increased effort of getting the animals comfortable with entering the corral, the roundup took over 2 hours. After examining the layout of the pastures and how the animals were moved in a pasture rotation grazing plan, a short fence (Item A in Fig. 2) of about 150 meters (500 feet) was built to divert the herd through the corrals after crossing the road from south to north (Fig. 2) rather than entering the pasture and merely passing by the corral. Following this plan, bison were sent through the corrals three times in year 3, 1996, in the normal pasture rotation, when moving the herd to the north pasture between 1 May and 1 October. RESULTS ON LAME JOHNNY CREEK RANCH The roundup began in the south pasture, which was approximately 150 hectares (370 arces) with three wranglers on ATV’s. The bison were herded, mostly at a walk, to the gate crossing and corral. The total process to gather and corral the bison herd required approximately 30 minutes. Once in the corral, the bison stood quietly while preparations were made to sort and vaccinate animals. During subsequent years, Mr. Hurst would 9 gather the herd from the south pasture on the Lame Johnny Creek Ranch alone prior to having help arrive to work the bison; the bison rested quietly until the crew arrived. Figure 2. Hurst Ranch Located in Custer County Roundups after addition of fence A in 1996 CHEYENNE RIVER RANCH Hurst Ranch Cheyenne River is located approximately 55 km (34 miles) south east of Rapid City. The land is flat with clayey soils with some silty shale soils (South Dakota 10 Rangeland Resources 1977). The south pasture is dominated by Cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum), while the balance of the pastures is dominated by Sideoats grama (Bouteloua curtipendula) and Blue grama (Bouteloua gracilis) (Johnson 1999). Fences were improved to a 6-barb wire 1.3 meter (5 feet) high fence. The existing cattle corral was partially refitted to handle bison, but the design for roundup was primarily left in place. The corral was located in the corner of a road-accessible pasture and near two other pastures (Fig. 3). The pasture with the corrals and barn was approximately 240 hectares (590 acres) in area, the south pasture approximately 320 hectares (720 acres), and the pasture to the east was 100 hectares (250 acres). Figure 3. 2002 & 2003 Roundups at Cheyenne River Ranch located in Pennington County 11 The herd was increased to over 250 bison. During the first roundup in 2002 (Fig. 3: year one diagram), the animals were brought down the fence line to the east of the white barn and around into the corrals. These corrals were mostly of portable design. Three wranglers directed the herd into the corrals for this first roundup. The expertise of the handlers kept the herd from breaking away, allowing for roundup of bison from a 240 hectare (590 acres) pasture in approximately one hour. During the second year, 2003, two attempts were required to capture the herd. The first attempt was from the east side of the barn, as in the previous year, the second attempt was along a fence to the south and west of the barn (Fig. 3), which was successful and took about two hours with three wranglers on ATV’s. RESULTS ON CHEYENNE RIVER RANCH This more difficult roundup pressed the point of repeating the process of the Lame Johnny Creek Ranch, which involved construction of a 200-meter (650 feet) fence (Fig.4: fence B) leading from a south pasture to the corrals and through the pens out to the north pasture. Throughout the next year, 2004, Mr. Hurst moved the herd through the corrals from the south to the north twice without capture (See Fig. 4:herd travel diagram). That fall, Mr. Hurst completed his fall roundup of over 250 head of bison alone the evening before the wranglers arrived to process the animals for the year. Mr. Hurst repeated the 12 same process in year four and completed the bison roundup again by himself in 30 minutes. This “training” process was repeated on two different ranches with two different herd sizes with the same result. Training of bison (Lainer and Grandin 1999) can happen with very few training trips to make handling of bison much less stressful, as well as safer and more humane for animals and humans alike. Figure 4. 