TC9/Pages (Page 1)

advertisement

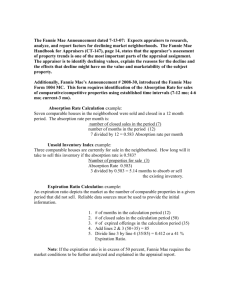

THE ART OF TAKING CHARGE THE HEIDRICK & STRUGGLES LEADERSHIP JOURNAL HOW JAMES A. JOHNSON AND FRANKLIN D. RAINES THE SUCCESSION AT MANAGED FANNIE MAE, ONE OF THE WORLD’S LARGEST FINANCIAL COMPANIES V O L U M E F O U R ■ N U M B E R O N E The Art of Taking Charge, The Heidrick & Struggles Leadership Journal, is published quarterly FLAWLESS TRANSITIONS for senior managers by Heidrick & Struggles International, Inc. Requests to be added to the mailing list or requests for reprints should be directed to the Client Service Department at 1-800-491-4849. THE ART OF TAKING CHARGE The Heidrick & Struggles Leadership Journal EDITOR Joel Kurtzman MANAGING EDITOR Jennifer Silver ART DIRECTION Ken Silvia Design Group The Art of Taking Charge (ISSN 10856617) is published quarterly by Heidrick & Struggles International, Inc., One Peachtree Center, Atlanta, GA 30308, www.heidrick.com. Copyright © 1999 Heidrick & Struggles International, Inc. No reproduction is permitted in Transitions are rarely flawless in the executive suite. Succession planning is often left to the last minute, and, since every company and corporate context is different, no one is ever really quite sure what constitutes best practices. For that reason, this issue of The Art of Taking Charge focuses on one of the most significant — and one of the smoothest — leadership transitions. It is the C.E.O. transition at Fannie Mae, one of the world’s largest and most important financial institutions. As this issue demonstrates, the transition at Fannie Mae actually took a year to implement. During that time, James A. Johnson, Fannie Mae’s chairman and chief executive, “reintroduced” his successor, Franklin D. Raines, to the organization he would take over. I say reintroduced because Mr. Raines, who was director of the Office of Management and Budget in the Clinton Administration when he was tapped by Mr. Johnson, had been a vice chairman of the company before that. What can we learn from the transition at Fannie Mae? I believe there are five major lessons. First, as a recent issue of the Harvard Business Review argues, you cannot have a smooth transition at the top if you bring in the wrong person. In some companies, the best person is already present, hard at work, in a job close to the top job. In other organizations, the right person must be sought from the outside. In either case, the new C.E.O.’s temperament, style and skills must fit the organization and the challenges it faces. I am not equating succession with cloning. Far from it. I am only stating that different organizations require different types of leaders. Second, it takes time to make succession work. Unless an organization is in crisis, boards should spend sufficient time getting to know their C.E.O.’s successor. In the case of Mr. Raines, the board knew him well because of his prior service with the company. But he was also well known to two of the firm’s main constituencies: to Wall Street, where Mr. Raines was a partner at Lazard Frères before coming to Washington, and to Congress, where he frequently testified. Third, even a well-known successor must be introduced into the company gradually. In the case of Fannie Mae, for several months after his selection but before he took office, Mr. Raines joined Mr. Johnson at Fannie Mae’s major internal meetings. In addition, Mr. Johnson gave Mr. Raines larger and larger tasks, culminating in the firm’s strategy-setting exercise. As a result, he was no stranger to the organization he now heads. Fourth, the successor must be introduced to the firm’s most important constituencies. In addition to Wall Street and Congress, Mr. Johnson and Mr. Raines conducted joint news conferences in the United States and abroad and met with key business partners around the world. Fifth, the people who were passed over for the top job must understand that they still have value. When an outsider is brought in, the new leader should take the opportunity to interact with the people in the organization who were passed over in order to avoid creating an exodus of talent. No transition is ever perfect. But so far the change at the top at Fannie Mae appears to be about as good as they get. I hope you enjoy this issue of The Art of Taking Charge. whole or part without the express consent of Heidrick & Struggles International, Inc. Postmaster: send changes to Sincerely, P.O. Box 9340, Boston, MA 02209-9340. PATRICK S. PITTARD President and Chief Executive Officer Heidrick & Struggles International, Inc. Photos by Anthony Loew MANAGING SUCCESSION AT THE TOP An exclusive conversation with James A. Johnson, former chairman and chief executive officer, and Franklin D. Raines, chairman and chief executive officer, of Fannie Mae F annie Mae — once more stodgily known as the Federal National Mortgage Association — was chartered by Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1938 during one of the darkest periods of the Great Depression. But with its singular and popular mission of making housing affordable for low- and middle-income borrowers, it not only survived