Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

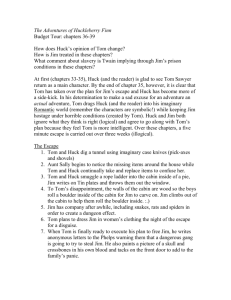

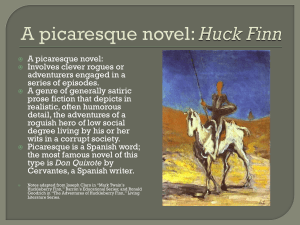

advertisement

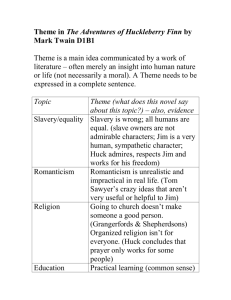

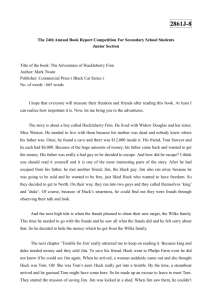

“Jim, he couldn’t see no sense in the most of it, but he allowed we was white folks and knowed better than him.” Like Huck, Jim has been so conditioned by a slave-holding society, he never questions the morality of slavery. Only the threat of permanent separation from his family compels him to run away. Since he believes the lowliest white person is still his social superior, it seems logical to him that Tom Sawyer must also be his intellectual superior. While funny, all of this escape material is very cruel to Jim, who has the status of a stage prop in Tom’s mind. Jim doesn’t know the escape is a charade; he goes through all of these complications because he thinks they are necessary to gaining freedom. Twain is making fun of Tom and by extension, people who think like Tom. The coat of arms scene is Tom at his worst. This is a parallel to the Duke’s rendition of Hamlet. What’s more, it’s not even rebellious: Tom knows all along that Jim is a free man: He is not trying to help a slave escape. The escape is indeed splendid from an adventure point of view. Jim’s refusal to leave Tom untended is extremely noble, especially given how badly Tom has treated Jim over the past three weeks. Huck sees Jim as “white inside.” Huck’s definition of blacks as property hasn’t changed, and he has barely given any thought to the larger social issue. What has changed is his attitude toward an individual black man, who has evolved in Huck’s mind from a piece of property to an admirable human being. As much as these people seem to care for Huck, he isn’t at all sure he belongs with them – or any other people, for that matter. He’s had some good glimpses of civilization on his journey, and most of what he’s seen hasn’t been very pretty. So the last thing he says is he intends to light out for the territory – that part of the country that hasn’t yet been “blessed” with civilization. In the 20th century, critics angry about Twain’s realistic language and impatient with his ironic condemnation of racism, have accused him of it, confusing the messenger with the message. Lost in the serious issues is that Huckleberry Finn is a very funny book, told in deadpan. Huck is entirely humorless: only Twain and the reader “get it.” Readers lulled by Huck’s voice just talking his story, and lulled by Twain’s loving evocation of the sights, sounds, and smells of idyllic life on and along the river, are sometimes jolted by the discomfort they feel at Huck’s language, and at the people and incidents Huck encounters – including the violence of Pap Finn, the feud between the Grangerfords and Shepherdsons, the murder of Boggs, the bilking of the orphan Wilks girls, and the betrayal of Jim. They all belong to a world profoundly flawed and uncomfortably real. Because in its plot and its narrative details the book brings up issues of class , violence, and racism in American society, and because these issues are still with us, the book remains almost as controversial as it is celebrated. In the 19th century, critics were shocked at Huck’s “low” language, his rationalization of lying and stealing, and his undisguised skepticism toward such things as prayer and religious doctrine. They sought to ban the book, lest it set a bad example for children. Initial reviews were equally mixed: Some “got it,” and others didn’t: • “It deals with a series of adventures of a very low grade of morality; it is couched in the language of a rough, ignorant dialect, and all through its pages there is a systematic use of bad grammar and an employment of rough, coarse, inelegant expressions. It is also very irreverent.” • Others called it the crowning achievement of a “literary artist of a very high order,” a “tour de force,” a “minute and faithful picture,” and hailed its evocation of the “lawless, mysterious, wonderful Mississippi” and of the “startlingly real” riverside people who “do not have the air of being invented, but of being found.”