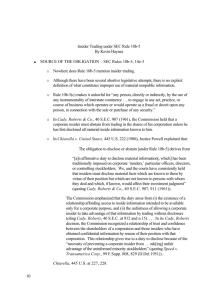

Insider Trading Liability for Tippers and Tippees

advertisement