Fair Housing and Housing Access Briefing Paper

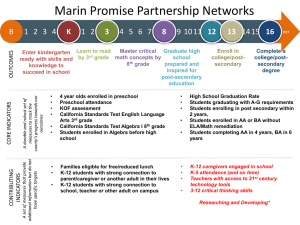

advertisement

To: Action Coalition for Equity From: Elisabeth Voigt, Senior Staff Attorney, Public Advocates Inc. Date: February 8, 2013 Re: Fair Housing and Housing Access Briefing Paper ______________________________________________________________________________ I. Introduction Advocates for social equity and racial justice in Marin County share a common vision for a just Marin. They envision a Marin where all people, regardless of race, ethnicity, or any other protected status, have access to housing they can afford, schools that prepare their children to meet their potential, jobs that pay a living wage, reliable public transportation, and all the other building blocks of a thriving community. To realize this vision, advocates who have come together as the Marin Action Coalition for Equity (ACE) face short- and long-term opportunities to ensure that all community members, residents, and workers share in the County’s prosperity. As ACE prioritizes the opportunities it will pursue to advance this vision, it is timely and instructive to step back to survey civil rights struggles of the past, the strategies that have led to wins, and the legacy of segregation that still persists. This briefing paper provides a history of fair housing obstacles and struggles, an overview of the obligation to Affirmatively Further Fair Housing, and a summary of the current state of fair housing in Marin. We hope it will provide ACE with useful background as it makes decisions about setting and undertaking a robust and effective set of fair housing strategies to make Marin a stronger and more inclusive community. II. Housing and the Civil Rights Struggle Open access to housing and residential integration have long been a central part of civil rights struggles in the United States. Within the Civil Rights Movement, Dr. Martin Luther King, leaders of the NAACP, and many unsung civil rights heroes built strategic campaigns to fight housing discrimination and segregation using organizing, advocacy, and litigation. They chose to target housing because from the post-Reconstruction era through Jim Crow discrimination in housing was a dominant instrument of racial oppression. In the early 1900s, when African Americans left the South to escape violent oppression in the Northern Migration, white communities reacted with prejudice and hate. To keep those African American families out of their neighborhoods they adopted racially discriminatory housing policies. Following trends in the South, Northern and Western cities adopted zoning codes for the very purpose of designating 1 neighborhoods by race, prohibiting blacks and whites from living together.1 And when explicit racial zoning was outlawed, many white communities turned to other means to reach the same racial results, including private agreements called racially-restrictive covenants that prohibited the sale of homes to African Americans. Along with discriminatory laws and contracts, some cities reacted with violence — “white residents responded to the arrival of black families with riots, home bombings, and cross burnings.”2 The federal government reinforced these exclusive, segregative practices through its policies and investments. Federal redlining policies denied African Americans home loans, while the first public housing projects were explicitly segregated by race. The federal government’s massive investment in transportation infrastructure allowed highways and commuter rail lines to be built through African American communities so that white families who had fled the cities to live in exclusive white suburbs could get to white collar jobs downtown. These investments not only did not benefit black families in communities of concentrated poverty in cities, but displaced and further isolated them.3 Throughout the 20th century, civil rights leaders and community members pushed back on these racist, oppressive policies and practices with strategy and strength. Beginning in the early 1900s, the NAACP developed a comprehensive legal strategy to challenge racial segregation in schools, employment, public accommodations, voting, and housing, leading to the 1954 landmark civil rights victory in Brown v. the Board of Education.4 As part of that legal campaign, in 1945, the NAACP challenged racially restrictive covenants, which had been a widespread measure used to exclude African Americans from many white neighborhoods. The case came about when an African American man named J.D. Shelley and his family bought a home in St. Louis that was covered by a racially restrictive covenant. A white owner of another property in the neighborhood sued to force the Shelleys to move out. After planning for decades to mount a challenge to racially restrictive