those bleak years but prospered, transforming itself in 1968 from a government agency into a private corporation with publicly traded stock that has soared over the last 10 years. With the growth in its primary business — buying and securitizing single-family home mortgages originated by other lending institutions — Fannie Mae has become one of the largest and most powerful financial institutions in the United States. Its assets totaled just over $500 billion at the end of the first quarter this year. And over the last three decades, it has provided more than $2.6 trillion in homeowner financing. Even more impressive, it hopes to provide a full $1 trillion more in the few short years from 1994 through the end of 2000. Just three years after James A. Johnson took charge as Fannie Mae’s chairman and chief executive, he challenged the company to provide $1 trillion in new mortgages to 10 million low- and middleincome borrowers within just seven years — and, with $700 billion lent as of the end of last year to 8.3 million families, that goal looks to be well within reach. In its growth and transformation, Fannie Mae offers an enlightening study of leadership on several levels. Besides its financial goals, the company illustrates the power that comes from recognizing diversity as an asset in the workplace; one of its biggest goals, and successes, has been to increase the number of minorities in its work force and on its board. Furthermore, the Fannie Mae experience demonstrates the importance of selecting executives whose backgrounds fit the unique circumstances of the organizations they will lead. In the case of Fannie Mae, with its Washington headquarters and links to the Government as well as to the world’s financial markets, only an executive with facility across the spectrum of finance, management, business and politics can truly take charge. Both James A. Johnson, 56, and Franklin D. Raines, 51, have been so blessed. From his first dealings with Fannie Mae, Mr. Johnson demonstrated a wealth of political acumen. The son of a politician — his father was speaker of the Minnesota State House — Mr. Johnson was elected president of the student body at the University of Minnesota and vice president of the National Student Association. He received his masters in public administration from Princeton University after which he went to work for Dayton Hudson as director of government and public affairs. Mr. Johnson then garnered even more political savvy when he became a top aid to Vice President Walter F. Mondale in the 1970’s. After the Carter-Mondale ticket was defeated in 1980, he set up a Washington-based consulting firm, Public Strategies. And when that firm was sold to Shearson Lehman Brothers in 1985, Mr. Johnson and his partners became managing T HE ART OF TAKING CHARGE 1 directors, and Fannie Mae became one of Mr. Johnson’s clients. Having built what he calls “a very solid background in the company,” Mr. Johnson agreed to join Fannie Mae in 1989 and was elected its vice chairman. Thirteen months later, after a transition that served as a prototype for the current handoff, Mr. Johnson succeeded David Maxwell as Fannie Mae’s chairman and chief executive. Last year, it became Franklin Raines’ turn. Chosen by the board to become the new chairman and chief executive when Mr. Johnson stepped down at the start of 1999, Mr. Raines has shown himself to be no less impressive than his predecessor in ably straddling Wall Street and Washington. Raised in Seattle, Mr. Raines rose from poverty to earn a law degree from Harvard and become a Rhodes Scholar. After Harvard, he worked as an assistant director of the White House domestic policy staff during the Carter Administration, and then he joined Lazard Frères, the New York investment bank, where he specialized in municipal finance. Mr. Raines left Lazard at the end of 1990, and in 1991 Mr. Johnson lured him to Fannie Mae with the post of vice chairman. Five years later, he joined the Clinton Administration as director of the Office of Management and Budget, a Cabinet-level position. Two years after that, he rejoined Mr. Johnson as his designated successor. The transition from Mr. Johnson to Mr. Raines has gone so smoothly not simply because both men worked so closely together at Fannie Mae in the first part of the decade but also because Mr. Johnson involved Mr. Raines in the current process early on. It was Mr. Raines’ responsibility, for instance, to develop the 1999 business plan. As part of the transition, the two men traveled together to meet with Fannie Mae’s customers, visit its regional offices, talk to its employees, canvass Wall Street and sit down with partners in Asia and Europe. Together they took the opportunity — “a powerful opportunity,” Mr. Johnson called it — to inform the nation’s major newspapers and magazines of their transition and mission. Equally important to the orderly transition is the fact that Mr. Johnson is staying on the board through the end of the year to help wherever he can. So how do you deftly manage such a delicate maneuver as succession at one of the nation’s largest financial 2 institutions? What