2004 Roundup after addition of fence B, Cheyenne River Ranch RESULTS and DISCUSSION 13 Bison roundups tend to be one of the more difficult processes in bison ranching. In surveys conducted for the National Bison Association one of the top issues of greatest concern among ranchers involved handling bison and corral designs. Over the years, prospective and active bison ranchers have looked at wildlife professionals to establish methods of handling bison. The primary methods of driving herds to traps has changed little going back to what Native Americans used prior to the Europeans landing in North America. Updates have evolved from canyon walls to modern day fencing materials of barbed and woven wire to sheets of steel. Methods of chasing the animals have gone from humans on foot to horseback riders to pickups and aircraft. When herds are driven to the same corral every year the methods of forcing the animals into the corral become more dramatic because of the animals memory of the stress that occurred the last time they were driven into the trap. On each of the ranches in this study, when the animals brought into the corral once a year they were difficult to corral. Even when the animals were allowed into the corrals at will they sensed a trap when the roundup crew started the chase. In contrast, when the same herd was brought through the corral two or more times per year without being worked in the chutes, the “training” proved to be a method that allowed a single person to move a herd of 250 bison into the corral with low stress. 14 In each of the corrals, the animals had to go through more than one gate to get to the final pen. By virtue of the animals traveling through two or more gates as part of the move between pastures, they could not see that the gate was closed on the exit pen until arriving in the last pen. It was at this point where the animals under traditional roundup methods would turn to come back out of the pen and an all out effort to hold the herd would occur. However, bison herded into the pen as part of a normal pasture move would wait calmly for the gate to be opened for exit. 15 CHAPTER 3 ENTERING READY CHUTES INTRODUCTION Ready chutes hold animals before they enter the squeeze chute where they are held for processing. Many private and public bison operations use tractors with push gates to bring the animals up to the ready chutes. From there crowding gates are used to force the animals into the ready chutes. The objective of this study was to identify methods that allow bison to enter the ready chutes easily and to determine if bison visualize the ready chute as an exit rather than a closed “canyon”, which would cause animal to resist entrance. METHODS An opportunity to analyze design variations that decrease resistance of bison entering ready chutes was presented when a neighboring bison rancher, Preston’s, needed help working their herd. The Preston operation, located two miles north of Hermosa, SD would be set up within a fixed corral but with the ability to vary the position of the ready chutes (see figs. C and D in equipment description section) in relation to the working tub (Fig. B in equipment description section) entrance into the ready chutes. In comparison, the 777 Ranch facility, located eight miles south of Hermosa, SD, is a more permanent set up. The crowding tub at both facilities consisted of the same design and had the same type of gates and panels. There were a nearly equal number of animals to be worked through each facility. 16 Each facility had a similar process where bison would pass the end of the ready chute to enter a holding pen and then return into the tub area to enter the ready chute (B. Williams, Stockmanship Course, 1991). The 777 Ranch chute entrance was set at a 90degree angle from the alley staging area (Fig. 5), while the Preston Ranch chute was set at approximately an 85-degree angle from the direction animals were staged but also offset from the edge by approximately 30 cm (1 foot) (Figs. 6a and 6b). In both facilities, the gate that closed behind the animals latched nearest the entrance to the ready chutes. It was postulated that the animals seemed to see the last opening as the gate closed (latch is at point A in Figs. 6a and 5show latch point in each picture) and traveled to this corner first when they returned to the tub area. This was consistent with both herds of bison, with the lead animals all going to that corner of the pen. This would seem to position the animals well to see the opening into the ready chutes with their left eye looking into the chute opening. On 18 March 2005, 101 head of bison were processed through the chutes at the 777 Ranch corrals. The bison were brought into the holding pen (Fig. 5) in groups of 20-30 head. They were then brought through the tub area 4-6 head at a time. Animals were never held in the tub at either ranch. For the 4 animals that failed to enter an available crowding gate was used, at the 777 Ranch. 17 On 22 March 2005, a group of 70 bison were processed at the Preston Ranch. Animals were brought into holding in groups of 20-28 head. Groups of 3-4 animals were then moved through the tub area. The entrance to the ready chute at the Preston Ranch was turned back slightly and was offset 30 cm (1 foot) (see Fig. 6, point A). The offset was to accommodate the sliding gates on the back of the ready chute that would allow entrance of the animals. A Chi Square analysis was used to compare the distribution of animals entering the ready chute at the two ranches. 