covenants, Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP stepped in to make the case that such restrictions were unconstitutional, and they were victorious. In 1948, the Supreme Court held that a state’s enforcement of restrictive covenants violated the 14th Amendment equal protection rights of black homeowners.5 Despite these early legal victories, civil rights leaders knew litigation alone was not enough. With each legal challenge, racist practices shifted and new challenges arose. For instance, after the Supreme Court mandated the integration of schools in Brown v. Board of Education, residents of exclusive white communities clung to measures that kept black families out of their neighborhoods in order to keep black children out of their schools. Recognizing the need for multiple strategies, civil rights leaders fought to change oppressive policies through organizing and advocacy efforts at every level of government. Their efforts faced strong resistance and many losses. Even in Berkeley, a proposed law to ban discrimination in real estate sales was blocked in 1963. One of the Council’s liberal African 1 See Christopher Silver, The Racial Origins of Zoning in American Cities, in URBAN PLANNING AND THE AFRICAN AMERICAN COMMUNITY: IN THE SHADOWS (Manning Thomas, June and Marsha Ritzdorf eds., 1997). 2 Nikole Hannah-Jones, Living Apart: How the Government Betrayed a Landmark Civil Rights Law, PROPUBLICA (Oct. 28, 2012), available at http://www.propublica.org/article/living-apart-how-the-government-betrayed-a-landmark-civil-rights-law. 3 Id. 4 See National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Legal History, http://www.naacp.org/pages/naacplegal-history. 5 Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (U.S.). 2 American members said that the measure’s failure had shown that “Berkeley’s whites had said, ‘It’s all right to have a brother of any color, but I don’t want him on my block.’”6 Despite this resistance, organizing strategies led to critical policy wins. In the 1940s and 50s, East Bay NAACP leaders, including C.L Dellums, the uncle of former Congressman and Oakland Mayor Ron Dellums, built institutions in black communities, organized communities, and strategized to end discrimination in employment and housing. Joining forces with labor unions and Byron Rumford, California’s first African American statewide elected official, in 1959, the NAACP won the passage of the Fair Employment Practices Act, which outlawed employment discrimination. And in 1963, Assemblyman Rumford introduced a fair housing bill, which became known as the Rumford Fair Housing bill.7 Although the bill faced strong opposition — including a statewide referendum that temporarily repealed it until the courts stepped in — with strong organizing and lobbying tactics, it eventually passed.8 At the national level, as legally-sanctioned segregation started to crumble in the 1960s, civil rights leaders turned their attention from Jim Crow in the South toward the growing problems of stark racial segregation in the North. The first large scale housing campaign in the country was the 1966 Chicago Freedom Movement. Despite numerous obstacles –– from resistance by city leadership to violence in black communities to growing fissures among movement leadership – Dr. King brought together black residents, white allies, gang members, and clergy and led a series of marches in the white neighborhoods of Chicago. Marches were not the only tactic used, however. At the same time, a group of Chicago public housing authority residents filed Gautreaux v. Chicago Housing Authority, alleging that the housing authority and HUD’s practice of concentrating public housing units in segregated neighborhoods and preventing blacks from moving into white developments violated the Constitution and various civil rights laws. And activists started testing for housing discrimination in white neighborhoods. The neighborhoods where discrimination was most rampant became the focus of the Freedom March’s protests. 9 The Freedom Movement faced horrific violence from white residents. During one of these marches 500 participants faced 4,000 angry white protesters. Dr. King declared that he had “never seen as much hatred and hostility on the part of so many people.” But the violence did not deter the Freedom Movement; eventually Chicago’s Mayor Daley agreed to sit down with the movement leaders and together they struck an agreement. “Certainly the Chicago Freedom Movement did not succeed in its grandiose aim of ‘ending slums,’ but …it succeeded in dramatizing the plight of black inner-city residents, and it proved that nonviolent direct action could be successfully adapted to the northern urban setting.”10 III. The Passage of the Fair Housing Act 6 STEPHEN GRANT MEYER, AS LONG AS THEY DON’T MOVE NEXT DOOR: SEGREGATION AND RACIAL CONFLICT IN AMERICAN NEIGHBORHOOD 179 (2000). 