follows is a conversation on that question between Mr. Johnson, Mr. Raines and Joel Kurtzman, editor of The Art of Taking Charge, at the Fannie Mae offices in Washington. JK: Transition is a tricky topic for many companies. Yet Fannie Mae has confronted it head-on and you two are perfecting a process that could — perhaps, should — become a model for companies that balk at the challenge. You already had the example of David Maxwell passing the baton to Jim in 1991 in a very orderly and measured fashion. So how did you prepare for this transition, and what is left to do? MR. JOHNSON: It’s actually about 90 percent over now, and all has gone very smoothly. As planned, Frank took over from me as chairman and chief executive on Jan. 1. And I’m going to be around for the rest of this year, helping him out. But that is, at most, 10 to 15 percent of the story. The real story of the transition revolves around selecting Frank and reintroducing him into the company. He was my vice chairman from 1991 through 1996 but he needed some lead time to get reacquainted with the company after serving on the President’s Cabinet as director of the Office of Management and Budget. So he rejoined Fannie Mae last spring as my designated successor, and from that point through December we essentially worked in partnership. I was still the C.E.O., but we worked together to position the change that was needed. That way, when Frank took over, he was fully prepared to accelerate the momentum of the company instead of lose momentum, which would have happened if he had had to wait until he actually became the top guy to start looking at people, studying issues, creating task forces, undoing what I had done, undoing my budget, my business plan, my investment plan. All of those things were done, but cooperatively, with Frank taking the lead on all of the dimensions of the ‘99 business plan, budget and investment plan. Then, when he took over, he was taking over a company that was already his. And that’s what I think is so unusual about the Fannie Mae approach. MR. RAINES: In reality, the biggest thing that happened when I took over was the moving of the furniture from one office to the other — I moved into Jim’s office and he moved into mine. So, literally, for our people, there was only this symbolic changing of place to represent the change in responsibility. The organization was not thrown into any upheaval because of the new guard; it didn’t have to stop and figure out where to go from that point. MR. JOHNSON: On Frank’s first day, I think that most people in the organization felt they were pretty much done with the changeover to the new C.E.O., as opposed to just starting it, with all the fear and anxiety that usually accompany this kind of change. JK: Still, despite all your preparation, there must have been some surprises? MR. JOHNSON: I’d add one thing to the surprise list that is material to what happened during the transition, and that is that from August through November last year we had the biggest strain ever for us in our financial markets. Virtually every part of the real estate industry was fundamentally repriced in the market, and we had a dramatic and unprecedented set of challenges as a company. We took $10 billion from our liquidity portfolio and reoriented our capital to take care of new mortgage growth. We had huge international capital flows from Asia and Europe that were coming off of the Russian collapse in August, and that required an unusual level of corporate response, which we managed. All of this underscored the vital role our company plays. But this huge market dislocation happened in the midst of the transition, and it became an unexpected learning experience for all of us going through the transition. “The transition period MR. RAINES: The only surprise to me was how many bases there were that had to be touched in the transition. So many people had a stake in understanding the change, all over the world. By the time we were finished, we’d done a lot of traveling, met a lot of people, made a lot of contacts. And if you had asked me how intense that part of it would have been, I would have way underestimated it. I think, at least from my standpoint, the transition played out the way Jim and I said it would. Of course, we had an advantage there, since how it would work was basically up to the two of us. But I can’t think of another surprise. Since I took over, I can’t think of anything where I would now say . . . itself gives the company an MR. JOHNSON: . . .if only I’d known? for the company”— MR. RAINES: Yes, if only I’d known such and such, boy, would this have been better. extraordinary opportunity to invite focus. Now, if your transition in leadership is a mess, the focus is all counterproductive. If your transition, however, is well-organized and wellexecuted, it’s a huge asset Mr. Johnson JK: Frank, you mentioned the enormous amount of base-touching you had to do in the transition. How much of it did the two of you do together? MR. RAINES: Basically, all of it. MR. JOHNSON: We did all the customers. We did all the regional offices. We did all the employees. We did