18 Figure 5. Calf movement in 777 Ranch corrals located in Custer County. 19 Figure 6a. Preston corral design, showing animal movement through pens and back to crowd pen for entry into ready chutes. Figure 6b. Preston corrals showing direction of movement into ready chute 20 RESULTS and DISCUSSION As the bison at the Preston Ranch were brought into the chute in groups of 3-4 head, they would consistently look at point A (Fig. 6b) then turn to the other end apparently looking for an opening. It seemed the animals saw the opening; in fact, placement was located so that their left eye (R.Huhnke, Great Plains Beef Cattle Handbook GPE-5002) looked directly into the chute, but the bison still turned to the other end of the pen to look for an exit. Only two bison of the 70 head processed entered immediately. In contrast, bison in the 777 Ranch corral entered the chute readily. Of the 101 bison processed, only 4 head failed to enter the chute immediately after passing through the tub area (Table1). At the 777 one person followed the bison up on a catwalk on the inside corner (Fig. 5). TABLE 1. The number of bison entering and resisting entrance to ready chute at 777 and Preston ranches. 777 Ranch Numbers entering immediately: Numbers resisting entrance: Preston Ranch 97 head 2 head 4 head 68 head Statistical Analysis: Yates Corrected Chi square: (X²=143.473, df=1, P<0.001) 21 The 30 cm offset seemed to be the primary factor inducing resistance. The animals seemed to focus more on the gate closure point, then proceeded to the other end of the gate before returning to the chute entrance area. Even though it would seem that the side set eye of the animal should allow a clear view of the chute entrance it did not seem to be a factor in this instance. The Preston Ranch set up was constructed with a mixture of portable equipment and fixed gates but was of identical design to the type of panel, gate, and gate latches used at the 777 Ranch. Results indicate that slight differences can have a marked effect on how animals move through a facility. The alley gates on the back of the ready chutes latched near the entrance to the ready chutes. It has been noticed that bison seem to go to the corner where they last saw an opening. It is possible they see the opening close behind them using their peripheral vision from their wide set eyes. 22 CHAPTER 4 TRAINING BUFFALO TO LOAD INTRODUCTION Loading bison onto trucks or into stock trailers can be difficult. The loading area is usually enclosed and may resemble a cave or canyon. Bison could respond negatively to entering trailers because of an innate fear of predators (Kleuver et al. 2009). The goal of this effort was to see if bison would readily enter the trailer as opposed to being crowed into the trailer, using minimal training. METHODS In mid-October 2006, we sorted 2 and 3 year-old bison females away from the main herd to be sold. Half the herd was rounded up and the 2 and 3 year-old females sorted off during the first week of October and the second half of the herd was sorted during the second week of October. In each case, the animals were gathered into the main corral the night before sorting. Sorting of the animals was conducted in the morning with bison loaded into two semi-truck livestock pot trailers in the evening. The animals were sorted through a corral system (Fig. 8). This was a complete mixedage herd with mature bulls, cows with calves, yearlings, and two year olds. The animals were brought into the tub area in small groups of 5-10 bison depending on size. They were brought back into the ready chute area and sorted into one of three pens: one each 23 for calves, 2 & 3 year old females and breeding herd adults. A Chi Square analysis was used to compare the frequency distributions of bison relative to their entering the loading chute. Figure 8. Animal travel path through corrals for sorting and location of loading chute & truck. 24 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION Week one: Week 1 sorting resulted in 114, 2-3 year old bison females. A portable chute was placed at the end of the tub area for loading the trucks. The 2-3-year-old bison females were brought up to the trailer in groups of 4-12 head depending on the pen size in the semi trailer. The animals consistently went to the end of the tub where the loading chute entrance was located (Fig. 8) turned and tried to go back to where they had left the tub earlier in the day. Only 5 animals saw and entered the . loading chute on first arrival to the entrance, while the balance of 109 animals seemed not to see the loading chute entrance. Week two: Week 2 sorting resulted in 112, 2-3 year old bison females. The same process of sorting occurred as in week one. At the end of the sorting process all gates through