13 The Non-Breach Position: Proving What Would

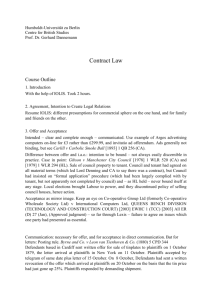

advertisement