Asia. We did Europe. We did Wall Street. Over one twoweek period, Frank and I together met with the editors of The Washington Post, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, Forbes, Fortune, the American Banker and USA Today, plus a couple of others. We did every one of them together. We said, here’s who we are, here’s what we’ve been T HE ART OF TAKING CHARGE 3 doing, here’s where we’re going. The transition period itself gives the company an extraordinary opportunity to invite focus. Now, if your transition in leadership is a mess, the focus is all counterproductive. If your transition, however, is well-organized and well-executed, it’s a huge asset for the company. Every one of those meetings provided us with a powerful opportunity to make important people aware of our mission and goals and our new leadership. said, we’ve done a lot of work in passing on both my relationships and institutional ones, but if there’s somebody who is vital to the company, whether it be a customer or head of a Wall Street firm or a Congressman, who happens to be a friend of mine, Frank can just pick up the phone and say, “Jim, by the way, would you go see Hank Paulson now that he’s the head of Goldman, Sachs. I know he’s a friend of yours, and we’d like to talk something over with him.” And I’m here to do it, without hesitation. JK: How about on the political side? JK: So what can other companies learn from your transition process? MR. JOHNSON: Same thing. We did an enormous amount of political work here in Washington. For one thing, we had multiple going-away events attended by many members of Congress and the Administration. MR. RAINES: I think too many companies believe that all they need to do for succession is to pick a person. They say, we’ve decided, that’s done — and they start trying to run the company with the new regime. But they wouldn’t do anything else in the company like that. They treat this unlike they treat anything else. They don’t manage it, they don’t plan for it, they don’t focus on execution, they don’t evaluate how it is going. MR. RAINES: To illustrate the high-level of interest we generated, the principal speakers at one going-away event I hosted for Jim were Treasury Secretary Bob Rubin and Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan and Commerce Secretary Bill Daley. Colin Powell was there. Everybody in Washington was there. But it’s very clear two things were important. One, they all wanted to be there OMMITMENT TO INORITIES to honor Jim. And, secondly, they weren’t Percentage of Fannie Mae employees who are minorities, strangers to me either. It wasn’t as though at the end of each year. they had to start getting to know this new PERCENT person and figuring out how to deal with 45 him and wondering how he would deal 40 with them. AC I already knew many of these people and, for those I didn’t, Jim has been able to do many of the introductions. It’s very unusual in a transition to have someone be able to pass on such important relationships with such ease. In most places, the relationships dissolve with the departing executive, and the new guy has to go out and recreate them or create new ones. MR. JOHNSON: That’s part of the importance of my staying on in ’99. As Frank 4 THE HEIDRICK & STRUGGLES LEADERSHIP J OURNAL 35 M Fannie Mae work force 30 25 20 15 10 Fannie Mae officers and directors 5 0 1987 ’88 ’89 ’90 ’91 ’92 ’93 ’94 ’95 ’96 ’97 ’98 MR. JOHNSON: Basically, they don’t position themselves in advance. JK: There are probably more examples of sudden transitions than there are examples of smooth transitions like the one you two have achieved together. What is the difference? Is it institutional? Does it depend on personalities? On the singularity of mission? MR. RAINES: Like most things, it’s something that is learned. I think the fact that David Maxwell put so much effort into the transition from himself to Jim laid the seeds for Jim to put that kind of effort into the process this time. MR. JOHNSON: I started thinking about it virtually from the time I became C.E.O. When I chose Frank as vice chairman in 1991, part of what was on my mind was the question: Am I getting someone here who might ultimately be positioned well to succeed me by virtue of capability and age and such? And, it turned out, I was. JK: So why is it other institutions can’t master this? MR. RAINES: It’s a question of how much value you put on a successful transition. If you don’t value it very highly, you’re not going to do it very well. MR. JOHNSON: And how much priority you put on a coherent strategy and a clear set of values so that you know what it is you’re passing on. MR. RAINES: If you’re going to have a successful transition, you first have to decide you’re going to have a transition; then you have to plan for it, and, finally, execute it. In many cases, companies don’t confront, or the leaders don’t confront, that a transition is about to happen. So, by denying it, they never get around to planning for it. They may ask any number of managers how they plan to replace this one or that one, but they never ask the C.E.O. for a succession plan. Or if they do, they