the tub (Fig. 9) were opened and the animals herded through for one pass and returned to their holding pen until the trucks for load out arrived. The loading chute was placed in the same location as week one (Fig. 8). Again animals were brought into the tub in groups of 4-12 head to accommodate trailer pen sizes. In this trial all but 4 animals entered the loading chute readily without turning back to the ready chute area. 25 Figure 9. Training Trip through corrals before loading. TABLE 2: Change in resistance to loading before and after training. Readily entered Resisted entering loading chute loading chute Week 1 group 114 head 5 Week 2 group 112 head 106 Yates Corrected Chi square: (X²=185.795, df=1, P<0.001) 109 4 26 The one trip through the open gate on the end where the loading chute was located greatly increased the ease of loading. Time to load bison was less than an hour compared to two hours to load the first two trucks without training of bison. Animal confusion related to where they thought they could go and the time to get them directed to see and go up the chute were factors in the increased time to load the first two trucks. Weather conditions were nearly identical, the people who helped with loading, and the two trucks were the same on each set of loading samples. Our only significant change was the walk through the loading area before loading. Also noticed was the ease of the animals from week 2 entering the entire tub area. Week 1 bison that did not have the walk through training, resisted movement into the tub area and had to be pushed into the tub area using crowding gates, sorting sticks, and rattle paddles. Week 2 bison that had the walk through training moved right to the loading chute. In fact, the crowding gates were used to hold back or limit the necessary numbers entering the tub while loading the semi-trailer. There was no need for rattle paddles or poking to encourage animals to enter and move up the chute. By allowing the bison a walk through (Lanier 1999, www.grandin.com, 2007) they likely saw the end of the pen as an escape while those that did not have the walk through training had the experience of no escape at the end of the pen, and by previous experience knew they had to go back to escape the area. 27 CHAPTER 5 BISON WORKING CHUTE CRASH GATE TESTS INTRODUCTION Over the past 30 years I have handled countless bison, often in excess of 2,000 head per year. I have made numerous changes and modifications to chutes, corrals, fences, design, and handling procedures based on a combination of trial and error and observation. This study involves the crash gate on the bison working chute. The crash gate is located about 25-30 cm (10-12 inches) in front of the headgate that holds the animal by the neck. With horned animals and in particular with the speed and power of the bison, the crash gate stops the animal long enough to close the head gate on them. With headgate set at a wide opening to allow the horned animal through, and no crash gate, it is not uncommon for the bison to be through or past their shoulders by the time the headgate is closed. This is not a position that will sufficiently hold the animal, so the animal would have to be let go without being processed, regardless of whether they were held for testing, vaccination, or treating a condition. Crash gate designs include: bars, solid front, solid plate, slant back bottoms with the aforementioned designs, and solid with a window at eye level both open and with a lexon insert. The objective of this study was to compare solid and solid with a window crash gate designs and safety and effectiveness in getting the animals to enter the headgate. 28 Previous experience tells us that the bison will crash into gates that have bars only; hence, the name “Crash Gate”. As a consequence, we did not use that design. METHODS Having observed bison with each of the aforementioned crash gates designs, we selected two designs that seemed to create the least chance of injury to bison. The chute used for this study was a Berlinic (Berlinic Manufacturing, Quill Lake, SK, Canada) at Custer State Parks buffalo corrals, which is specifically designed for bison (Lessard et al. 2009). The crash gate has a solid front with open sides and top with a feature that allows the operator to move the crash gate varying distances from the head gate depending on the size of the animal entering the chute. During this study, the distance was set the same using site bars on the side of the crash gate, and the top and sides were covered with a translucent like cloth. This allowed light into the crash gate and we hoped it would allow the bison a greater focus on the front of the gate (Figs. 10 and 11). Our hope was for the bison to enter with little hesitation but not hit the crash gate. The Berlinic chute comes with a solid front. We modified