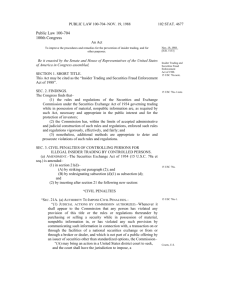

the genesis of an ethical imperative: the sec in transition

advertisement