seldom take it beyond that, never confronting how they are going to get smoothly from a designated successor to the point where that person is actually sitting, comfortably, in the chair. JK: What role does the board play here? MR. JOHNSON: In our case, a very substantial one. I started talking with our board three years ago about the transition process. We didn’t discuss the exact timing of any of it, but I had said from the beginning that I would not stay for more than 10 years, and my 10 years will be up at the end of ‘99. When it came time to actually look at successors, the key directors were very active in considering all potential candidates. We had a number of candidates, in fact, but there was an immediate coalescence on Frank. So, with the board’s approval, I went to Frank, and my timing and his timing meshed, so we went forward and his selection was approved at our April meeting last year. I always had in my mind that I might have a sort of postC.E.O. period of at least a few months, but that worked best into a full year — and still we are within six months of our original timetable on this. JK: Jim, you said you started thinking about how to arrange for your successor almost from the moment you took over the company nearly 10 years ago. Can you describe more specifically how you were influenced in this process by your transition to the chairmanship and C.E.O. post under David Maxwell, and how that transition helped you to take charge? MR. JOHNSON: That was a very successful experience. I had already worked for three and a half years as an outside adviser to the company while I was a partner at Lehman Brothers, and in that time I learned both the financial challenges as well as the culture that had been created by David. So I had a very solid background in the company when he asked me to join and the board elected me vice chairman in 1989. I then had 13 months in that job before I became the C.E.O., including a five-month overlap with David after I’d been designated to be the new C.E.O. This allowed me to do a very thorough assessment of the public responsibilities of the company plus a very thorough assessment of its business strategies, since I had worked on significant dimensions of those strategies at Lehman Brothers. It also allowed me to get to know the people very well. T HE ART OF TAKING CHARGE 5 qualitative goals, in terms of our contribution to solving Once I actually took over, I was well-prepared and ready housing problems and our contribution to building a quality to lead right away. I actually felt comfortable enough to work force. There are also some quantitative dimensions move quickly on my agenda and in my own style. For within those goals. instance, I have a very strong predisposition to large, publicly stated goals, so over the course of my initial months as JK: What more specifically would some C.E.O. I made a number of big commitof the qualitative goals be? ments — to Wall Street, for example, R EACHING HIGH that we would deliver a double-digit How Fannie Mae has fared MR. JOHNSON: One is to be a worldannual earnings increase, and to the in meeting the goals it set in 1994 class example of diversity. And this isn’t for the end of the year 2000. housing community that we would do numbers-driven for us. It means creat$10 billion of targeted lending in cateGOAL: Providing $1 …to help finance ing an overall corporate environment trillion in targeted homes for 10 gories where, at that time, we only had mortgage financing… million families. that clearly commits the corporation to about $200 million of that kind of lend$TRILLIONS MILLIONS OF FAMILIES diversity, to encouraging a work atmosing on our books. 1.0 10 phere that values people of all kinds. It I believe very strongly in the power also involves corporate justice, so that of publicly articulated strategic goals. I .8 8 there are avenues for remedying probthink it allows the organization to pull lems when people feel you’re not living together because it gives people in the .6 6 up to the principles you’ve embraced. company a sense of excitement, a sense Our quantitative numbers here are of having a higher mission. People may .4 4 strong, but becoming a world-class be motivated significantly by money, example of diversity is as much a qualibut that is never the whole story. .2 2 tative challenge as it is quantitative. We’re pleased to have been designated JK: How then did you determine 0 0 by Fortune magazine as one of the best whether or not you were accomplishing Achievement through Goal for end of places for minorities to work. those goals? end of 1998 year 2000 Another of our qualitative goals is to broaden homeownership to people who MR. JOHNSON: All of the goals we set have previously not been able to own their own homes. We had numerical, quantitative dimensions. The biggest quantibelieve that lack of information is a huge barrier here. tative goal we ever set was in ’94, when we said we would People are too often uncomfortable with financial instituprovide $1 trillion in targeted mortgage financing by the tions, uncomfortable with the words that are used and the end of the year 