7 ROBERT O. SELF, AMERICAN BABYLON: RACE AND THE STRUGGLE FOR POSTWAR OAKLAND 82-95 (2003). 8 Id; MEYER, supra note 6, at 262-63. 9 Poverty Race Research Action Council (PRRAC), Launching the National Fair Housing Debate: A Closer Look at the 1966 Chicago Freedom Movement, available at http://prrac.org/full_text.php?text_id=1047&item_id=9645&newsletter_id=0&header=Current%20Projects. 10 Id. 3 Thanks to the strategic work of the Civil Rights Movement great gains were made in federal anti-discrimination laws. In the wake of the Brown decision, in 1964, President Johnson signed into law the Civil Rights Act, which outlawed discrimination in employment, public education, and public accommodations. Just a year later, he signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965. But these major civil rights advancements did not address housing or residential segregation. This was because “the Fair Housing Act was the most contentious of the civil rightsera legislation, blocked for years by Northern and Southern senators alike.”11 While white Americans and political leaders seemed prepared to offer a degree of racial equality in schools and jobs, they refused to dismantle the deliberately constructed residential segregation patterns that reinforced America’s racial caste system.12 As discussed above, white homeowners pushed hard for exclusionary housing policies and refused integration efforts. With such an entrenched racist reliance on separate and unequal housing opportunities it is not surprising that numerous attempts to pass the federal Fair Housing Act failed. In 1968, frustrated by the failed attempts to pass a federal fair housing law and deeply concerned by the riots erupting in over 100 cities across the country, President Johnson created a blue ribbon panel to study the urban riots and make recommendations. This panel, called the Kerner Commission, concluded that housing segregation — and the creation of “two societies, one black, one white – separate and unequal” — is what caused the riots.13 The report blamed racist attitudes by whites for the outbursts in America’s cities, stating, “white society is deeply implicated in the ghetto. White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it, and white society condones it.”14 With that finding, the commission called for a federal fair housing law. Four days after the release of the Kerner Commission report, Dr. King was assassinated and riots erupted again. With the city around the Capitol literally burning, Congress finally passed Title VIII of the Civil Rights Act, the Fair Housing Act. IV. The Duty to Affirmatively Further Fair Housing A. The Meaning of Affirmatively Further Fair Housing The Fair Housing Act declares it to be “the policy of the United States to provide, within constitutional limitations, for fair housing throughout the United States.”15 It prohibits discrimination in the sale, rental, and financing of housing, and in the provision of other housingrelated services, because of race, color, national origin, religion, sex, disability, and familial status.16 In addition to prohibiting discrimination, the Fair Housing Act mandates affirmative steps. It requires the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development to “administer the programs and activities relating to housing and urban development in a manner affirmatively to further the 11 Hannah-Jones, supra note 2. MEYER, supra note 6, at 134-35. 13 REPORT OF THE NATIONAL ADVISORY COMMISSION ON CIVIL DISORDERS (KERNER COMMISSION REPORT) 1(1968), available at http://www.eisenhowerfoundation.org/docs/kerner.pdf. 14 Id. 15 42 U.S.C. § 3601. 16 See 42 U.S.C. 3601, et seq. 12 4 policies of [the Fair Housing Act].”17 This is the source of the phrase “Affirmatively Further Fair Housing” or AFFH. The law itself does not define AFFH or further spell out the purposes of the Fair Housing Act. However, the statements from Congressional members as they debated the law shed some light on the meaning. The record makes clear that Congressional members intended the Fair Housing Act to achieve “truly integrated and balanced living patterns.”18 Lawmakers acknowledged that breaking down segregation was critical because “where a family lives, where it is allowed to live, is inextricably bound up with better education, better jobs, economic motivation, and good living conditions.”19 And some members of Congress specifically discussed new affordable housing in high-opportunity communities as one method of achieving open housing, with one stating “Title VIII will establish a ‘policy of dispersal through open housing… look[ing] into the eventual dissolution of the ghetto and the construction of low and moderate income housing in the suburbs.’”20 Court cases brought under the Fair Housing Act also help us understand the meaning