the crash gate so that we could easily remove the solid front and inset a lexon, a transparent Plexiglas type material that would allow the animals see through the crash gate. Modifications to the crash gate were as follow: Window location and size; 29 Distance from the chute floor to the window bottom: 60 cm (2 ft) Window dimensions: 40 centimeters in height by 70 cm (2.3 ft) wide Window Material: 0.60 cm (2 ft) Lexon (this is a Plexiglas type material that can sustain a hit from a hammer without cracking) Figure 10. Front View of Crash Gate. Figure 11. Side view of crash gate A total of 91 male and female bison was processed. The front panel (Lexon vs. solid) was changed after each set of 10-12 bison were processed. Justification for set changes 30 revolved around the idea that animal responses may change the longer they were handled in the back pens before getting to the headgate. Entry of bison into the crash gate was rated as follows: Hit- the animal entered ramming into the front crash gate. Good- the animal entered quickly to the point where the head gate could be closed with less than 5 second hesitation without hitting the crash gate. Hesitated - the animal hesitated from 5-10 seconds before entering without encouragement. Push - the animal pushed into the crash gate but did not ram it. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION From a percentage stand point, animals entering in the good category with the Lexon window totaled 71 percent compared to 10 percent with the solid front (Table 3). Size of the window seemed to be an important part of the setup. It provided enough light and sight for the animal to go to, but was small enough for them to restrict travel through the window. When using the solid front, almost half of the animals hit the crash gate, which seems to counter what we would expect in a corral setting. A solid fence in a corral would not be jumped or rammed except under extreme pressure from flight. The chute setting was more confined and extreme but our research did not examine this aspect. Toward the end of working these bison, we removed one of the side panels to evaluate 31 effects of additional open space on movement of bison into the crash gate. Animals immediately went for the open as opposed to the solid panel. Thus, opaque sides might be beneficial but further study is needed to confirm these observations. TABLE 3: Levels of acceptance and resistance to entering a squeeze chute. Hit Good Lexon 9 36 Solid 19 Hesitate 4 3 15 Push Total 3 51 2 40 Total 91 head Row Percentages Lexon 17% 71% 6% 6% 100% Solid 48% 10% 37% 5% 100% No. of Animals 28 hd 40 hd 18 hd 5 hd Test Statistic Value df Pearson Chi-square 30.52 3.00 0.00 Likelihood ratio Chi-sq 32.84 3.00 0.00 = 91 head prob Concerning the slant back bottom on many crash gates, while I understand the principle that if the animals get their front feet through the head gate they will slide back, I believe 32 the design to be dangerous to bison. When an animal loses its footing, it increases stress. It is much better to have the animal step through and step back without loosing its footing (T Grandin, personal communication). Although this issue has not been tested, serious thought should occur before purchasing a crash gate with the slant back bottom. CONCLUSIONS and DISCUSSION Moving bison through various natural or man-made corridors seems to have a positive effect on lowering stress during roundups in these same areas. The animals have identified a more positive relationship with moving through corrals than negative as it allowed them access to fresh grass. While feeding bison in a corral would seem similar, the animals likely sense a trap, which resulted in a fear response (Kluever et al. 2009). Allowing the bison in the loading chute for one “training” trip to establish direction of movement, made a great difference in reducing loading time, effort expended, and presumably, stress on the animals. In the ready chute work, the point where bison sense that day light has become limited is when closing a gate, which has been reinforced by watching animals move to solid gates after they have closed as they go to the latch end of the gates first. The wide set eyes on bison allows them a wide peripheral view. The animals also will turn their head slightly when moved up allies so that they can see directly behind them at a herdsman or object moving them along as when a herdsman uses a flag on a stick, which adds to this ability to notice gate movement. 