2000 to help finance homes for 10 million terms of the mortgage process, with escrow accounts and low- and middle-income families. We’re well on our way to points and title searches. There are more people than you meeting this goal. On the qualitative side, there were 11 think who believe that, even though they hold a steady job, dimensions of transformation. they would not qualify for a mortgage. In our goal setting, in fact, we have tried to be a leader in And there are 33 million Americans for whom English is measuring qualitative goals. We recognize that, with very few not their first language. So, through the Fannie Mae exceptions, there are not only long- and short-term dimenFoundation, we created a television, print and radio outreach sions to goals, but also qualitative as well as quantitative program where we are trying to invite these people into a diadimensions. And so, for example, in our incentive program, logue with us to teach them how to pursue homeownership. 50 percent of our long-term pay at Fannie Mae rests on what We’ve actually had six and a half million families call us on we call the report card, and the report card is a series of 6 THE HEIDRICK & STRUGGLES LEADERSHIP J OURNAL the phone in response to our advertising. And we’ve sent them information — in Spanish or Chinese or Korean or Portuguese or Polish or Russian or whatever — and then have invited them to call back if they’d like further counseling. Now, some of this is quantitative, too. For example, we sponsor 12 teams in the National Basketball Association because the people we’re after watch the N.B.A. games. And since we make it sort of a condition of our sponsorship that the team will get behind the revival of urban neighborhoods, we’ve had a lot of the players themselves out working with us, actually pounding nails and doing real work. JK: So you’re obviously working hard and apparently faring well at communicating your message to the outside world — but what about internally? Many C.E.O.’s are frustrated by the fact that, hard as it may be to fashion their goals and strategy, it is harder still to get them embedded in the culture and to inspire people to work toward them. MR. JOHNSON: We are so fortunate in that regard. In our latest company survey, 91 percent of our employees said they fully understood and embraced the core strategy of this company. MR. RAINES: I think that number is so high because, for one, we have only 4,000 employees. That’s a big advantage in being able to communicate fairly easily with everyone. In addition, our work is something that is very tangible, very visible and very rewarding on several levels. Our people not only see results numerically, but every day they understand that by virtue of what they do, other people are fulfilling the No. 1 aspiration in their life, which is to own their own home. And that is very fulfilling on a personal level to the people who helped make that happen. What’s involved here is a whole theory of corporate and communication strategies. Very often people have trouble communicat- ing a mission or strategy because they don’t really have one. But more important than having any mission, I think, is to have one that is beyond the product or service of the day. Our corporate mission is homeownership and that transcends how we are doing our job today. It is something people can understand, which frees them to think of it broadly and innovatively. It’s not a strategy that is owned by senior management, that only senior management can articulate. It’s a strategy that every one of our people can embrace and encourage because they can identify with it. Everything for us goes back to homeownership. And when you have such a strong, shared purpose, you can communicate more easily with people. JK: It’s interesting to note that that mission has stayed the same throughout some considerable changes Fannie Mae has undergone since it was created as a Government entity in 1938. More recently, over more or less the past two decades, the business has truly been transformed by the securitization of mortgages and financial innovations affecting your market. How do you lead and communicate, both inside and outside the organization, amid such change? “Very often people have trouble communicating a mission or strategy because they don’t really have one. But more important than having any mission, I think, is to have one that is beyond the product or service of the day.” —Mr.Raines T HE ART OF TAKING CHARGE 7 MR. RAINES: The company has definitely changed dramatically from when Jim’s predecessor came in here in terms of how we do the business, the ingredients to the business, our mix of people – there’s been a huge change. MR. JOHNSON: And it was only 30 years ago that we became a totally privately owned institution. Then we got into the mortgage-backed securities business and into other dimensions of the mortgage market. And so, even before the last 20 years, where we’ve had huge change, we were transforming ourselves repeatedly. MR. RAINES: But I think the change with the biggest impact on how we lead has been the change in the skills of the people we