of fair housing and the AFFH obligation. As one federal court has explained, the Act in general and the AFFH provision in particular reflect a congressional “desire to have HUD use its grant programs to assist in ending discrimination and segregation, to the point where the supply of genuinely open housing increases.”21 Another court held, “[a]ction must be taken to fulfill, as much as possible, the goal of open integrated residential housing patterns and to prevent the increase of segregation, in ghettos, of racial groups whose lack of opportunities the Act was designed to combat.”22 In one of the first cases interpreting the AFFH obligation, Shannon v. Department of Housing and Urban Development, the court found that HUD had an obligation to set procedures to determine how the location of a new subsidized housing project would impact racial concentration.23 The court acknowledged that in some cases efforts to revitalize areas of concentrated poverty may be the appropriate policy but concluded that “the agency’s judgment must be an informed one; one which weighs the alternatives and finds that the need for physical rehabilitation or additional minority housing at the site in question clearly outweighs the disadvantage of increasing or perpetuating racial concentration.”24 In another important fair housing case, the court made clear that land use measures that concentrate people of color in one area and exclude them from white neighborhoods violate the Fair Housing Act. In Town of Huntington, NY v. Huntington Branch, N.A.A.C.P, two black, lowincome residents and the NAACP sued the town of Huntington, a predominantly white suburb, over its zoning plan that confined all multifamily housing projects to certain “urban renewal” areas, where the majority of residents were African American.25 The Court of Appeals found the zoning plan had “a discriminatory impact because a disproportionately high percentage of 17 42 U.S.C. § 3608(e)(5). 114 Cong. Rec. 3422 (1968). 19 114 Cong. Rec. 2276, 2707 (1968). 20 NAACP, Boston Chapter v. HUD, 817 F.2d 149, 155 (1st Cir. 1987) (quoting Senator Proxmire). 21 Id. 22 Otero v. New York City Housing Authority, 484 F.2d 1122, 1134 (2d Cir. 1973). 23 Shannon v. HUD, 436 F.2d 809, 812 (3rd Cir. 1970). 24 Id. at 822. 25 Town of Huntington, NY v. Huntington Branch, N.A.A.C.P., 488 U.S. 15, 16 (1988). 18 5 households that use and that would be eligible for subsidized rental units are minorities, and because the ordinance restricts private construction of low-income housing to the largely minority urban renewal area, which ‘significantly perpetuated segregation in the Town.’”26 The Supreme Court agreed and struck down the zoning law as discriminatory. These cases, and many others, make clear that both HUD and local governments have an obligation to fight discrimination in housing and take steps to promote integrated neighborhoods that advance equitable access to opportunity. B. HUD’s AFFH Requirements and the Analysis of Impediments to Fair Housing Choice In the decades after enacting the Fair Housing Act, Congress reinforced the Act’s national mandate to incorporate fair housing goals into housing and community development programs by directly requiring recipients of HUD funds to certify that they will affirmatively further fair housing. For most recipients of HUD funds, including cities, counties, and states, this means they must prepare an Analysis of Impediments to Fair Housing Choice (AI).27 Under current law and regulations, the AI must include a comprehensive review of local laws, policies, and practices, in order to determine whether they restrict the availability of housing based on race, national origin, disability, or other groups protected from discrimination by the Fair Housing Act.28 The local government must then certify that it will take appropriate actions to overcome the effects of any impediments identified through that analysis. In the development of the AI, the local jurisdiction must include public participation of minorities and persons with disabilities. Ultimately, the AI is intended to help local governments do their part to combat restrictions on housing choice based on race, national origin, and disability, among others, and to promote open access to housing.29 However, through Democratic and Republican administrations, enforcement of these AFFH obligations has been weak, reflecting strong ongoing local resistance to residential integration. Since the adoption of the Fair Housing Act, for instance, HUD has only twice withheld money from jurisdictions for failing to meet their AFFH obligations.30 “[HUD’s] reluctance to enforce a law passed by both houses of Congress and repeatedly upheld by the courts reflects a larger political reality. Again and again, attempts to create integrated neighborhoods have foundered in the face of vehement opposition from homeowners.”31 The Obama administration has expressed a renewed commitment to making sure AIs are being done — and being done properly. In 2009, the U.S. Department of Justice and HUD intervened in a lawsuit against Westchester County, New York, in response to that County’s inadequate AI, resulting in a landmark affordable housing settlement. That settlement requires Westchester County to ensure the development of 750 new units of affordable housing in highopportunity communities that have few African American and Latino residents, and to affirmatively market those units outside the County in communities with large numbers of 26 Id. at 17. See, e.g., 24 CFR § 91.225(a)(1). 