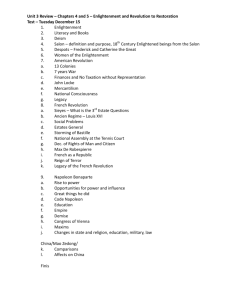

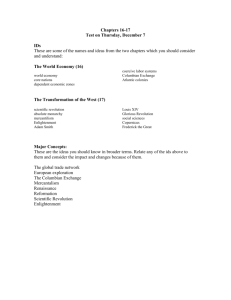

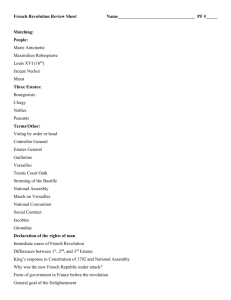

Chapter 2: Revolution and Enlightenment, 1600

advertisement