need to attract to meet each new challenge. As these skills change, the culture of the workplace changes, and management must adjust how it goes about communicating and implementing strategy depending on that new culture. When Jim became chairman, for example, probably 10 percent of our employees were technology people and probably 30 to 40 percent were operations people who had been doing a lot of manual things to make the business happen. Today, a third of our employees are technology people, and the operations side is probably closer to 10 percent. That’s a huge change in skill sets. And the technology people obviously have their own culture and way they think about things and how they like to interact — so that now, for instance, we have the intranet as a major means of communication, instead of the operating memo. 8 THE HEIDRICK & STRUGGLES LEADERSHIP J OURNAL Still, as you said, our overall mission has remained the same across all these big changes and, from a corporate standpoint, that’s the hardest thing to do. Usually what happens is you have an enduring bureaucracy and a changing mission; we’ve really had an enduring mission while the bureaucracy has changed. JK: Has all this change required a different type of leader? “ If you’re going to have a successful transition, you first have to decide you’re going to have a transition; then you have to plan for it, and, finally, execute it .” —Mr.Raines MR. JOHNSON: Well, the fact that Frank is more technologically capable and informed and experienced than I am is, I have no doubt, going to be a tremendous asset for him and the company. Now, could Frank have been a great C.E.O. choice without that? Yes. But his expertise will definitely be an asset as the technology of mortgage finance continues to change. So, yes, David had strengths, I had strengths, Frank has strengths, and they become vital at different times, in different ways. But certainly on this big dimension of tech- nological change, the fact that Frank is a technology strategist is an enormous asset as he comes into this. MR. RAINES: And I think an innovation that Jim brought about when he took over was very important in the recent evolution of the company. When David was chairman he had five presidents, and he was struggling to get the leadership formula right until he landed on one, Roger Birk, where the fit was finally good. In his turn, Jim then asked By setting up the office of the chairman, therefore, I think we reduced our risk on the leadership side by expanding our definition of leader. JK: In essence, then, you have a team approach. But let’s discuss that a little more fully. I have interviewed C.E.O.’s who adamantly reject teams, insisting that one person must be accountable, even if there are five others working with him. Others would say a team is responsible for its actions and that results should be evaluated based on the whole team. “When I chose Frank as vice chairman in 1991, part of what was on my mind was the question: Am I getting someone here who might ultimately be positioned well to succeed me by virtue of capability and age and such? And, it turned out, I was.” why we were stuck with just a chairman and president in terms of the mix of leadership skills, and so he created an office of the chairman that consists of the chairman, president and the vice chairman. Each of them has a different interest and focus within the organization, which greatly increases the likelihood you will get the leadership right. More important, you can actually work on three things at the same time; it’s a high-risk bet to put everything on the shoulders of just one person. MR. RAINES: You can have a team and still have someone responsible for ensuring that the team is on the field, with all players going on with the same plays, all working together. There has never been any doubt here about who the C.E.O. was, no doubt at all. But that doesn’t mean the C.E.O. is a lone actor. JK: So teams can have captains, in other words? MR. RAINES: Teams can have captains, teams can have managers. Problems arise, I think, when a manager asserts: I’m in —Mr. Johnson charge, leave me alone, I’ll come back at the end and tell you what happened. At the other extreme are teams where the members say: We’re all in charge. I think our approach has been much more one in which someone takes the lead on a project but we’re all in close communication on it, and when an important decision looms, we’ve got a C.E.O. who can make that decision. But it doesn’t mean the C.E.O. has to go out and actually take the lead on everything that the company is trying to do, nor does it mean the C.E.O. has only a binary choice on leadership: T HE ART OF TAKING CHARGE 9 Now, I must add that there’s also a dimension of tough grading in all of this, whether you’re assessing your own performance or that of others. Organizations have different standards of excellence, but part of what we’ve tried to do — and David Maxwell is really the father of this — is to introduce and reinforce a management culture of being the best and of performing the best analysis, the best research, the best customer service. And