28 See generally, OFFICE OF FAIR HOUSING AND EQUAL OPPORTUNITY, DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT (HUD), THE FAIR HOUSING PLANNING GUIDE (1996). 29 Id. 30 Hannah-Jones, supra note 2. 31 Id. 27 6 residents of color.32 Because local governments control land use, Westchester committed to use all available means to achieve its obligations, including using litigation against cities and towns, if necessary.33 In addition to promoting new development, the County also committed to undertake a number of other actions to open up housing opportunities to families of color, including revision of its AI; fair housing outreach; and promotion of legislation to ban “source of income” discrimination. Shortly after the Westchester settlement was reached, HUD took enforcement actions in several other jurisdictions including the State of Texas and the County of Marin. And HUD announced that it would issue new AFFH regulations to provide communities with updated, clearer guidance about this obligation. Four years later we still have not seen those regulations. HUD has, however, provided some new guidance on AFFH — and insight into the Obama Administration’s vision of fair housing — through the direction it has given regarding fair housing obligations under a new program known as the Sustainable Community Regional Planning Grant program. (The Bay Area is a current recipient of one of these grants.) The fair housing obligations that HUD has set out for recipients under this program shed light on possible directions that may become requirements for all grantees should HUD issue its long-awaited new AFFH regulations. The core fair housing requirement placed on these grantees is to prepare a Regional Fair Housing and Equity Assessment (FHEA).34 This assessment must analyze patterns of residential segregation and disparities in opportunity across the region. It must explore demographic trends over time and what these demographics tell us about people’s access to opportunity — for instance, whether people of color primarily live in places with lower-performing schools, worse job access, or concentration of public housing. In particular, HUD has emphasized that the FHEA must take a close look at Racially Concentrated Areas of Poverty and what revitalization efforts are needed in those communities, such as economic development investments and park space.35 At the same time, the FHEA must analyze high-opportunity communities that are disproportionately white and ask what is contributing to that pattern, such as hostility by white homeowners and a lack of affordable housing.36 If HUD carries through with its renewed commitment to AFFH, and especially if it releases new AFFH regulations as expected in 2013, jurisdictions across the country are going to have to analyze, understand, and address their segregation patterns and disparities in opportunity. Getting it right will require the engagement and oversight of organized, strategic civil rights advocates and community leaders. V. Fair Housing in Marin County 32 Stipulation and Order of Settlement and Dismissal at 6-11, United States ex rel. Anti-Discrimination Center of Metro New York v. County of Westchester, No. 06 Civ. 2860 (S.D.N.Y. Aug. 2009). 33 Id. at 10. 34 OFFICE OF SUSTAINABLE HOUSING AND COMMUNITIES (OSHC), HUD, PROGRAM POLICY GUIDANCE OSHC-2012-03 (Feb. 17, 2012). 35 OSHC, HUD, REGIONAL FAIR HOUSING EQUITY ASSESSMENT: RACIALLY AND ETHNICALLY CONCENTRATED AREAS OF POVERTY (March 1, 2012). 36 OSHC, HUD, REGIONAL FAIR HOUSING EQUITY ASSESSMENT: DISPARITIES IN ACCESS TO OPPORTUNITY (March 12, 2012). 