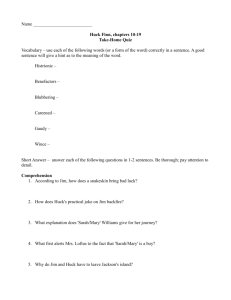

Huck Finn Lit Chart

advertisement