we’re continually pushing ourselves to achieve that excellence. Either I do it myself or I give it up entirely to someone else. I can’t remember any issue where Jim said, O.K., you handle this and I don’t want to see it again. On the other hand, there have been a ton of issues where he said, all right, you’ve got the lead on that one, keep me in the loop. It becomes very much a collaborative process. JK: It sounds very collegial. MR. JOHNSON: It is very collegial. And I think Frank and I think the same about the way to handle a very large number of things in the context of collegiality. For instance, I spent most of my time as C.E.O. engaged in what I would call high-level scanning of issues and scanning of the horizon. And one of the things I did as part of that was to set aside four hours every Monday morning to hear from a total of about 35 people, face to face, on what they were doing, what they were working on and what they were worried about. My input was really minimal. I might point out a recent article in The Wall Street Journal that bore on an issue we were discussing, or mention a pertinent talk with Senator So-and-so. What was really important was what I heard from everybody involved. More than anything else, my management style was to try to get individuals or teams of individuals handling virtually everything. Then I could continually scan to see whether $90 or not I thought that they were prop80 erly aligned with the overall corporate 70 strategy; and if I decided somebody was off course, then I would get directly involved in getting them back on course. 60 JK: In those instances, were you the one that determined when to get involved? 30 MR. JOHNSON: Yes. And I think that’s a very useful power for the C.E.O. to retain. 0 1987 ’88 10 JK: Is it something you measure? MR. JOHNSON: Yes, in dozens of different ways. We do all kinds of customer surveys, we do employee surveys and we do supplier surveys. And we have lots of internal feedback arrangements and external feedback arrangements. MR. RAINES: The only thing I’d add is that there’s also a push to have a sense of urgency. In any company, there’s always a tendency to want to be careful, to take your time, to not do anything until it’s totally had a chance to percolate and everybody’s had a chance to look at it. But that can be death for a company trying to be innovative. And so main- SOARING VALUES Fannie Mae’s yearend stock price 50 40 20 10 ’89 *Through April THE HEIDRICK & S TRUGGLES LEADERSHIP JOURNAL ’90 ’91 ’92 ’93 ’94 ’95 ’96 ’97 ’98 ’99* taining a sense of urgency as the company’s gotten bigger and more successful has been an important part of our leadership process. JK: One measure of that success has been your stock price, which is now trading for many times what it fetched in 1990. You mentioned earlier several forces that motivate your people, but what about stock ownership? How much of a stake do your employees have in Fannie Mae? MR. RAINES: Almost every employee has some stock participation in the company. And members of the board also have an ownership stake; most of their compensation, in fact, comes from stock options. So everybody involved in the company has a financial stake in it. JK: So would you say the company is particularly focused on shareholder value issues? MR. RAINES: I think that everybody, including the board, is very focused on our mission. We have a fundamental belief that if we do this mission right, the shareholder value will be just fine. If we get the mission wrong, there’s nothing we can do to overcome that for the shareholder. We can’t perform for the shareholder without also getting the mission right. So H&S for everyone involved, we must get the mission right. THE ART OF TAKING C HARGE 11 Heidrick & Struggles International, Inc., is one of the world’s leading executive search firms, operating in major business centers throughout North America, Europe, Latin America, Asia Pacific, Africa and the Middle East. The firm’s consultants help public and private corporations and not-for-profit organizations build high-performance leadership teams. Visit our web site at: www.heidrick.com ABOUT THE EDITOR The Art of Taking Charge is edited by Joel Kurtzman, former executive editor of the Harvard Business Review and former business columnist at The New York Times. Mr. Kurtzman, an economist and international business consultant, is the author of 14 books and numerous articles that have appeared in newspapers and magazines around the world. He has testified before the U.S. House of Representatives as well as the General Assembly of the United Nations on economic matters. Mr. Kurtzman has lectured widely, at Columbia, Georgetown, Harvard and Oxford universities, at the Keidanren, Tokyo, and at many companies. He was the host of the PBS TV special “Four Weeks in the Life of the Global Economy.” In Japan, he was host of “The Death of Money!” an NHK TV special. He has also hosted “Hodotokushyu,” the Japanese equivalent of “60 Minutes.” Mr. Kurtzman appears frequently on CNN. HEIDRICK & STRUGGLES O f f i c e s i n P r i n c i p a l C i t i e s PRINTED IN CANADA o f t h e Wo r l d