33 There were other points of interest in handling the bison in close quarters. Putting a flagged stick in their face to turn them in a desired direction was not effective. Touching them on the rump would result in bison turning 180 degrees to look for the threat and often resulted in a change in movement to the opposite rather than the desired direction. The best location to touch a buffalo to move them forward is on or slightly behind their shoulder. The shoulder is the balance point of movement ( Grandin, T., Williams, B., personal communication). This becomes more obvious to the handler while handling an individual animal in a pen or when moving along a chute runway the handler will notice the animal most often will move forward once they pass the shoulder. 34 Two Loading Chutes Examples Loading chutes use a ramp with sides, often of similar width to ready chutes, to guide animals into trucks for transport. Ramp height is 1.2 meters (4 ft) above ground level. Animals often enter loading chutes via crowding tubs. 35 Tub/Crowding Tub Leads to ready chute or loading chute. The tub can be ¼ to ¾ circle with a radius that varies greatly. The tub in the picture above has a 4 meter (12 foot) radius with a ¼ circle. The sweep gate is used to gradually crowd the animals to the entrance of the ready chute. 36 Ready Chute Entrance So called because is holds animals ready to enter the squeeze chute in the front. Ready chutes may hold one to several animals in the ready. For most adult animals the chute is 71 cm (28 inch) inside width. This will hold animals in a weight class range of 300 kg – 800 kg (760-2,000 lbs) in a single file without being able to turn around inside the chute. 37 Ready Chute Side View With bison the ready chutes are further compartmentalized to a length of 2.4 meters (8 ft) to hold the animals individually. Because the bison are usually horned, this reduces the chance of injury to the animal in front from being gored, jumped, or stepped on because it is has little means of defense. 38 Squeeze Chute with Crash Gate The squeeze chute is a single stall with sides that move in to put a light squeeze on the animals to hold the bison still to perform various procedures. This is supplemented by a head catch gate that holds the animal by the neck to gain access to the head and further immobilize them. Procedures might include; tagging, vaccinations, pregnancy testing and blood samples. The crash gate is used to keep the bison from getting through the head catch. Because of the animals horns the head catch must be held open wider than the width of the horns. Because of the speed and strength of the bison many would get through without the crash gate to stop them. 39 LITERATURE CITED Bison Breeders Handbook. 2001. 4th Edition. National Bison Association. Bragg, T. K., B. Hamilton, and A. Steuter. 2001. Guidelines for Bison Management. 2nd Edition. The Nature Conservancy, Arlington, Virginia. Corner, A. H., and R. Connell. 1958. Brucellosis in bison, elk, and moose in Elk Island National Park, Alberta, Canada. Canadian Journal of Comarative Medical Veterinary Science 22:9-21. Firmage-O’Brien K. 2008. Bison on the comeback trail, 2006 Census of Agriculture, http://www.statcan.ca/bsolc/english/bsolc?catno=96-325-X200700010504; 2006 [accessed on October 10, 2008]. Grandin, T. March 1, 1998. Directions for Laying Out Current Cattle Handling Facilities. Beef pp 50-52. Grandin, T. 1989. Behavioral Principles of Livestock Handling. Professional Animal Scientist, pp 1-11. Grandin, T. Buffalo Handling Requirements; website: www.grandin.com Grandin T. Design of Ranch Corrals and Squeeze Chutes for Cattle; Great Plains Beef Cattle Handbook. GPE-5251.1-5251.6. SDSU Research and Extenstion. Grandin, T., Recommended Truck Loading Densities. www.grandin.com Hart, R.H. August 1983, A Sorting Corral System for Livestock Production or Research; Rangelands, 5 (4) Hauer, G., and L. Helbig. 2005. Bison Handling Facilities. Alberta Agriculture, Food and Rural Development, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. Huhnke, R.H., and S. Harp, 1974, Corral and Working Facilities for Beef Cattle; Great Plains Beef Cattle Handbook, GPE-5002.1-5002.6 Jenning, D.C., and J. Hebbring, 1984, Buffalo Management and Marketing; pp 33-68, 1st Edition, National Buffalo Assoc. Fort Pierre, SD Keiter, R. B. 1997. Greater Yellowstones’s bison: unraveling of an early American 40 Kluever, B. M., L. D. Howery, S. W. Breck, and D. L. Bergman. 2009. Predator and heterospecific stimuli alter behaviour in cattle. Behavioural Processes 81:85-91. Lanier, J. and T. Grandin, Oct. 1999, Training American Bison Calves www.grandin.com, 2007 Lessard, C., J. Danielson, K. Rajapaksha, G. P. Adams, and R. McCorkell. 2009. Banking North American buffalo semen. Theriogenology 71:1112-1119. Patterson, M. 2004. Behavior Management and Handling Facilities Design for Bison. Industry Specialist, Saskatchewan Bison Association, Saskatchewan, Canada. Roe, F.G. 1951. The North American Buffalo, A Critical Study of the Species in its Wild State. 1stz Edition University Toronto Press, Toronto, Canada Smith, B. 1998. Moving Em, A Guide T Low Stress Animal Handling. The Graziers Hui, Kamuea, Hawaii.