7 A. Segregation Patterns and Opportunity Disparities In the Bay Area, one can still see the remnants of the explicit racially discriminatory policies of the past, such as racial zoning, racially restrictive covenants, and steering, as well as the federal policies that facilitated white flight and created urban neighbors of concentrated poverty. Like many parts of the country, the segregation patterns created by these policies have been etched into the geography and are perpetuated by current policies and practices.37 For instance, you can see the stark racial segregation patterns of the Bay Area in the map below labeled “Residential Segregation Patterns of the Bay Area.” And the second map titled “2010 Racially Concentrated Areas of Poverty” shows the pockets of distressed neighborhoods that disproportionately home people of color. The maps below also highlight Marin County’s housing patterns that can be traced back to a long history of intentional racial segregation with a population than is significantly whiter than the region, and which lives in exclusive white communities, on the one hand, and pockets of racially concentrated poverty, on the other. Marin City, for instance, was first developed as a home for ship yard workers in the 1940s. Following World War II, white residents moved out of Marin City into private housing in other parts of the County while blacks were barred from living or buying homes in those areas.38 By the 1970s, Marin City’s population went from 10 percent African American to 75 percent African American. Long after the end of legal racial exclusion, these segregation patterns persist. Today, Marin City is nearly half African American, and, in general, the African American population of Marin is largely confined to just Marin City, Novato, and San Quentin Prison (which contains nearly 30 percent of the African Americans residing in the County, according to the census).39 Further, these segregation patterns represent significant differences in quality of life. As reported in the Portrait of Marin, in the American Human Development Index ranking, which measures health, education, and living standard, Marin City ranks number 43 out of a total of 48 tracts studied in Marin.40 Latino residents and lower-income Asian immigrants experience similar levels of isolation and poor health and social conditions in Marin. Almost half of Marin’s Latino residents live in the Canal Area, which is 76 percent Latino. The Canal is also home to a growing population of Asian immigrant families. Educational outcomes there are alarmingly low, with over half the adults lacking a high school diploma, and the typical work earns just $21,000, comparable to those earned in Arkansas and Mississippi.41 Across Marin, African American and Latino residents have much lower median household incomes, and are much likely to be living below the poverty level than white residents.42 This puts much of Marin’s ownership and rental housing out of reach for people of 37 See A. Golub, T. Sanchez and R. Marcantonio, Race, Space and Struggles for Mobility: Transportation Impacts on AfricanAmericans in Oakland and the East Bay, URBAN GEOGRAPHY (forthcoming, Spring 2013). 38 COUNTY OF MARIN, ANALYSIS OF IMPEDIMENTS TO FAIR HOUSING CHOICE Ch. 2, 9 (Oct. 2011). 39 SARAH BURD-SHARPS & KRISTEN LEWIS, A PORTRAIT OF MARIN: MARIN COUNTY HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2012 21(Jan. 2012). 40 Id. 41 Id. at 16, 44; see also ANALYSIS OF IMPEDIMENTS TO FAIR HOUSING CHOICE, supra note 37, at Ch 2, 8. 42 ;U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT (HUD), FINAL INVESTIGATIVE REPORT 59 (2009). 8 color. Far fewer than half of the African American and Latino families in Marin or any of the adjacent counties are able to afford an average market rate two-bedroom apartment in the County.43 This is why affordable housing in Marin disproportionately serves people of color. According to the latest County survey data on the percentage of people of color who live in affordable housing in Marin, compared to the county population as a whole, Latinos lived in affordable housing at more than twice the rate of their representation in the County population (13 percent), and African Americans at nearly four times the rate of their representation in the County population (2.9 percent). Whites – over 80 percent of general population – constituted about 50 percent of affordable housing residents. Because people of color are more likely to live in affordable housing, where that housing is built has a big impact on whether it alleviates or perpetuates segregation. Housing cost is not the only explanation for the stark segregation patterns in Marin, however. When we look at the census data to see what the racial composition of Marin would be if all households regardless of race or ethnicity could live where others at their income level live, it is clear that other factors limit housing opportunities for people of color. Only 57 percent of households in Marin would be white if there was no racial discrimination in the housing market. In actuality, Marin’s population is 82 percent white. This tells us that in addition to the need for affordable housing for lower-income families of color, Marin needs to provide open housing opportunities for higher-income people of color as well. B. Discriminatory Policies and Practices to Root Out While the legally-sanctioned racial policies of the past have been outlawed, other policies, practices, and conditions perpetuate these segregation patterns and disparities in opportunity. We must challenge individual acts of discrimination as well as County and city policies and practices that deny communities of color the investments they need and exclude protected groups from wealthier communities. Below is a list of the most often cited factors that perpetuate segregation in Marin: Landlords, real estate agents and brokers, and lenders continue to discriminate by treating people of color and immigrants differently, refusing to rent to them, steering them away from homes in white neighborhoods, and offering different loan terms. Recent tests for discrimination have also revealed differential treatment by landlords and agents of people with disabilities and families with children.44 Some people of color who can afford to buy a home in Marin choose not to because they feel the community is unwelcoming and hostile.45 Indeed, white residents of Marin have expressed strong NIMBY sentiments in debates over possible affordable housing development. Even worse, hateful racial and anti-immigrant messages have been made in response to fair housing education work in the County and other public conversations about community change.46 43 Id. at 60. Id. at Ch. 3, 10-28. 45 See id. Ch. 2, 9. 46 Id. at Ch. 3, 9-10. 44 9 Many people of color and immigrants cannot afford housing in affluent white towns. And exclusionary zoning policies in these towns make it difficult or impossible to build affordable multifamily housing. As the Analysis of Impediments found, “Limiting the development of affordable multifamily housing reduces housing options for those protected groups. Current zoning ordinances impose onerous restrictions on the development of high-density, multifamily housing, which limits the stock of available rental housing.”47 Affordable housing units, including Marin Housing Authority (MHA) developments, are concentrated in a few areas, primarily the Canal and Marin City.48 The Analysis of Impediments reports, “[a]lthough public housing applicants with families express the desire to live outside Marin City, there is no other family public housing in the county.”49 Similarly, Section 8 voucher holders, who are also mostly people of color, families with children, and disabled individuals, are disproportionately represented in areas with high concentrations of lower-income people of color, perpetuating segregation patterns. Areas of concentrated poverty and racial isolation need economic development investments, stronger infrastructure, and better services. Further, these investments must be made in a manner that benefits rather than displaces local residents. Limited public transportation also worsens segregation. “Public transportation resources are clustered in a few densely populated and more segregated communities, effectively perpetuating the concentration of minorities, women with children, and the disabled in certain neighborhoods.”50 There are housing limitations that particularly impact people with disabilities. For instance, “[t]he aging housing stock limits accessibility of units to people with disabilities, despite new construction’s compliance with contemporary building codes.”51 The factors that contribute to segregation and opportunity disparities in Marin will not disappear overnight. But with strategic, innovative advocacy supported by strong community engagement and a long-term vision for change they can be challenged. VI. Conclusion Housing has long been a focal point for racial tension in this country with white homeowners using public laws, private contracts, intimidation and violence, and any means they could find to keep African American families and other people of color out of their neighborhoods. For over 100 years, civil rights leaders and engaged community members have challenged this discrimination and exclusion with strategic campaigns. They have used organizing, advocacy, community-building, and litigation to demand equal access to housing and the neighborhoods of their choice. But this work is not done. We must tackle the policies that 47 Id. at i. Id. at ii; HUD FINAL INVESTIGATIVE REPORT, supra note 42, at 58-59. 49 ANALYSIS OF IMPEDIMENTS TO FAIR HOUSING CHOICE, supra note 37, at ii. 50 Id. at iii. 51 Id. at xi. 48 10 perpetuate discrimination and segregation in Marin, as well as the individual biases that underlie them. Like the civil rights struggles of the 20th century, this will require innovative policies, strategic advocacy campaigns, and an organized and engaged community base. We hope this background is helpful to ACE as it identifies priorities and strategizes how to seize the opportunities to push for reform and achieve equity in Marin. 11 12 13